Pewee Valley First Baptist Church & Colored School

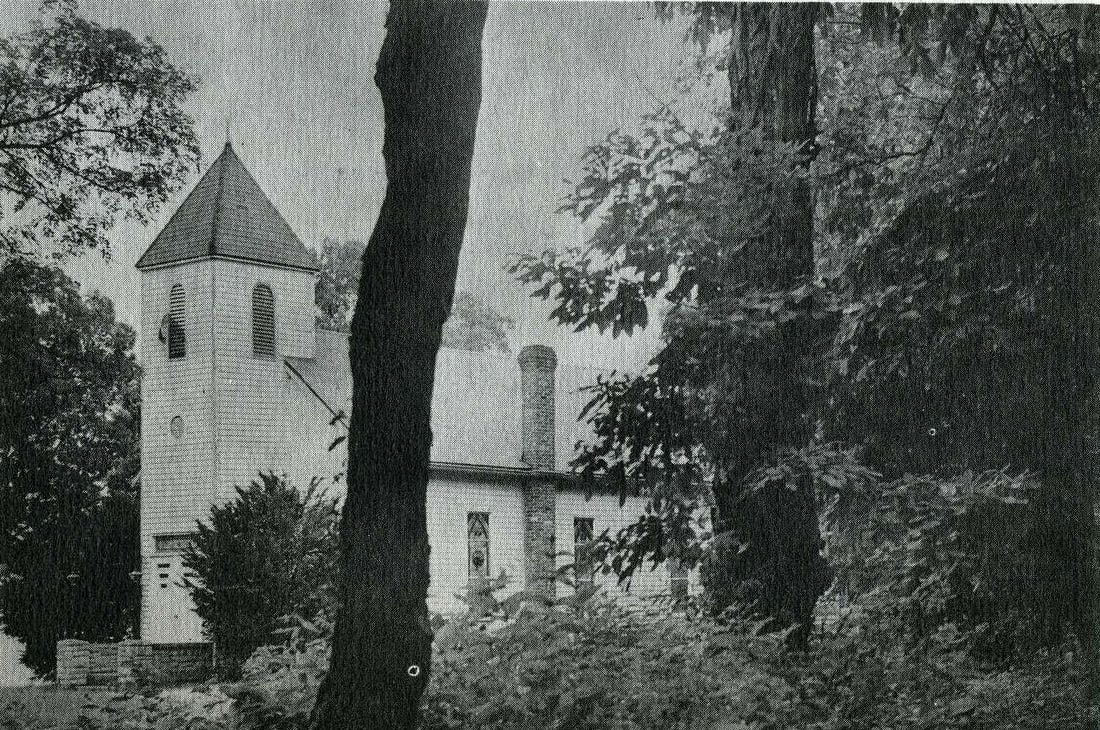

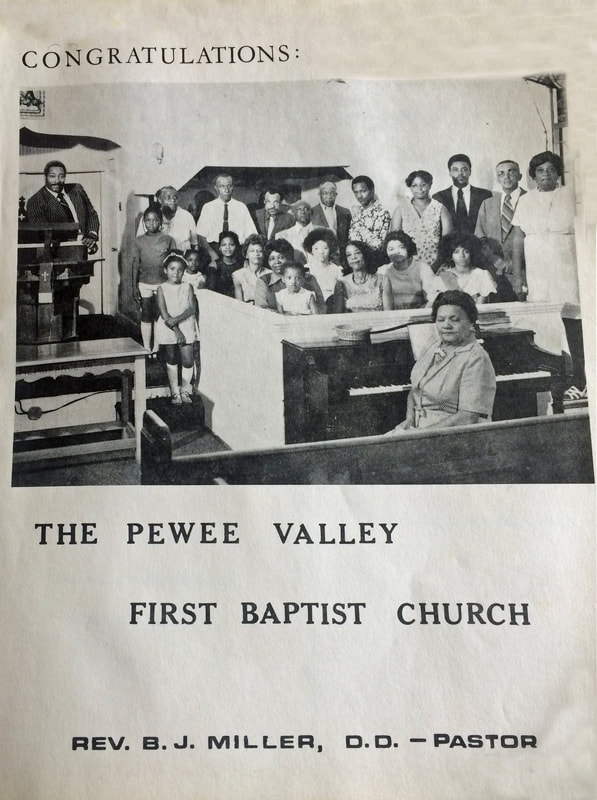

The Pewee Valley First Baptist Church, located at 7104 Old Floydsburg Road, is the oldest of two African-American churches in the area. The other, Sycamore Chapel, is located in Frazier Town.

According to "History & Families of Oldham County, Kentucky: The First Century 1824-1924," published by the Oldham County Historical Society (Turner Publishing, Paducah, Ky.; 1996), p. 260, Pewee Valley First Baptist Church was originally established by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Unclaimed Lands of Kentucky -- a.k.a. the "Freedmen's Bureau" -- as a combination school and church:

... the Freedman's Bureau of Kentucky assisted former slaves in the erection of a crudely constructed building to serve as a church on Sunday and as a school during the week. Men of the congregation worked diligently to clear the wooded plot. Utilizing the felled timber, they hewed tables and pews to finish the church building ...

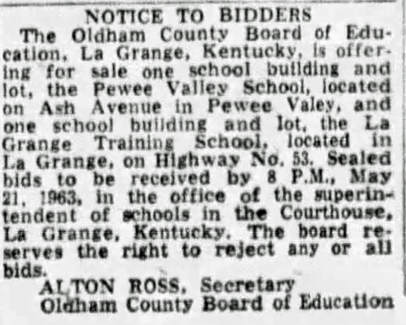

It was the second of two schools the Freedmen's Bureau established in Oldham County during the agency's brief tenure in Kentucky. The first, in LaGrange, was built in 1867, and was one of eight such schools erected in the commonwealth that year. The LaGrange school was built of wood and measured 16- by 20-feet, according to the "Fourth Semi-Annual Report on Schools and Finances of Freedman," published by the bureau on July 1, 1867. That same year, schools were also built in Bardstown, Mt. Sterling, Versailles, Frankfort, Washington, Bowling Green, and Owensboro.

Erected two years later in 1869, Pewee Valley's school cost $292.50 to construct. The land on which it was built was leased for 99 years from the church, according to the "Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Unclaimed Lands Eighth Semi-Annual Report." Other schools were also established that year in Cloverport, Shelbyville, Lebanon and Berea.

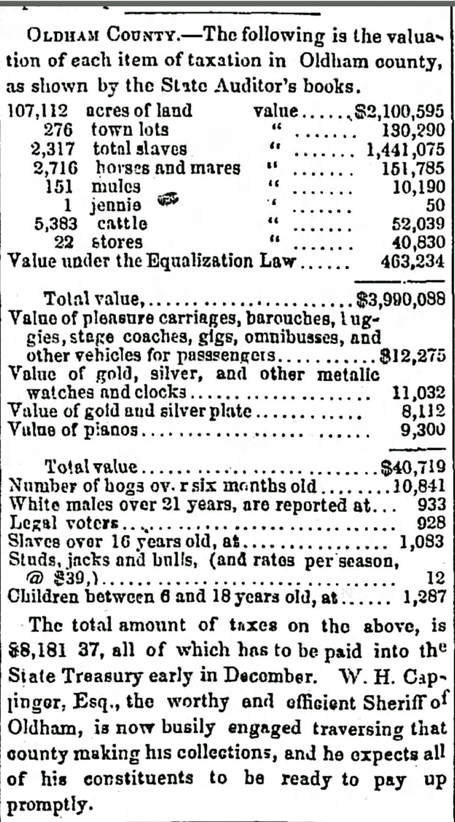

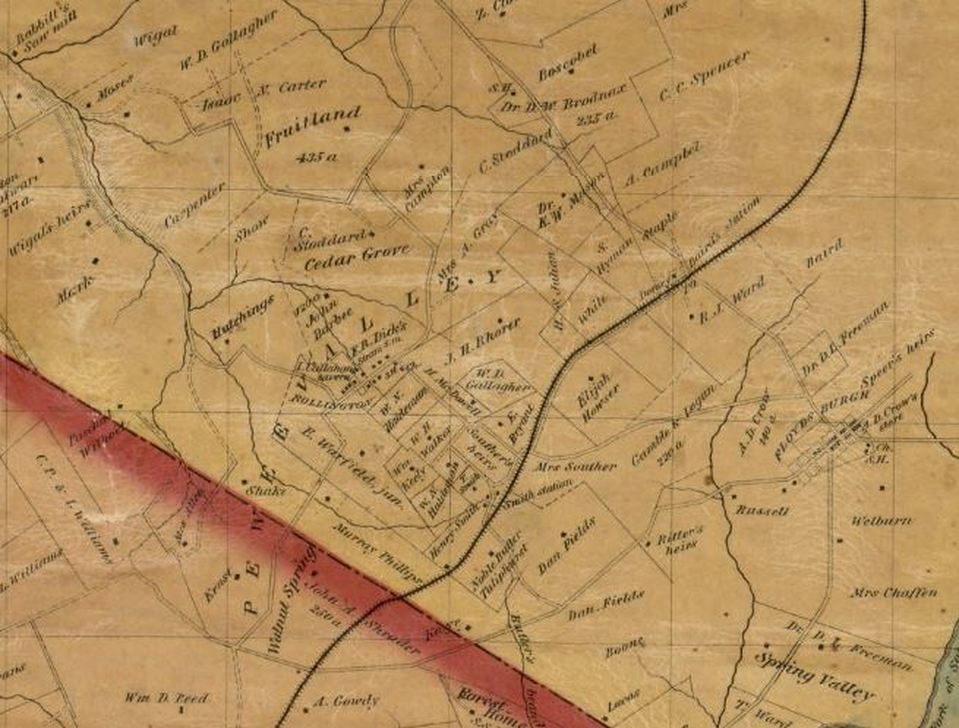

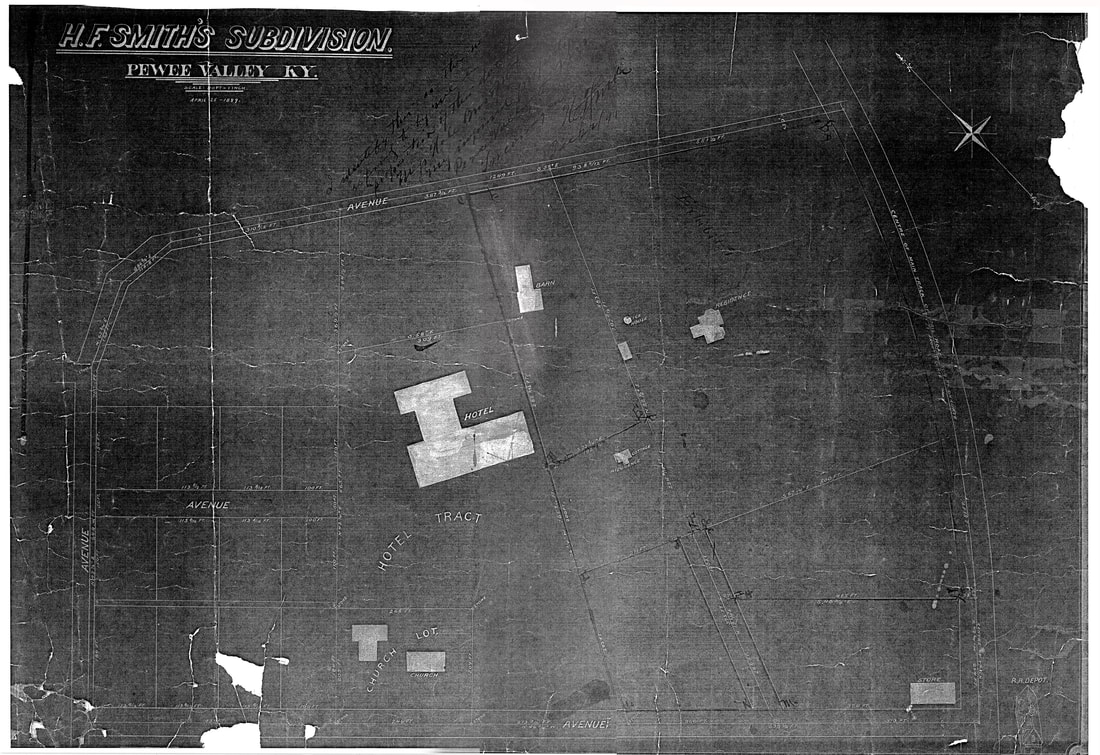

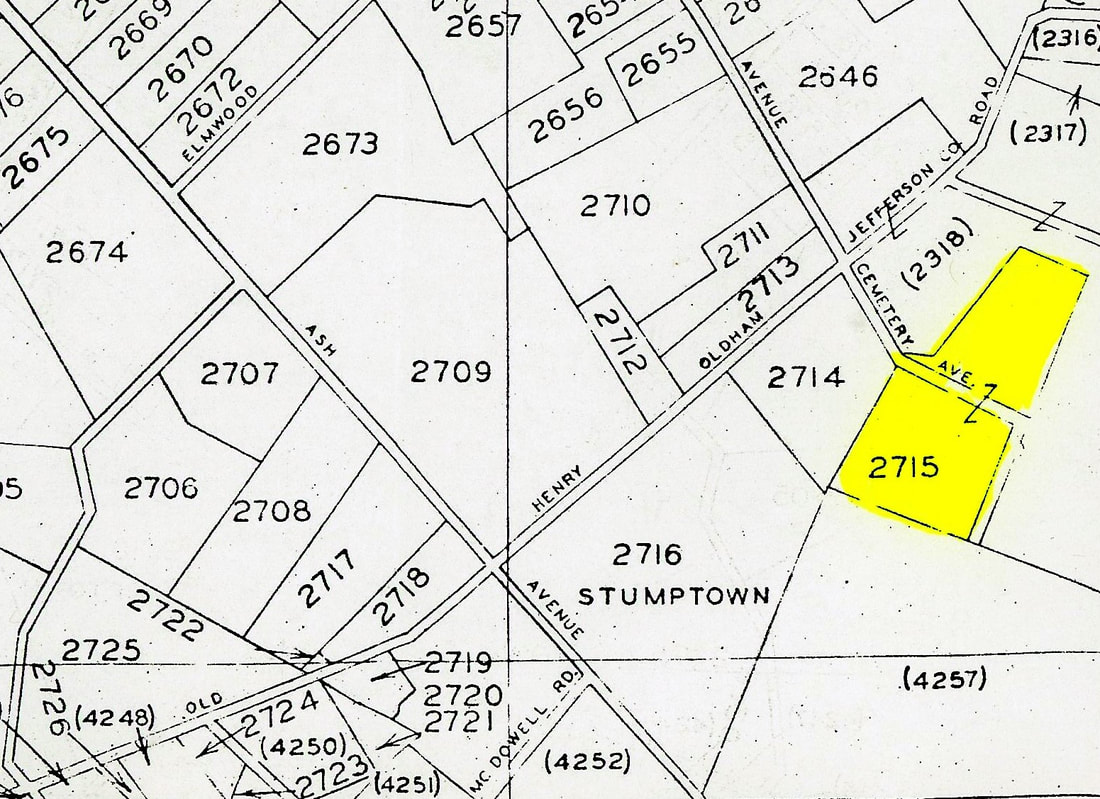

This map from Katie S. Smith's 1974 "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," pg. 18, shows that the acre of land the church and school were built on was part of the 220 acres south of the railroad tracks that Henry Smith purchased from Daniel Fields. Smith used most of the land to develop lots on Ashwood, Maple, Tulip and Elm avenues. Ironically enough, Daniel Fields owned a dozen slaves, according to tax records available through the Oldham County Historical Society.

This map from Katie S. Smith's 1974 "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," pg. 18, shows that the acre of land the church and school were built on was part of the 220 acres south of the railroad tracks that Henry Smith purchased from Daniel Fields. Smith used most of the land to develop lots on Ashwood, Maple, Tulip and Elm avenues. Ironically enough, Daniel Fields owned a dozen slaves, according to tax records available through the Oldham County Historical Society.

A title search shows that the Freedmen's Bureau originally purchased the acre of land on which the school and church were built for $108.00 from Henry and Susan Smith on April 10, 1869 .

Charles B. Cotton was named the church's trustee and was responsible for making sure the church and school were successfully completed. The reason a trustee may have been necessary was that Kentucky law required the presence of a white witness for all legal contracts. Appointing a white trustee to handle the financial arrangements between the Freedmen's Bureau and the local freedmen assured that the transaction met the letter of the law.

At the time, local attorney Charles B. Cotton

must have seemed a perfect choice for the role. On December 22, 1855, he had married Jennie M. Gallagher, the daughter of poet William D. Gallagher of Undulata/Fern Rock Cottage in Pewee Valley. Gallagher was widely-known, both before and during the war, as an abolitionist and supporter of President Abraham Lincoln. In fact, his anti-slavery sentiments so provoked his neighbors in Pewee Valley that they banded together in 1860 and demanded he leave the state. He refused their invitation, and, so the story goes, "... the stars and stripes floated above the roof of Fern Rock Cottage during the six gloomy years of the war..."

Cotton, too, had proven his fidelity to the Union cause, when he served as Surveyor of Customs for the Port of Louisville during the early years of the war. Two letters he wrote about stopping valuable supplies from reaching Confederate troops downriver are included in "The Papers of Andrews Johnson: Volume 5; 1861-1862," (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1976).

Charles B. Cotton was named the church's trustee and was responsible for making sure the church and school were successfully completed. The reason a trustee may have been necessary was that Kentucky law required the presence of a white witness for all legal contracts. Appointing a white trustee to handle the financial arrangements between the Freedmen's Bureau and the local freedmen assured that the transaction met the letter of the law.

At the time, local attorney Charles B. Cotton

must have seemed a perfect choice for the role. On December 22, 1855, he had married Jennie M. Gallagher, the daughter of poet William D. Gallagher of Undulata/Fern Rock Cottage in Pewee Valley. Gallagher was widely-known, both before and during the war, as an abolitionist and supporter of President Abraham Lincoln. In fact, his anti-slavery sentiments so provoked his neighbors in Pewee Valley that they banded together in 1860 and demanded he leave the state. He refused their invitation, and, so the story goes, "... the stars and stripes floated above the roof of Fern Rock Cottage during the six gloomy years of the war..."

Cotton, too, had proven his fidelity to the Union cause, when he served as Surveyor of Customs for the Port of Louisville during the early years of the war. Two letters he wrote about stopping valuable supplies from reaching Confederate troops downriver are included in "The Papers of Andrews Johnson: Volume 5; 1861-1862," (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1976).

H.F. Smith's Subdivision Plat, dated April 25, 1889, shows the original plan for the Villa Ridge Inn property. The residence and associated outbuildings on the plat were at one time owned by Charles Buck Cotton. From The Filson Historical Society archives, Louisville, Ky.

H.F. Smith's Subdivision Plat, dated April 25, 1889, shows the original plan for the Villa Ridge Inn property. The residence and associated outbuildings on the plat were at one time owned by Charles Buck Cotton. From The Filson Historical Society archives, Louisville, Ky.

Charles and Jennie appear to have moved to Pewee Valley shortly after the war ended. There, they owned a beautiful home on the grounds later associated with the Villa Ridge Inn and the Kentucky Confederate Home. Charles became active in the town's civic affairs and in 1866, was among the founding members of Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church. He also began speculating in Pewee Valley property through the Pewee Valley Building Association. Incorporated in 1867 by his neighbor at The Locust, Jonas Rhorer, and Henry Smith, the association's goal was to "... promote the settling up of Pewee Valley, by buying lots and building houses thereon for sale to such persons as may wish to settle in the neighborhood."

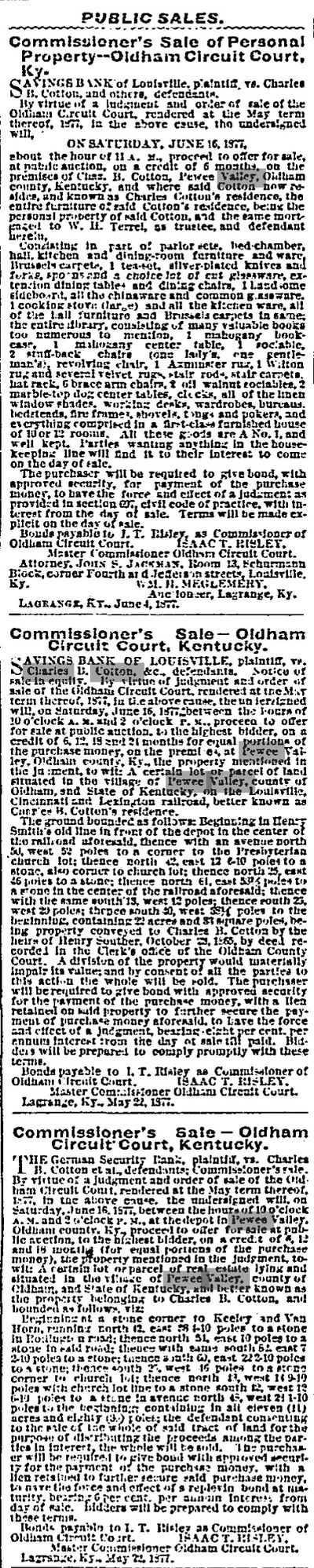

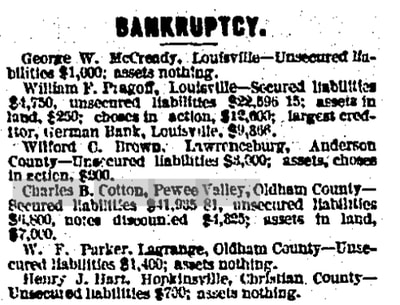

By the 1870 census, Cotton had amassed a real estate portfolio worth $40,000 -- about $680,000 in today's dollars. When the real estate market tanked during the Panic of 1873, he had mortgages due and was unable to sell his holdings. Eventually, he lost his home, his personal possessions and several additional parcels of land in Pewee Valley. On June 16, 1877, Oldham County Circuit Court, acting on behalf of the Savings Bank of Louisville, sold nearly everything he owned at auction.

Less than a year later, he declared personal bankruptcy. A May 2, 1878 Courier-Journal story about the bankruptcy listed his liabilities and assets as: $41,985.81 in secured liabilities, $6,800 in unsecured liabilities, $4,825 in discounted notes, and only $7,000 in real estate assets. He owed his creditors $4,625 more than he could pay.

On July 13, 1878, Cotton executed a quit claim deed for the grounds and improvements to the trustees of the Pewee Valley First Baptist Church. From the timing, it appears he was protecting the church and school from his creditors, who may have been considering seizing the church's property to help defray his debt. Deed Book T, page 234, at the Oldham County Courthouse reads:

This indenture of Deed of Trust made and entered into on this the 18th day of July 1878 between Chas. B. Cotton as Trustee of the first part and James Huffman, Thomas Davis, Anderson Hitt and Barlett Frazier trustees of the colored Baptist Church of Pewee Valley Oldham County Kentucky of the second part. Witnesseth That for and in consideration of the payment unto him of the monies advanced by himself towards the purchase of grounds and the erection of a suitable building for church & school purposes thereupon by the members of the colored Baptist church and furthermore in consideration of the agreement upon the part of said trustees & congregation made and entered into at the time of the donation by the Government of the United States through the Freedmen's Bureau of sufficient amount of money to complete sd. building to the effect that the same should at all times be in the use of a colored school for the benefit of the colored children of the neighborhood where desired and in consideration of the agreement upon the part of the present Trustees that said provision of sd. deed shall be complied with so as to protect him fully under a certain bond to the above effect which he the first party did Execute to the freedmen's Bureau in existence conditioned upon the advance to him of Two Hundred and Seventy five Dollars by said Bureau for the completion of said school and church building the receipt of which money is hereby acknowledged in full the party of the first part do hereby bargain & sell & convey unto the said party of the second part and their successors in office hereinafter to be chosen the following described lot of ground and improvements thereupon being in the county of Oldham State of Kentucky near Pewee Valley Depot it being the same property conveyed to the first party by Henry Smith and Susan Smith his wife Apr. 13th/69 and recorded in Deed Book O page 66 and Bounded as follows to wit Beginning w/a stake on Stone near the South side of the Old Louisville Road North 37' E 15 poles to the center of sd Road Hence S47'E 13 poles to the center of sd Road, thence S33' W 8-3/10 poles corner to Dr. A Kayes land thence North 66 W 16-4/10 poles to the beginning and containing about one and one Seventh of acres.

To have use to hold the same unto the said second party and their successors in office.

The party of the first part makes this a quit claim deed to said property & will warrant & defend the same as far as his own acts run with said property. In witness whereof he thereby attaches his own signature.

Charles B. Cotton, Trustee

That he executed the quit claim deed in both Jefferson and Oldham counties lends credence to this theory.

By the 1870 census, Cotton had amassed a real estate portfolio worth $40,000 -- about $680,000 in today's dollars. When the real estate market tanked during the Panic of 1873, he had mortgages due and was unable to sell his holdings. Eventually, he lost his home, his personal possessions and several additional parcels of land in Pewee Valley. On June 16, 1877, Oldham County Circuit Court, acting on behalf of the Savings Bank of Louisville, sold nearly everything he owned at auction.

Less than a year later, he declared personal bankruptcy. A May 2, 1878 Courier-Journal story about the bankruptcy listed his liabilities and assets as: $41,985.81 in secured liabilities, $6,800 in unsecured liabilities, $4,825 in discounted notes, and only $7,000 in real estate assets. He owed his creditors $4,625 more than he could pay.

On July 13, 1878, Cotton executed a quit claim deed for the grounds and improvements to the trustees of the Pewee Valley First Baptist Church. From the timing, it appears he was protecting the church and school from his creditors, who may have been considering seizing the church's property to help defray his debt. Deed Book T, page 234, at the Oldham County Courthouse reads:

This indenture of Deed of Trust made and entered into on this the 18th day of July 1878 between Chas. B. Cotton as Trustee of the first part and James Huffman, Thomas Davis, Anderson Hitt and Barlett Frazier trustees of the colored Baptist Church of Pewee Valley Oldham County Kentucky of the second part. Witnesseth That for and in consideration of the payment unto him of the monies advanced by himself towards the purchase of grounds and the erection of a suitable building for church & school purposes thereupon by the members of the colored Baptist church and furthermore in consideration of the agreement upon the part of said trustees & congregation made and entered into at the time of the donation by the Government of the United States through the Freedmen's Bureau of sufficient amount of money to complete sd. building to the effect that the same should at all times be in the use of a colored school for the benefit of the colored children of the neighborhood where desired and in consideration of the agreement upon the part of the present Trustees that said provision of sd. deed shall be complied with so as to protect him fully under a certain bond to the above effect which he the first party did Execute to the freedmen's Bureau in existence conditioned upon the advance to him of Two Hundred and Seventy five Dollars by said Bureau for the completion of said school and church building the receipt of which money is hereby acknowledged in full the party of the first part do hereby bargain & sell & convey unto the said party of the second part and their successors in office hereinafter to be chosen the following described lot of ground and improvements thereupon being in the county of Oldham State of Kentucky near Pewee Valley Depot it being the same property conveyed to the first party by Henry Smith and Susan Smith his wife Apr. 13th/69 and recorded in Deed Book O page 66 and Bounded as follows to wit Beginning w/a stake on Stone near the South side of the Old Louisville Road North 37' E 15 poles to the center of sd Road Hence S47'E 13 poles to the center of sd Road, thence S33' W 8-3/10 poles corner to Dr. A Kayes land thence North 66 W 16-4/10 poles to the beginning and containing about one and one Seventh of acres.

To have use to hold the same unto the said second party and their successors in office.

The party of the first part makes this a quit claim deed to said property & will warrant & defend the same as far as his own acts run with said property. In witness whereof he thereby attaches his own signature.

Charles B. Cotton, Trustee

That he executed the quit claim deed in both Jefferson and Oldham counties lends credence to this theory.

Newspaper Notices About Charles Cotton's Bankruptcy

Cotton was in similarly dire financial straits in 1890, when he executed a second deed to the First Baptist Church. Within the four-year period prior to the second deed, he had been sued twice, once for defaulting on a mortgage and once for defaulting on a guardian bond arrangement. Details of the first lawsuit appeared in the November 11, 1886 Courier-Journal:

TO FORECLOSE A MORTGAGE.

The Mutual Life Insurance Company sued Charles B. Cotton, Jennie W. (sic) Cotton, his wife, and others in the Chancery yesterday for the foreclosure of its mortgage against the defendants. They gave the plaintiffs their promissory not for $2,700, September 11, 1883, at two years. The mortgage on the lot at Sixth and Breckinridge streets was issued as security. The unpaid interest from September 11, 1885, is also asked for, besides $6,000, the estimated cost of the suit as provided by contract.

Details of the second ran in the May 7, 1889 Courier-Journal:

On a Big Judgement.

George Wolf was a petitioner in the Law and Equity Court yesterday against Charles B. Cotton. In 1868, at the latter's request, he went on the defendant's bond as the guardian of Sallie B., Willie B., and Katie B. Cotton, and bound himself that that Cotton would pay to the children any sums coming into his hands as guardian. In default of payment, J. C. Bonney was made guardian and Cotton removed, but Wolf had to pay judgments amounting to $6,230 as surety. He at once secured a judgement against Cotton and now being informed that Cotton has money in the jurisdiction of the court, seeks to attach. In addition a bill of discovery is asked. The whole debt is now $9,652.95, including interest.

TO FORECLOSE A MORTGAGE.

The Mutual Life Insurance Company sued Charles B. Cotton, Jennie W. (sic) Cotton, his wife, and others in the Chancery yesterday for the foreclosure of its mortgage against the defendants. They gave the plaintiffs their promissory not for $2,700, September 11, 1883, at two years. The mortgage on the lot at Sixth and Breckinridge streets was issued as security. The unpaid interest from September 11, 1885, is also asked for, besides $6,000, the estimated cost of the suit as provided by contract.

Details of the second ran in the May 7, 1889 Courier-Journal:

On a Big Judgement.

George Wolf was a petitioner in the Law and Equity Court yesterday against Charles B. Cotton. In 1868, at the latter's request, he went on the defendant's bond as the guardian of Sallie B., Willie B., and Katie B. Cotton, and bound himself that that Cotton would pay to the children any sums coming into his hands as guardian. In default of payment, J. C. Bonney was made guardian and Cotton removed, but Wolf had to pay judgments amounting to $6,230 as surety. He at once secured a judgement against Cotton and now being informed that Cotton has money in the jurisdiction of the court, seeks to attach. In addition a bill of discovery is asked. The whole debt is now $9,652.95, including interest.

Oldham County Deed Book Z, pg. 394, basically reiterates the quit claim deed Cotton had already executed in 1878, and again it was filed in both Jefferson and Oldham counties. Once more, he appears to have been protecting the church's property from his creditors. At the time, Kentucky law prevented blacks from testifying against whites in court. Through the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the federal government had tried to remedy the situation by providing freedmen access to federal courts. However, the Commonwealth of Kentucky challenged the federal courts' constitutionality and in 1872, the state prevailed in Blyew v. United States. Had his creditors taken the church's black trustees to court, they most likely would have lost by default.

Though a failure in business, Charles Buck Cotton was, at the very least, an honorable man and took the duties he assumed in 1869 to protect the freedmen's interests very seriously. He died on May 11, 1894, of Brights Disease at a boarding house at 414 W. Chestnut Street in Louisville, where he was living with his wife and daughter.

Though a failure in business, Charles Buck Cotton was, at the very least, an honorable man and took the duties he assumed in 1869 to protect the freedmen's interests very seriously. He died on May 11, 1894, of Brights Disease at a boarding house at 414 W. Chestnut Street in Louisville, where he was living with his wife and daughter.

About Freedmen's Bureau Schools in Kentucky

The Freedmen's Bureau's goal was to help the nation's four million slaves transition to freedom after the Civil War. Created by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, it addressed issues such as employment, food and clothing, health care, marriage legalization, abandoned property, and education throughout the South during Reconstruction.

Opening colored schools and keeping them open was an uphill battle in Kentucky. "Special and bitter" white opposition,

outright "hostility" and even violence directed at freedmen education made finding suitable school buildings a huge issue, according to the bureau's semi-annual reports. While the American Civil Liberties Union today would argue that combination church/government-supported schools are a violation of the constitution's first amendment, arrangements like the one in Pewee Valley offered a viable work-around to the much greater problem of discrimination. It became common practice, as the bureau sought to open colored schools across the commonwealth.

The Freedmen's Bureau Semi-Annual Report for Kentucky for January 1, 1867 noted that, "... The places of worship owned by the colored people are almost the only available schoolhouses in the State..."

The July 1, 1867 Kentucky report stated, "... the bureau system of renting churches of the colored people for school purposes is extending throughout the State ... There are now forty-six schools in the State, the teachers of which are paid by the bureau; that is to say, whenever the freedmen own a church or other building suitable for school purposes it is rented with the understanding that the money will go to the support of the school. The freedmen pledge themselves to pay the teacher's board, and in this way the school is successfully sustained..."

The Freedmen Population in Pewee Valley

|

|

Given Oldham County's current demographics -- the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that only 4.5 percent of residents were black or African-American in 2016 -- it may seem strange today that a colored school was needed in Pewee Valley. However, the county's racial composition was very different during the Civil War era. In 1860, about a third of Oldham's 7,283 residents were African-American. According to Darrel E. Bigham, author of "On Jordan's Banks: Emancipation and Its Aftermath in the Ohio River Valley," (University Press of Kentucky; Jan 13, 2015), Oldham was one of only six Kentucky counties where blacks accounted for more than 20 percent of the population in 1860. The others were Daviess, Henderson, Mason, Meade and Union. Many slaves were originally brought to Oldham County when settlers began arriving in the Pewee Valley vicinity at the turn of the nineteenth century. 1820 census information for what eventually became the first town to be established in this corner of the county -- Rollington -- shows that nearly two-thirds of the early settlers had slaves:

|

Some Oldham County slaveowners also engaged in what was euphemistically known as the "Black Ivory" trade -- the profitable practice of breeding slave children and selling them down the river to work on large plantations in the Deep South. This excerpt, from page 144 of "History & Families of Oldham County: The First Century 1824-1924" (Turner Publishing Co., Paducah, Ky.; 1996), describes the practice in Oldham County:

The Buckeye Cross Roads, one mile above Goshen, was so named because of a Buckeye tree that once stood at that intersection on Highway 42. The activity at this crossing was a cause of great sorrow, shame, pain and controversy, to many people of Goshen. At this crossing one could witness the loading of the "Black Maria" or slave wagon which arrived from Louisville to load human cargo for the Southern market ...

... Upon the arrival of the Black Maria, the slaves were forced into cages. Families were separated, with mothers sent to different plantations from their children and husbands placed somewhere else again. Slaves weeping and causing a disturbance were beaten with a black snake whip. Only complete submission was accepted. The Black Maria then carried its human cargo to Tarleton Landing. The slaves were then sent down the river to the southern fields. Approximately one-third of all new slaves sent into the Mississippi cotton fields and Louisiana sugar cane plantations died each year from disease and harsh conditions ...

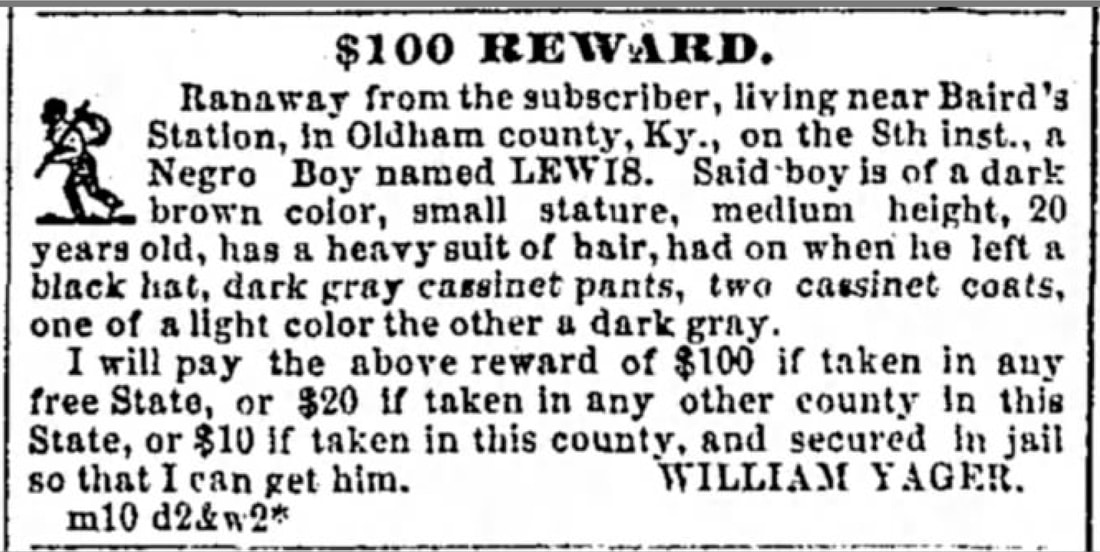

... Attempts to escape and cross the river to freedom were frequent. Sentries were sent up the river to watch for possible attempts to cross. Slaves his in cane fields near Skylight and waited for night to fall. Folklore tells of residents hearing the cane rustle at night with anxious slaves waiting for the chance to flee across the river. Retribution was swift and usually final ...

... Confirmation of cruelty that took place on the breeding plantations came by coincidence. William Belknap stopped his buggy to give a gentleman a lift. During their time in travel, the passenger revealed he had been an overseer on one of these farms. His name was Guyton. He told Belknap of the whippings which were delivered and followed by salting of the wounds to make them sting...

The Buckeye Cross Roads, one mile above Goshen, was so named because of a Buckeye tree that once stood at that intersection on Highway 42. The activity at this crossing was a cause of great sorrow, shame, pain and controversy, to many people of Goshen. At this crossing one could witness the loading of the "Black Maria" or slave wagon which arrived from Louisville to load human cargo for the Southern market ...

... Upon the arrival of the Black Maria, the slaves were forced into cages. Families were separated, with mothers sent to different plantations from their children and husbands placed somewhere else again. Slaves weeping and causing a disturbance were beaten with a black snake whip. Only complete submission was accepted. The Black Maria then carried its human cargo to Tarleton Landing. The slaves were then sent down the river to the southern fields. Approximately one-third of all new slaves sent into the Mississippi cotton fields and Louisiana sugar cane plantations died each year from disease and harsh conditions ...

... Attempts to escape and cross the river to freedom were frequent. Sentries were sent up the river to watch for possible attempts to cross. Slaves his in cane fields near Skylight and waited for night to fall. Folklore tells of residents hearing the cane rustle at night with anxious slaves waiting for the chance to flee across the river. Retribution was swift and usually final ...

... Confirmation of cruelty that took place on the breeding plantations came by coincidence. William Belknap stopped his buggy to give a gentleman a lift. During their time in travel, the passenger revealed he had been an overseer on one of these farms. His name was Guyton. He told Belknap of the whippings which were delivered and followed by salting of the wounds to make them sting...

Legend has it that the spirit of one of the overseers who was quite free with his whip cannot rest to this day and "... comes back at night and wanders across the country, surrounded by a chorus of wailing slave mothers and their children that his whip had driven apart..." (Courier-Journal, October 5, 1940, "Oldham Hant Roves County with a Past")

Though many Oldham County residents were against slavery, slave ownership in Pewee Valley's vicinity remained common during the years immediately preceding the Civil War. A look at the tax schedules for known property owners in the area during the late 1850s, available at the Oldham County History Center's archives, shows the following owned slaves:

|

|

After the Civil War, some freedmen stayed. And the school and church, the newly-established freedmen communities of Stumptown and Frazier Town, and the availability of railroad transportation may have attracted others. African-American surnames in the 1870 Pewee Valley Census included:

|

|

|

Most were farming, working as farm laborers or employed as domestic servants. There were also several blacks who worked for the railroad and were boarding at the Section House located at the corner of what is now Mt. Mercy Avenue and Houston Lane.

Cessation of Freedmen's Bureau Operations in Kentucky

Unfortunately, the Freedmen's Bureau's tenure in Kentucky was short-lived. According to an article written by Rob Knox for the Kentucky Historical Society in 2013, "The Tribulations of the Freedman's Bureau in Kentucky":

In July of 1868, the local agencies of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Unclaimed Lands ceased operations... In an open letter to “the freed people of Kentucky,” the assistant commissioner of the bureau in Kentucky, Benjamin Runkle, celebrated the success of the Bureau and the readiness of Kentucky’s white and black population to coexist in relative harmony without continued federal involvement in the state’s affairs. The letter states, “[t]he results of the efforts of the Bureau, since its establishment, have been eminently satisfactory…The government has liberated, protected, fed, clothed and educated you. It is the act of a just and generous people, and the officers of the Bureau are not ashamed of their share in the work.”

After establishing the Bureau’s Kentucky legacy as one of success, the letter continues on to address Kentucky’s preparedness for a fair and just biracial society. Runkle wrote:

“[t]he Assistant Commissioner hopes that the white people of Kentucky, recognizing the fact that intelligent labor is necessary for their prosperity, will lend you a helping hand…The Assistant Commissioner trusts…that you [blacks] will cultivate friendly relations with the white people of Kentucky…and, in fine that you may continue the work of fitting yourselves to secure and enjoy the rights and privileges of American citizens.”

Seemingly, at the conclusion of the Bureau’s short tenure in Kentucky most of the problems other states were facing in the midst of Reconstruction had been eradicated, but this letter was meant as an encouragement to the people who were largely being left to fend for themselves without federal support. A closer inspection of the Bureau’s history and success rate in Kentucky reveals a much more difficult situation made worse by Bureau shortages of funds and manpower and amplified by white Kentuckians racism and disdain towards the Bureau and its activities.

Kentucky’s unique position as a Union state that was fighting to retain slavery in the Civil War’s early years draws light on its anti-federal stance during Reconstruction. Many Kentuckians felt like the federal government was treating them as conquered territory instead of a loyal state, and at the heart of this battle between white Kentuckians and the federal government was the status of blacks and the abolition of slavery. As blacks earned more rights throughout the Reconstruction years, Kentuckians turned further and further away from their Union identity and started to more closely align themselves with the defeated ex-Confederate states. Tellingly, it was not until 1891 that Kentucky’s Constitution was amended to recognize the abolition of slavery, and the Civil War Amendments were not ratified until 1976 during the bicentennial festivities. Amidst the hostility the installation of local Freedmen’s Bureaus was obviously not well received and never accepted by the majority of whites across the state...

Pewee Valley wasn't much different than the rest of the state in their attitude towards African-Americans. Many white residents had sided with the Confederacy during the war. Blacks didn't gain the right to vote in local elections until 1890, when the town received a new charter from the Kentucky Legislature.

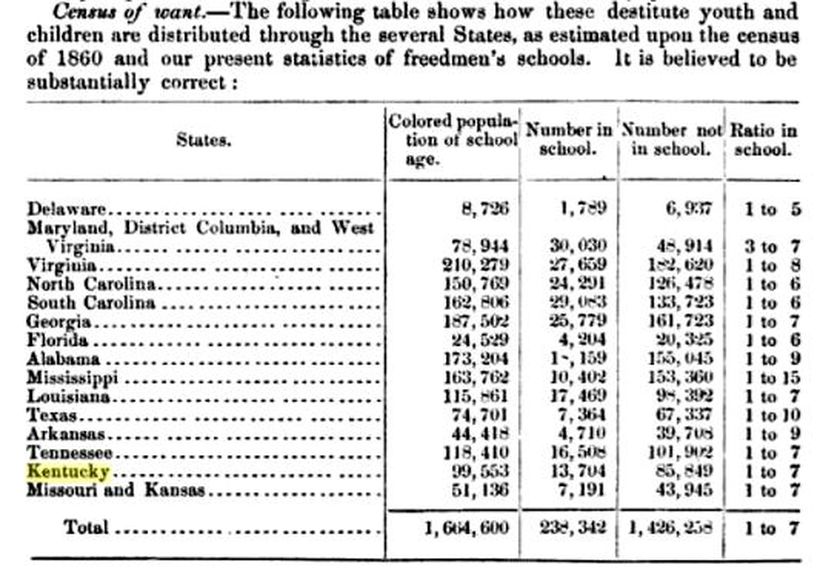

However, Pewee Valley's freedmen were better off than many in Kentucky, because they had a school that could provide their children with at least a rudimentary education. The bureau's semi-annual report issued January 1, 1868 included this

table showing that only one in seven of Kentucky's black children of school age were enrolled in school at that time:

table showing that only one in seven of Kentucky's black children of school age were enrolled in school at that time:

Schooling for Kentucky's African-Americans remained a significant problem for many years. Page 193 of "The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia" by Gerald L. Smith, Karen Cotton McDaniel, John A. Hardin (University Press of Kentucky, Jul 16, 2015) explains that adequate funding for colored schools was a major issue until 1882:

... On March 9, 1867, the Kentucky Legislature allocated a small per student payment to black schools from black tax revenues. Because of the impoverished condition of most Kentucky blacks, these measures realized very little for the schools ...

... On February 23, 1874, after the Freedmen's Bureau was dissolved, Kentucky created a uniform school system for blacks and allocated to it all administrative duties except funding, which still came from taxes on blacks and was controlled by the state.

On April 24, 1882, the Kentucky legislature allocated money for black schools to come from the same fund as that for white institutions on a pro rata basis. This measure ensured the continuation of education for blacks in Kentucky.

... On March 9, 1867, the Kentucky Legislature allocated a small per student payment to black schools from black tax revenues. Because of the impoverished condition of most Kentucky blacks, these measures realized very little for the schools ...

... On February 23, 1874, after the Freedmen's Bureau was dissolved, Kentucky created a uniform school system for blacks and allocated to it all administrative duties except funding, which still came from taxes on blacks and was controlled by the state.

On April 24, 1882, the Kentucky legislature allocated money for black schools to come from the same fund as that for white institutions on a pro rata basis. This measure ensured the continuation of education for blacks in Kentucky.

Passage of the Day Law -- "An Act to Prohibit White and Colored Persons from Attending the Same School" -- in March 1904 would ensure that Kentucky schools remained segregated for another half-century. The law prohibited black children from attending the same schools as whites. Not until the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in the landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, did Kentucky's Day Law became illegal.

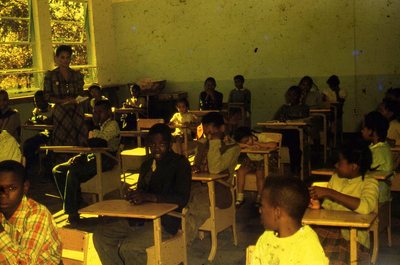

This photo, showing students at the Pewee Valley Colored School, appears to have been taken prior to 1950, when the

Oldham County Board of Education replaced the original Freedmen's Bureau facility on the First Baptist Church of Pewee Valley's property with a new facility on Ash Avenue. Photo from

"Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel" published by Katie S. Smith in 1974.

School Records

Records from the school's earliest years of operation have not been found. It was not until the 1890s, after the Oldham County Board of Education was required by state law to survey the schools, that any written records are available. In 1896, the Kentucky Department of Education published a "Report of the Superintendent Public Instruction of the State of Kentucky for Two Years Ended June 30, 1895,"(Capital Printing Co, Frankfort, Ky.; 1896). J.L. Reeves, Superintendent for the Oldham County Board of Education, provided the statistics on the condition of both white and colored schools in the county.

His report showed there were 24 white school districts, serving 1,444 students; and eight colored school districts, serving 667 students, in Oldham County. Only nine white schools and one colored school offered students more than five months of education per year. According to the Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, operated by the University of Kentucky, the Pewee Valley Colored School didn't receive funding to extend the school term to nine months until 1932.

There were three male and six female African-American teachers employed by the school system. Presumbly, all were teaching at the eight colored schools. Freedmen's Bureau reports from the limited time they were actively working in Kentucky made of point of noting that Kentucky freedmen preferred black teachers. That preference didn't appear to change over the next thirty years.

None of the African-American teachers were "normal school" graduates -- i.e. graduates of college programs specifically designed to train teachers, such as the program offered at Berea College; however, it should be noted that none of the 26 white teachers employed by Oldham County were normal school graduates, either! Most teachers -- black and white -- earned teaching certificates through the county.

|

|

The Pewee Valley Historical Society has been unable to identify most of the teachers at the Pewee Valley Colored School. Four are known from census data and the Notable Kentucky African Americans Database.

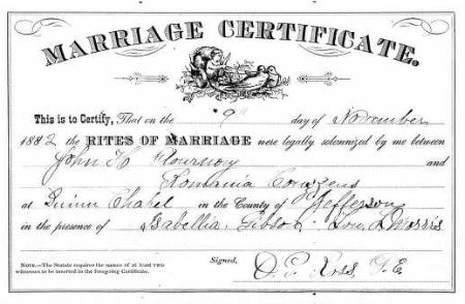

The first two were sisters, Hattie L., age 25, and Bessie A. Davis, age 23. They were the daughters of Thomas and Teedee Davis and lived in Frazier Town with their parents, sisters, little brother, and niece. The 1910 census listed their occupations as "schoolteacher." Both women had attended the Pewee Valley Colored School as children. The 1900 census of the Frazier Town area lists both of them as being "At School." The third, Romania Booker "Mollie" Cozzens Flournoy (September 28, 1869-April 2, 1940), was a teacher at the school from at least 1916 through 1924, according to the Notable African Americans Database. She was 47 at the time she began teaching and had been widowed by 1910. On November 9, 1882, at Quinn Chapel in Louisville, she had married John Herman Flournoy. He was a gardener by trade and, unlike his new wife, could neither read nor write. They had 12 children, of which eight have been identified:

In 1910, Romania was living on Fraziertown Road, working for herself as a laundress, and had six of her unmarried children still under her roof. Only one of them, Eugene, was employed. He was working as a waiter at the Kentucky Confederate Home. By the 1920 census, she was still living on Fraziertown Road, but her occupation was listed as schoolteacher. Living with her was her married daughter, Martha; her son-in-law Abel N. Hewitt, who was a preacher of the gospel; and their four children; as well as Martin, Raymond, Clifford and Laura. Both Martin and Raymond were working at the Confederate Home, Martin as a nurse and Raymond as a waiter. By the 1930 census, she was living on Huston Lane with her youngest son, James Clifford, and had retired. She died at 11:45 p.m. on April 2, 1940 at the home of her son Raymond, 1703 Hale Avenue in Louisville, and was buried at Pewee Valley Cemetery East. |

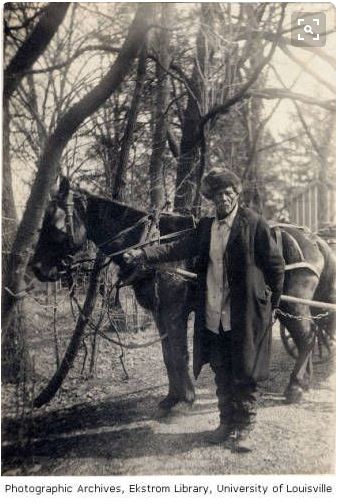

The fourth schoolteacher found from census data was Sallie Winrow. She was the daughter of Edmund and Lucy Parker. The Parker family had been living in Frazier Town since soon after the African-American settlement was founded. Her parents' home appears on the 1879 Beers & Lanagan Atlas. Sallie was 16 years old in 1880 and was already employed as a domestic servant. She was still living with her family in 1900, but was not living with them in Frazier Town in 1910. At that point, she had likely married, and was living with her husband.

The marriage did not last long. By 1920, she was widowed and had moved back to her childhood home in Frazier Town. The census listed her occupation as school teacher. Her widowed brother, Abe Parker, was the head of the household. Also living there was their mother, Lucy; sister Bessie, who was employed as a family cook; and widowed sister, Arena or "Rena" Jefferson, who worked as a hair dresser.

The marriage did not last long. By 1920, she was widowed and had moved back to her childhood home in Frazier Town. The census listed her occupation as school teacher. Her widowed brother, Abe Parker, was the head of the household. Also living there was their mother, Lucy; sister Bessie, who was employed as a family cook; and widowed sister, Arena or "Rena" Jefferson, who worked as a hair dresser.

Kate Matthews photo of Abe Parker, his wagon and his horse. He was the brother of Sallie Winrow, an African-American schoolteacher at Pewee Valley School in the 1920s. From the Kate Matthews Collection, University of Louisville Photographic Archives, Item no. ULPA 1984.24.198.p

Kate Matthews photo of Abe Parker, his wagon and his horse. He was the brother of Sallie Winrow, an African-American schoolteacher at Pewee Valley School in the 1920s. From the Kate Matthews Collection, University of Louisville Photographic Archives, Item no. ULPA 1984.24.198.p

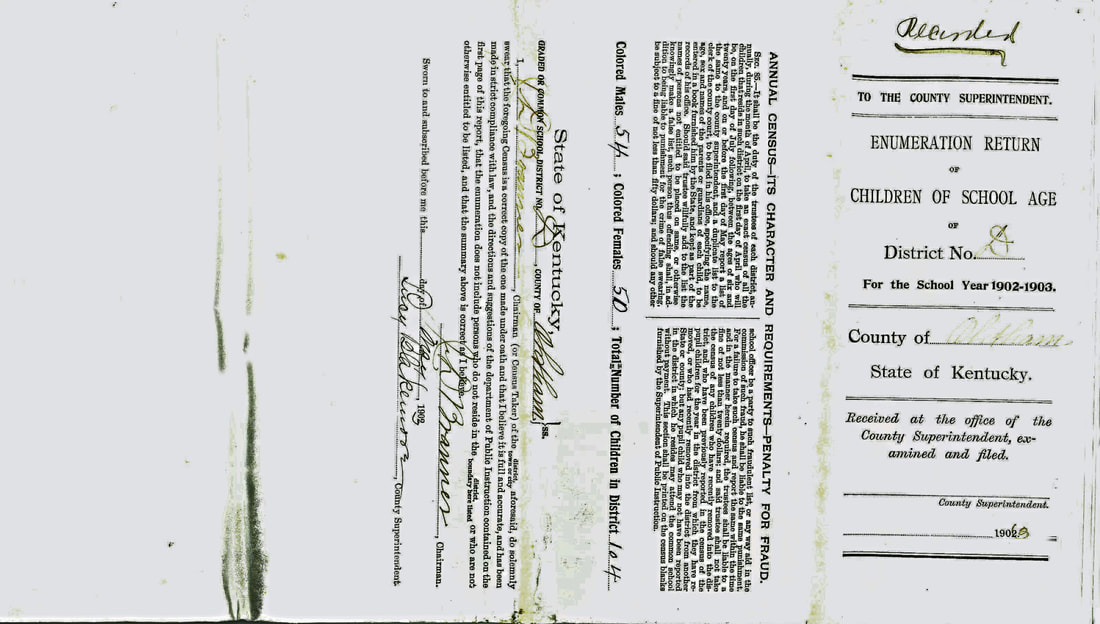

Pupil records available at the Oldham County History Center in LaGrange, Ky., for the Pewee Valley Colored School, referred to as District D in the reports, include:

These records have been scanned by the Pewee Valley Historical Society and are available online here.

The children of John Herman and Romania B. Cozzens Flournoy are listed as students at the Pewee Valley Colored School in some of these reports.

- 1900-1901 Kentucky State Census Report for Oldham County Schools, District D, Colored School

- 1901-1902 Kentucky State Census Report for Oldham County Schools, District D, Colored School

- 1902-1903 Kentucky State Census Report for Oldham County Schools, District D, Colored School

- 1911-1912

- 1922

- 1926

- 1928

- 1930

- 1934

These records have been scanned by the Pewee Valley Historical Society and are available online here.

The children of John Herman and Romania B. Cozzens Flournoy are listed as students at the Pewee Valley Colored School in some of these reports.

Author Annie Fellows Johnston Described the Hardships Local Freedmen Faced Getting an Education

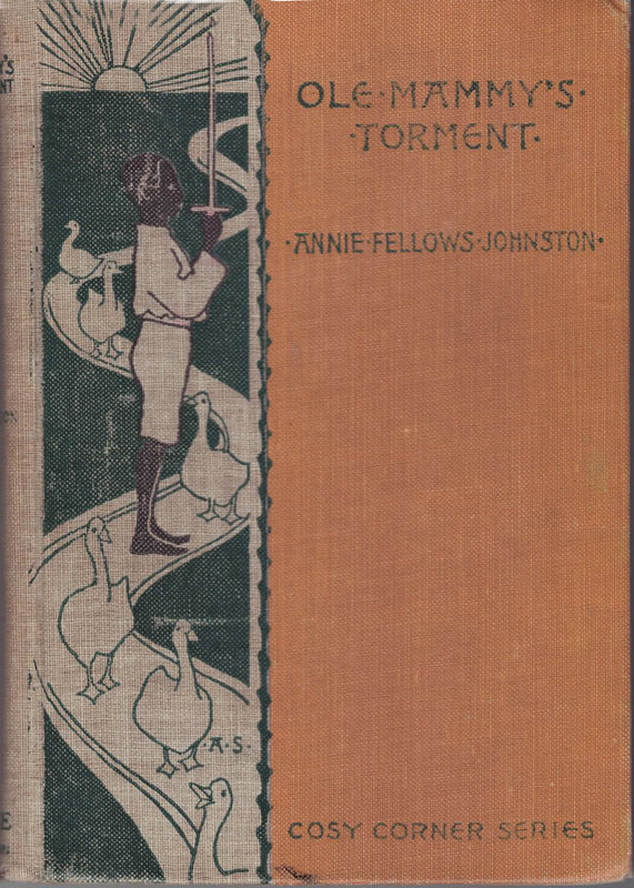

Turn-of-the-20th-century author Annie Fellows Johnston was an astute observer and chronicler of the people, customs and cultures with which she came in contact during her life. Her inspirational children's novels were loosely based on real people and places in Kentucky, France, Indiana, Arizona, California and Texas. In 1895, she published her first book based on her experiences while visiting Pewee Valley. That book, "The Little Colonel," launched her career as a children's publishing phenomenon on par with Louisa May Alcott and marked the start of a series that wasn't completed until 1912 with the publication of "Mary Ware's Promised Land."

Two years later, in 1897, she published "Ole Mammy's Torment." While "The Little Colonel" was based on her experiences with Pewee Valley's wealthy white families, "Ole Mammy's Torment" offered a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the lives of the freedmen who labored in white fields and homes as servants.

The three main African-American characters in the story are grandmother Sheba, who often worked as a cook for a white family at Rosehaven and was raising her three grandchildren; John Jay, her mischievous grandson; and the Rev. George Chadwick, who had gone North to obtain an education, and had recently returned to Pewee Valley to die, his lofty ambition to help his people cruelly cut short by tuberculosis. Inspired by Rev. Chadwick's example, John Jay casts aside his idle ways and eventually decides to learn to read the books he inherits at the preacher's death. The excerpts below are from the book's conclusion, Chapter IX, when John Jay shocks his grandmother Sheba by asking to attend the local colored school:

... her surprise knew no bounds when he came slowly into the cabin one evening, and asked if he might be allowed to start to school the following week.

"Law, chile!" she answered. "They isn't any school for cul'ud folks less'n a mile an' a half away, an' besides, you hasn't clothes fitten to wear. The scholars would all laugh at you."

Still he persisted. "What put such a notion in yo' head, anyhow?" she demanded.

John Jay turned his face aside, and busied himself with taking another reef in his suspenders. "The Rev'und Gawge wanted me to go," he said, in a low tone. "Besides, how can I know what all's in the books he done left me 'thout I learn to read?"

"That's so," assented Mammy, looking proudly at the shelves now ornamenting one corner of the little cabin with George's well-worn school-books. Most of the volumes were upside down, because her untutored eyes knew no better than to replace them so, when she took them out to dust them with loving care. They were George's greatest treasures, and she allowed no one to touch them, not even John Jay, to whom they had been left.

"What does a little niggah like him want of schoolin'," she had once said to Uncle Billy, when he had proposed sending the boy to school to keep him out of mischief. "Why, that John Jay he hasn't got any mo' mind than a grasshoppah. All he knows how to do is jus' to keep on a jumpin'. No, brer Billy, it would be a pure waste of good education to spend it on anybody like him."

John Jay had always cheerfully agreed with this opinion, which she never hesitated to express in his hearing. He had had no desire to give up his unlettered liberty until that day on the haymow when he had his awakening. Having heard Mammy's opinion so often, it was no wonder that he kept his head turned bashfully aside, and stumbled over his words when he timidly made his request. It was the sight of George's books that gave him courage to persist, and it was the sight of the books that decided Mammy's answer. She could remember the time when Jintsey's boy had been almost as light-headed and light-hearted as John Jay; so it was not past belief that even John Jay might settle down in time.

The thought that he might some day be able to read the books that George had pored over, and that, possibly, some time in the far future he might be fitted to preach the gospel George had proclaimed, aroused all her grandmotherly pride. Some fragment of a half-forgotten sermon floated through her mind as she looked on the ragged little fellow standing before her.

"The mantle of the prophet 'Lijah done fell on his servant 'Lisha," she muttered under her breath. "What if the mantle of Gawge Chadwick have been left to my poah Ellen's boy, 'long with them books?"

John Jay was balancing himself on one foot, while he drew the toes of the other along a crack in the floor between the puncheons, anxiously awaiting her decision. Not knowing what was passing through her mind, he was not prepared for the abrupt change in both her speech and manner. He almost lost his balance when she suddenly gave her consent; but, regaining it quickly, he tumbled through the door, giving vent to his delight in a series of whoops that made Mammy's head ring, and brought her to the door, scolding crossly. A few minutes later, a dusky little figure crept through the gloaming, and rustled softly through the leaves lying on the path. Resting his arms on the fence, he looked across the dim fields to the darkly outlined tree-tops of the hill beyond.

"I wondah if he knows that I'm keepin' my promise," he whispered. "I wondah if he knows I'm tryin' to follow him." Over the churchyard hill the new moon swung its slender crescent of light, and into its silvery wake there trembled out of the darkness a shining star.

* * * * *

The roadside ditches are covered with ice, these cold winter mornings. The ruts in the muddy pike are frozen as hard as stone. John Jay shuffles along in his big shoes on his way to school, out at the toes and out at his elbows; but there is a broad smile all over his bright little face. Wherever he can find a strip of ice to slide across, he goes with a rush and a whoop. Sometimes there is only a raw turnip and a piece of corn pone in his pocket for dinner. His feet and fingers are always numb with cold by the time he reaches the school house, but his eyes still shine, and his whistle never loses its note of cheeriness. There are whippings and scoldings in the schoolhouse, just as there have always been whippings and scoldings in the cabin; for no sooner is he thawed out after his long walk, than he begins to be the worry of his teacher's life, as he was the torment of Mammy's. It is not that he means to make trouble. Despite his many blunders into mischief, he is always at the head of his class, for he has a motive for hard study that the other pupils know nothing of.

Every evening Bud and Ivy watch for his home-coming with eager faces flattened against the cabin window, lit up by the red glare of the sunset. They see him come running up the road, snapping his cold fingers, and turning occasional handsprings into the snow-drifts in the fence corners.

Just before he comes whistling up the path with his face twisted into all sorts of ugly grimaces to make them laugh, he stops at the gate a moment. Do they wonder what he always sees across those snowy fields, as he stands and looks away towards Mars' Nat's cottage and the white churchyard on the hill?

Ah, Bud and Ivy have not had their awakening; but the little brother and sister are not the only ones who fail to see more than the surface of John Jay's nature. Under the bubbles of his gay animal spirits runs the deep current of a strong purpose, and in these moments he is keeping silent tryst with a memory. He thinks of his promise, and his heart goes out to his Reverend George on the other side of the toll-gate.

This home, once known as Delacoosha, stood on the property that is now Mt. Mercy Place subdivision. At the time "Ole Mammy's Torment" was written, it was owned by the Burge family and likely served as the model for Rosehaven in the story. Photo from the Fox Film Scrapbook at the Oldham County History Center.

Annie Fellows Johnston's stepdaughter Mary Gardner Johnston helped illustrate "Ole Mammy's Torment," and according to a February 9, 1901 Courier-Journal interview, used real people and places in Pewee Valley and neighboring Floydsburg as her models.

Rosehaven was probably based on the Burge home, which stood on what is now the site of Mt. Mercy Place subdivision and did, indeed, have a porch with "white rose-twined pillars." The abandoned Brier Hill chapel, where Rev. George Chadwick played the organ, appears to be based on St. James Episcopal Church, which had been through many hard times since its founding and had even been padlocked for a time. Also real was the toll gate. In 1886, a group of Peweeans had built a turnpike road from the end of Ash Avenue to the iron bridge at Floyd's Fork. The tollgate would have been within walking distance of the freedmen settlement at Stumptown, near the Pewee Valley First Baptist Church and school. The whereabouts of Sheba's cabin is unknown. The white family that owned Rosehaven may have been based on the Burges, who owned "Rosehaven" -- or "Delacoosha" in real life. And just like in the story, their daughter's name was Hallie.

Rosehaven was probably based on the Burge home, which stood on what is now the site of Mt. Mercy Place subdivision and did, indeed, have a porch with "white rose-twined pillars." The abandoned Brier Hill chapel, where Rev. George Chadwick played the organ, appears to be based on St. James Episcopal Church, which had been through many hard times since its founding and had even been padlocked for a time. Also real was the toll gate. In 1886, a group of Peweeans had built a turnpike road from the end of Ash Avenue to the iron bridge at Floyd's Fork. The tollgate would have been within walking distance of the freedmen settlement at Stumptown, near the Pewee Valley First Baptist Church and school. The whereabouts of Sheba's cabin is unknown. The white family that owned Rosehaven may have been based on the Burges, who owned "Rosehaven" -- or "Delacoosha" in real life. And just like in the story, their daughter's name was Hallie.

Illustrations from "Ole Mammy's Torment

The School's Final Chapter

The original Pewee Valley Colored School remained in operation until after WWII. While Pewee Valley's white school closed its doors gradually over the years after Crestwood School opened in 1916, African-American students continued to attend the two-room schoolhouse built in 1869. It then became known simply as Pewee Valley School.

James Harris (born July 17, 1931) attended the original school. In a phone interview conducted April 23, 2018, he described what it was like:

There were just two rooms. One side of the school was for beginners, then the older kids went into the second room... It had a concrete slab porch across the front and you could go into two doors, one for each classroom ... The beginner room had a stage across the front and about every three months, the teachers would put on programs. The kids made homemade candy to sell and wrapped it in wax paper ... They used the stage for the end of the year graduating program, too ... In the beginner room we had big desks where two people sat at one desk ... We got recess every day. You would bring your lunch. Maybe once a month, the older kids would cook and serve the younger kids a special lunch, mostly hot dogs ... We had a sliding board and swings with wooden seats. There were a couple of sandpits for things like maybe horseshoes... They had an outdoor bathroom (editor's note: a privy) built out of concrete blocks. The janitor kept it clean and nice. The girls were on one side and the boys on the other. In the middle of the building was where you kept the coal for the stove ... The boys took turns gathering kindling and putting it in the stove. Whoever got to school first made a fire ... Most of the kids lived in the neighborhood and walked to school or rode bikes. The kids in Frazier Town took a bus ... Most kids went to Lincoln Institute to have fun. They had black kids there from all over. We went to basketball games and to field day once a year. It was a heck of a good time ...

There were just two rooms. One side of the school was for beginners, then the older kids went into the second room... It had a concrete slab porch across the front and you could go into two doors, one for each classroom ... The beginner room had a stage across the front and about every three months, the teachers would put on programs. The kids made homemade candy to sell and wrapped it in wax paper ... They used the stage for the end of the year graduating program, too ... In the beginner room we had big desks where two people sat at one desk ... We got recess every day. You would bring your lunch. Maybe once a month, the older kids would cook and serve the younger kids a special lunch, mostly hot dogs ... We had a sliding board and swings with wooden seats. There were a couple of sandpits for things like maybe horseshoes... They had an outdoor bathroom (editor's note: a privy) built out of concrete blocks. The janitor kept it clean and nice. The girls were on one side and the boys on the other. In the middle of the building was where you kept the coal for the stove ... The boys took turns gathering kindling and putting it in the stove. Whoever got to school first made a fire ... Most of the kids lived in the neighborhood and walked to school or rode bikes. The kids in Frazier Town took a bus ... Most kids went to Lincoln Institute to have fun. They had black kids there from all over. We went to basketball games and to field day once a year. It was a heck of a good time ...

Berea Hall was the main building on the Lincoln Institute's campus

Berea Hall was the main building on the Lincoln Institute's campus

Lincoln Institute was an all-black high school located near Simpsonville in Shelby County. According to Wikipedia:

... the school was created by the trustees of Berea College after the Day Law passed the Kentucky Legislature in 1904. It put an end to the racially integrated education at Berea that had lasted since the end of the Civil War ... The founders originally intended Lincoln to be a college as well as a high school, but by the 1930s it gave up its junior college function. Lincoln offered both vocational education and standard high school classes. The students produced the school's food on the campus' 444 acres ...

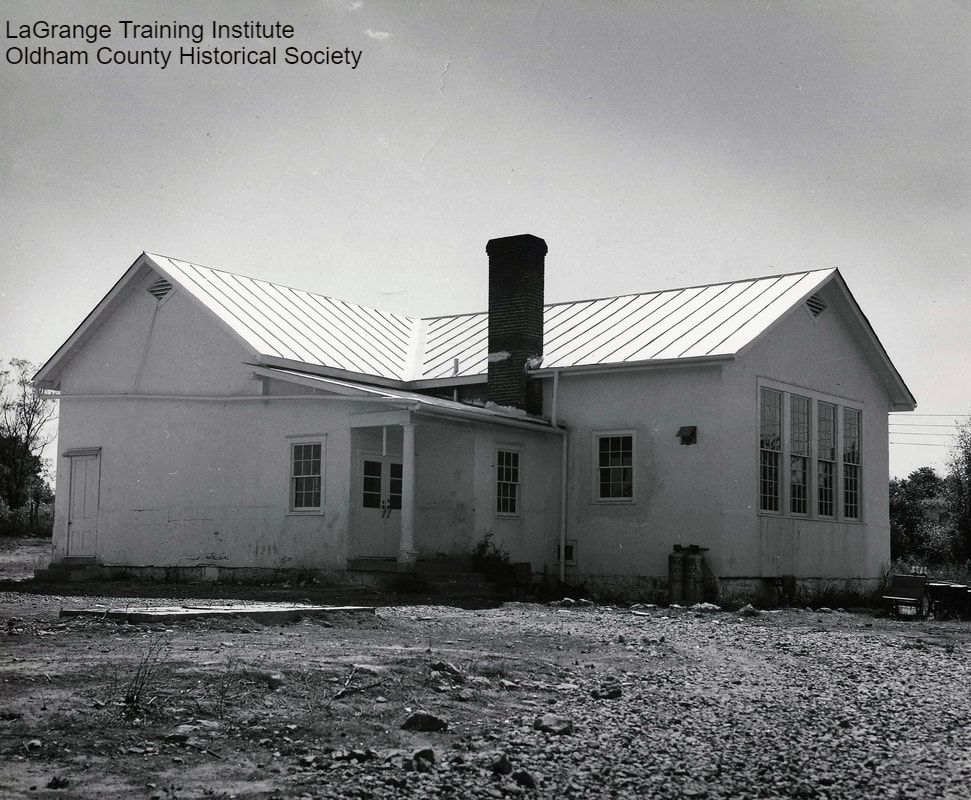

Although Oldham County operated an African-American school in LaGrange for children in grades 1-10, those who wanted to continue their educations were sent to Lincoln Institute. As the county's black population declined, the LaGrange Training School eventually discontinued high school classes. The Oldham County Board of Education's meeting minutes for March 2, 1948, noted:

On a motion by Mr. Mount seconded by Mr. Clore and duly carried the board voted to discontinue the 9th and 10th grades at the LaGrange Training School at the close of the present school year and to transport the colored High School pupils to Lincoln Institute.

At the same meeting, the board discussed options for educating the county's black children in the Prospect/ Goshen/ Skylight area:

The superintendent discussed the possibility of contracting with the Jefferson County Board of Education for the education of colored children on Highway #42. On motion of Mr. Clore seconded by Mr. Mount and duly carried the superintendent was authorized to work out such a contract with the Jefferson County Board, decision on said contract to be made when it is presented to the Oldham County Board of Education at a later meeting.

... the school was created by the trustees of Berea College after the Day Law passed the Kentucky Legislature in 1904. It put an end to the racially integrated education at Berea that had lasted since the end of the Civil War ... The founders originally intended Lincoln to be a college as well as a high school, but by the 1930s it gave up its junior college function. Lincoln offered both vocational education and standard high school classes. The students produced the school's food on the campus' 444 acres ...

Although Oldham County operated an African-American school in LaGrange for children in grades 1-10, those who wanted to continue their educations were sent to Lincoln Institute. As the county's black population declined, the LaGrange Training School eventually discontinued high school classes. The Oldham County Board of Education's meeting minutes for March 2, 1948, noted:

On a motion by Mr. Mount seconded by Mr. Clore and duly carried the board voted to discontinue the 9th and 10th grades at the LaGrange Training School at the close of the present school year and to transport the colored High School pupils to Lincoln Institute.

At the same meeting, the board discussed options for educating the county's black children in the Prospect/ Goshen/ Skylight area:

The superintendent discussed the possibility of contracting with the Jefferson County Board of Education for the education of colored children on Highway #42. On motion of Mr. Clore seconded by Mr. Mount and duly carried the superintendent was authorized to work out such a contract with the Jefferson County Board, decision on said contract to be made when it is presented to the Oldham County Board of Education at a later meeting.

The LaGrange Training Institute/School functioned as an elementary school and high school through grade 10 until the fall of 1948. Pewee Valley's African-American students attended the high school, and those who opted to continue their educations graduated from the Lincoln Institute in Shelby County. Photo courtesy of the Oldham County Historical Society.

In the days before expressways, the bus ride to Lincoln Institute was long. Students from the LaGrange area were picked up first. Then the bus picked up Pewee Valley's students, who waited WHERE? The bus route took them down Ash Avenue to _____, then to _____, and finally to U.S. 60, the old Louisville-Shelbyville Road.

In 1947, the Oldham County Board of Education began planning to improve school facilities across the county. Between 1930 and 1950, population had increased by almost 50 percent, from 7,402 to 11,018. Schoolrooms were overcrowded. Facilities were outdated. An initial proposal, prepared for the board by Wendell Trapp and Elliott Lee, detailed the issues the school system was facing:

Oldham County Schools are at their crisis. Year by year for twenty years the school building facilities of the county have been reduced. Year by year the remaining facilities have depreciated. This coming school year nearly 2,000 children will be crowded into buildings designed originally for little more than half that number. Furthermore these buildings are so worn, so poorly lighted, heated and ventilated; so unsanitary and unsafe that even a pauper county might well be ashamed of them. And Oldham County is not a pauper county ...

... In the two largest schools the high school and grade school pupils are intermingled and in almost constant contact. This deprives the older children of the right to their separate adolescent life undisturbed by the heckling of the smaller ones and because of the tendency of young children to be too much interested in and to ape the activities of the older ones, it deprives the grade school children on their right and need to be simply children ...

... The situation is now intolerable. There is no choice between doing and not doing. The problem must be resolved and solved -- now.

Oldham County Schools are at their crisis. Year by year for twenty years the school building facilities of the county have been reduced. Year by year the remaining facilities have depreciated. This coming school year nearly 2,000 children will be crowded into buildings designed originally for little more than half that number. Furthermore these buildings are so worn, so poorly lighted, heated and ventilated; so unsanitary and unsafe that even a pauper county might well be ashamed of them. And Oldham County is not a pauper county ...

... In the two largest schools the high school and grade school pupils are intermingled and in almost constant contact. This deprives the older children of the right to their separate adolescent life undisturbed by the heckling of the smaller ones and because of the tendency of young children to be too much interested in and to ape the activities of the older ones, it deprives the grade school children on their right and need to be simply children ...

... The situation is now intolerable. There is no choice between doing and not doing. The problem must be resolved and solved -- now.

The solution presented was to erect a new central high school, convert both the LaGrange and Crestwood schools into "purely elementary schools," and "rehabilitate" existing schools in LaGrange, Ballardsville, Liberty, Buckner and Crestwood. The LaGrange Training School, an African-American school, would also be rehabilitated with a larger lunchroom. A $190,000 bond issue was suggested to pay for these improvements.

No mention of the Pewee Valley School was made in this first plan, possibly because of the relationship between the school and the church. Katie S. Smith in her 1974 history, "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," noted, "... It became increasingly difficult to get state aid for the school, because it was located on church property." Spending taxpayer money on improvements to a building on property the county didn't own was hard to justify. And the 99-year lease on the property originally negotiated by the Freedmen's Bureau would be up in 1968. The arrangement that initially protected the school during Reconstruction was working against it by the mid-20th century.

No mention of the Pewee Valley School was made in this first plan, possibly because of the relationship between the school and the church. Katie S. Smith in her 1974 history, "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," noted, "... It became increasingly difficult to get state aid for the school, because it was located on church property." Spending taxpayer money on improvements to a building on property the county didn't own was hard to justify. And the 99-year lease on the property originally negotiated by the Freedmen's Bureau would be up in 1968. The arrangement that initially protected the school during Reconstruction was working against it by the mid-20th century.

In May 1949, the Oldham County Board of Education expanded their original building and rehabilitation program when the board:

.... voted to extend the building program it adopted on March 1, 1949 to include the rehabilitation and necessary expansion of all schools, white and colored, in Oldham County and to make this entire program contingent upon a voted bond issue....

...on a motion of Mr. Mount seconded by Mr. Clore and carried the board voted to employ Mr. Elliott Lea of Crestwood, Kentucky to make preliminary plans and estimates on six rooms at LaGrange, two rooms and an auditorium at Crestwood, two rooms and a cistern at Buckner, a two room colored school at Pewee Valley and the repairs necessary to put the present buildings in good condition at Ballardsville, Westport and at the LaGrange Colored School...

To finance their plans, a vote was held in November 1950 on levying a "... Special School Building Tax Rate of not less than five (5) cents nor more than thirty-nine (39) cents on each $100.00 of property subject to local taxation for the purpose of the purchase or lease of school sites and buildings, for the erection and complete equipping of new school buildings, for the major alteration, enlargement and complete equipping of existing buildings, for the purpose of retiring, directly or through rental payments, school revenue bonds issued for the purpose of financing any program for the acquisition, improvement or building of schools?"

Of the 2,057 Oldham Countians who voted on the levy, 1,181 (57 percent) were in favor.

.... voted to extend the building program it adopted on March 1, 1949 to include the rehabilitation and necessary expansion of all schools, white and colored, in Oldham County and to make this entire program contingent upon a voted bond issue....

...on a motion of Mr. Mount seconded by Mr. Clore and carried the board voted to employ Mr. Elliott Lea of Crestwood, Kentucky to make preliminary plans and estimates on six rooms at LaGrange, two rooms and an auditorium at Crestwood, two rooms and a cistern at Buckner, a two room colored school at Pewee Valley and the repairs necessary to put the present buildings in good condition at Ballardsville, Westport and at the LaGrange Colored School...

To finance their plans, a vote was held in November 1950 on levying a "... Special School Building Tax Rate of not less than five (5) cents nor more than thirty-nine (39) cents on each $100.00 of property subject to local taxation for the purpose of the purchase or lease of school sites and buildings, for the erection and complete equipping of new school buildings, for the major alteration, enlargement and complete equipping of existing buildings, for the purpose of retiring, directly or through rental payments, school revenue bonds issued for the purpose of financing any program for the acquisition, improvement or building of schools?"

Of the 2,057 Oldham Countians who voted on the levy, 1,181 (57 percent) were in favor.

Pewee Valley Colored School Building ca. 1951, Courtesy of the Oldham County Historical Society

Groundwork for constructing a new Pewee Valley School was laid a few months before the school bond levy passed. On September 26, 1950, the board bought two acres from R.T. (Ray) Wheeler and Christine Walker about a quarter mile from the old school at what is now Old Floydsburg Road and Ash Avenue. Construction bids were let shortly thereafter, but apparently there were few takers. The minutes for the board of education's November 7, 1950, meeting noted:

On a motion by Mr. Head seconded by Mr. Hammond and unanimously carried the board voted to re-advertized (sic) for bids on the Pewee Valley Colored School. Bids will be opened at 9 a.m. November 21st. The board reserves the right to reject any or all bids.

Based on meeting minutes showing when the board approved insuring the building, the replacement facility appears to have opened in 1952. The first eighth grade class to graduate from the new building included:

John Raymond Hamblin

Raymond Edward Johnson

Gertrude M. Berry

Mary Lou Calloway

Named an Oldham County Living Treasure by the Oldham County Historical Society in 2017, Shirley Edward Hinkle, who was born in 1951 and grew up in the Pewee Valley area, attended the Ash Avenue school before it closed. He went on to graduate from Oldham County High School. He shared his memories of Pewee Valley School in a phone interview on March 28, 2018:

"It was a nice structure ... Instead of a wood stove, we had a furnace ... There were two classrooms, one for grades 1-4 and one for grades 4-8. There was a chalkboard in the middle that was raised up for assemblies and meetings to make one big room ... Each row was a different grade ...

"In black schools, the teachers were strict ... Those black teachers didn't spare the rod. When the schools were integrated, the black kids were afraid to ask and answer questions. We were quiet, but I guess that teaching four different grades, the teachers had to be strict ... The teachers I remember were Mrs. Gilbert and Mrs. Johnson. They replaced Mrs. Gilbert with Mrs. Miller when she died. Mrs. Gilbert had a Master's degree. That was a major accomplishment back then ...

We used to go up to the Lincoln Institute (editor's note: the black high school) in Shelby County for May Day. It was like going to a college campus. People boarded there ... They had a homecoming queen and parade with people driving around in convertibles and record hops and a maypole. Everybody loved it..."

In the Oldham County Living Treasures interview conducted by Nancy Theiss, executive director of the Oldham County Historical Society, Hinkle also recalled:

There was a little cafeteria where we got hot lunches at the Pewee Valley school. We had a cook that cooked everyday. It was funny that people who ate there got free lunch. There was indoor plumbing.

On a motion by Mr. Head seconded by Mr. Hammond and unanimously carried the board voted to re-advertized (sic) for bids on the Pewee Valley Colored School. Bids will be opened at 9 a.m. November 21st. The board reserves the right to reject any or all bids.

Based on meeting minutes showing when the board approved insuring the building, the replacement facility appears to have opened in 1952. The first eighth grade class to graduate from the new building included:

John Raymond Hamblin

Raymond Edward Johnson

Gertrude M. Berry

Mary Lou Calloway

Named an Oldham County Living Treasure by the Oldham County Historical Society in 2017, Shirley Edward Hinkle, who was born in 1951 and grew up in the Pewee Valley area, attended the Ash Avenue school before it closed. He went on to graduate from Oldham County High School. He shared his memories of Pewee Valley School in a phone interview on March 28, 2018:

"It was a nice structure ... Instead of a wood stove, we had a furnace ... There were two classrooms, one for grades 1-4 and one for grades 4-8. There was a chalkboard in the middle that was raised up for assemblies and meetings to make one big room ... Each row was a different grade ...

"In black schools, the teachers were strict ... Those black teachers didn't spare the rod. When the schools were integrated, the black kids were afraid to ask and answer questions. We were quiet, but I guess that teaching four different grades, the teachers had to be strict ... The teachers I remember were Mrs. Gilbert and Mrs. Johnson. They replaced Mrs. Gilbert with Mrs. Miller when she died. Mrs. Gilbert had a Master's degree. That was a major accomplishment back then ...

We used to go up to the Lincoln Institute (editor's note: the black high school) in Shelby County for May Day. It was like going to a college campus. People boarded there ... They had a homecoming queen and parade with people driving around in convertibles and record hops and a maypole. Everybody loved it..."

In the Oldham County Living Treasures interview conducted by Nancy Theiss, executive director of the Oldham County Historical Society, Hinkle also recalled:

There was a little cafeteria where we got hot lunches at the Pewee Valley school. We had a cook that cooked everyday. It was funny that people who ate there got free lunch. There was indoor plumbing.

Interior Photos of the Pewee Valley Colored School on Ash Avenue, Courtesy of the Oldham County Historical Society

The church rented out the old school on their campus after the new school opened. Garland Durham, Jr., and his family lived there for awhile, before the building was demolished. His son, Greg, vaguely remembers the building and church's campus at that time:

All I can remember is the outside was white and there was a little front porch with a concrete stoop maybe five-feet long and two or three-feet wide. When we lived there, I was four or five years old. We sat out there evenings. I played out on the porch, climbing on the poles ... There were three separate buildings on the property -- the church, a concrete block building the Boy Scouts built, and the old school ... There was a pump out there for years ... I remember playing in the yard in a big yellow clay pile ...

All I can remember is the outside was white and there was a little front porch with a concrete stoop maybe five-feet long and two or three-feet wide. When we lived there, I was four or five years old. We sat out there evenings. I played out on the porch, climbing on the poles ... There were three separate buildings on the property -- the church, a concrete block building the Boy Scouts built, and the old school ... There was a pump out there for years ... I remember playing in the yard in a big yellow clay pile ...

The new school, at 331 Ash Avenue, remained in operation until Oldham County Schools were integrated in 1963. By that time, only two schools for the county's African American children remained open. Threats of a lawsuit may have spurred the decision to close down the colored schools and fully integrate. The October 7, 1962 Courier-Journal reported:

Oldham County

To Admit Negroes

In Fall Of 1963

Oldham County School Supt. Alton Ross said Friday Negro students who apply will be accepted next fall in any of his county's public schools.

Ross said this would be no different than the present policy because Negroes have attended two of Oldham County's white elementary schools in recent years and that Negroes have been admitted wherever they apply.

A Louisville Negro attorney, meantime, announced that a group of Negro parents had dropped plans to file suit seeking to force the admission of their children to Oldham schools.

Attorney James Crumlin said the parents had him prepare the legal action after they tried unsuccessfully to have their children transferred from the Negro school at Pewee Valley to Crestwood Elementary School.

Ross said the request was denied because it was made after the school year began.

Oldham County

To Admit Negroes

In Fall Of 1963

Oldham County School Supt. Alton Ross said Friday Negro students who apply will be accepted next fall in any of his county's public schools.

Ross said this would be no different than the present policy because Negroes have attended two of Oldham County's white elementary schools in recent years and that Negroes have been admitted wherever they apply.

A Louisville Negro attorney, meantime, announced that a group of Negro parents had dropped plans to file suit seeking to force the admission of their children to Oldham schools.

Attorney James Crumlin said the parents had him prepare the legal action after they tried unsuccessfully to have their children transferred from the Negro school at Pewee Valley to Crestwood Elementary School.

Ross said the request was denied because it was made after the school year began.

The Oldham County Board of Education's meeting minutes for February 5, 1963, noted:

After considerable discussion based on studies and surveys made by the superintendent a motion was made by Mr. Clore seconded by Mr. Hanna to integrate the Pewee Valley School with the Crestwood Elementary School and that the LaGrange Training School will be integrated with the LaGrange Elementary School. Also, that the Negro high school children be integrated with the Oldham County High School to become effective September 1963.

Pewee Valley School's last graduating eighth grade class included:

Sandra Diane Bridwell

Joseph Scott Hinkle

Theodore Johnson

Lawrence McGee

James Henry Sanders

Charles Emanuel Smyser

It seems fitting that a Bridwell -- a descendant of schoolteacher Romania Booker Cozzens Flournoy's daughter Louise -- was among the last graduates of the school where Mrs. Flournoy spent at least eight years teaching local children their letters.

After considerable discussion based on studies and surveys made by the superintendent a motion was made by Mr. Clore seconded by Mr. Hanna to integrate the Pewee Valley School with the Crestwood Elementary School and that the LaGrange Training School will be integrated with the LaGrange Elementary School. Also, that the Negro high school children be integrated with the Oldham County High School to become effective September 1963.

Pewee Valley School's last graduating eighth grade class included:

Sandra Diane Bridwell

Joseph Scott Hinkle

Theodore Johnson

Lawrence McGee

James Henry Sanders

Charles Emanuel Smyser

It seems fitting that a Bridwell -- a descendant of schoolteacher Romania Booker Cozzens Flournoy's daughter Louise -- was among the last graduates of the school where Mrs. Flournoy spent at least eight years teaching local children their letters.

The Pewee Valley Baptist Church in 1974 and Today

The school was leased for a time by the Pewee Valley Woman's Club for use as a kindergarten and nursery school. The December 8, 1963 Courier-Journal reported:

The Pewee Valley Woman's Club, which has been sponsoring a kindergarten since 1955, is hoping to add a nursery school for 3- and 4-year-olds to its projects in January.

The new class will be housed with the kindergarten in a two-classroom school in Pewee Valley, on Highway 362.

The kindergarten had been using a room in the Crestwood Elementary School until last September. When the Negro school at Pewee Valley was integrated into Crestwood School at that time, the increase in enrollment caused their club to search for new quarters for their kindergarten. The women found what they were looking for in the vacated Negro school in Pewee Valley.

The club members rolled up their sleeves for the task of cleaning, painting and generally fixing up the building.

Now leasing the school, they have an option and want to buy the schoolhouse, which has two classrooms, a kitchen. and two acres with an equipped playground ....

The Pewee Valley Woman's Club, which has been sponsoring a kindergarten since 1955, is hoping to add a nursery school for 3- and 4-year-olds to its projects in January.

The new class will be housed with the kindergarten in a two-classroom school in Pewee Valley, on Highway 362.