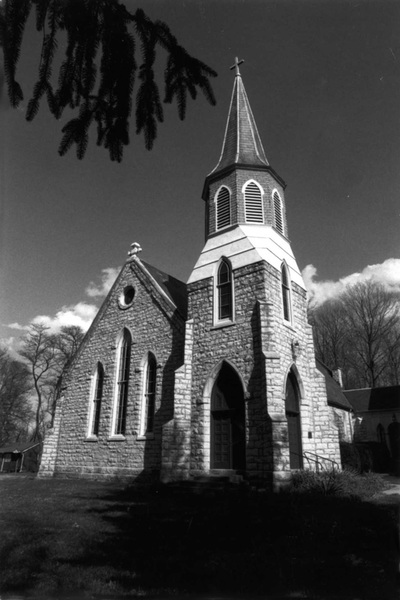

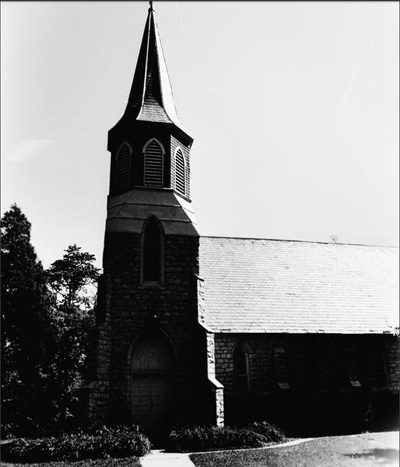

St James Episcopal Church

St. James Episcopal Church Photos from "Historic Pewee Valley," published by Historic Pewee Valley, Inc. in 1991

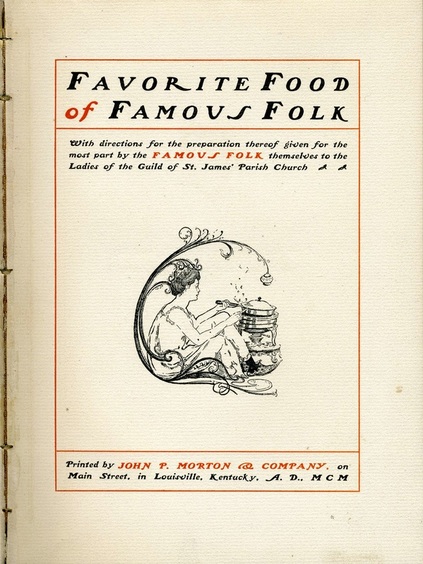

Favorite Food of Famous Folk Cookbook

In 1900, the St. James Ladies Guild staged a fundraising coup with their publication of "Favorite Food of Famous Folk." It was an instant success. The introduction provides a humorous history of how the project got started:

THE spirits of The Guild were low. So were its funds. Green Teas and Variegated Cake Sales had palled on the village public. Also the husbands of The Guild had declined to longer pay for the privilege of eating the provender of their own pantries, set forth in the name of The Guild.

Therefore The Guild counted its pennies and sighed. The slates were dropping from the roof of St. James' as fast as the nuts from the hickories in the wood next the churchyard. The Guild was not to blame that it and its little stone church were growing old and poor together. And as one grows old, to have no rector for lack of money, is sad.

Then the Scheming Member of The Guild suggested a plan. She was a recent comer, and she was younger. If the Scheming Member had been a man, she would have been a promoter.

At her proposal The Guild hesitated. They were not progressive spirits, the members of this Guild. They lived a simple, quiet, village life. And the Scheming Member had a way which made them wonder, after things were over, if there had been an undignified acceleration of pace in some of the movements she led them into.

But the furnace pipes had rusted, and the crimson mantle of the Virginia creeper clambering the gray stones could not conceal that the walls of St. James' needed repointing. Therefore the Scheming Member prevailed, and, urged by her driving energy, The Guild labored faithfully during the winter of '97-'98. Letters something after this fashion were sent out:

"To the half-dozen country women who write this, and who may not hope to ever know the pleasure of exercising the privileges which come with fame, it seems a wonderful and a gracious thing to be able to give, by the weight one's name carries, what can be of such value to others.

"The gift we ask of you is this : We want a recipe, some favorite with you, of any thing, whether edible or drinkable, with the accorded privilegeof using your name with the same.

"Our need for it is this: In lieu of the ability to give largely themselves, a few women, members of The Guild of St. James' Parish, Pewee Valley, Ky., are trying to bring energy to the rescue of their Church, which can afford no rector because of the poorness of its country congregation.

"It is the hope of these ladies constituting The Guild to make sufficient money to build a rectory. A home for a minister secured, the revenues of the Church would be sufficient to support a clergyman.

"The purpose of The Guild, therefore, is to compile a cookery book, a book of favorite dishes of various prominent people, men and women famous in their several ways; and in asking for recipes from such they beg the right to use the name of the person giving it with the recipe.

"If the mouse in its obscurity ever does aught in its small way, by appreciation and admiration and humble applause for those greater, will not the lion, generous in proportion to his biggerness, make these few timid country mice happy, as well as awed, by the magnanimity and promptness of a reply?

• • And it is so little of a roar they ask for, yet so much to them — the recipe for that dish most toothsome to the royal palate, with the weight the royal name attached to it will give."

Something after this fashion The Guild penned its requests. But it took postage, and The Guild lacked the faith* of its new member. So, having written and sent a few tentative letters, it waited.

And in its leisure its members took walks to the postoffice. But if by chance the members met, there was no mention of any special motive actuating this sudden interest in the hours for arriving mail.

It came. The first answer. She had complied. She had also returned the postage sent for her reply. She was, she is, Mrs. Harriet Prescott Spofford.

The Guild called a meeting in haste. One member wept. The Guild saw success, prosperity, ahead. The door opened. The post-mistress had sent two newly-arrived missives.

The first was from one of the heads of a wellknown organization for young girls. She stated that she "knew nothing about cooking." She "had no recipe." She enclosed a small tract. Its title was "Gifts." And this is true.

The other was a letter in compliance. It was from Mr. Edward Everett Hale. This was the forerunner of others.

The Guild grew to rejoice in a sense of humor. With scarcely an exception the letters in compliance abounded with it. So charming are many of the replies accompanying the recipes, The Guild all want them, for heirlooms.

The Guild hopes its public has a sense of humor. If so, its book will have its day, and St. James' its rectory,' and perchance its repointing. The Guild is sanguine. It has day-dreams of a future.

Published in 1900, Favorite Food of Famous Folk was a huge success for the ladies' Guild at St. James Episcopal Church. Image courtesy of Helena Grimes Gleason.

Published in 1900, Favorite Food of Famous Folk was a huge success for the ladies' Guild at St. James Episcopal Church. Image courtesy of Helena Grimes Gleason.

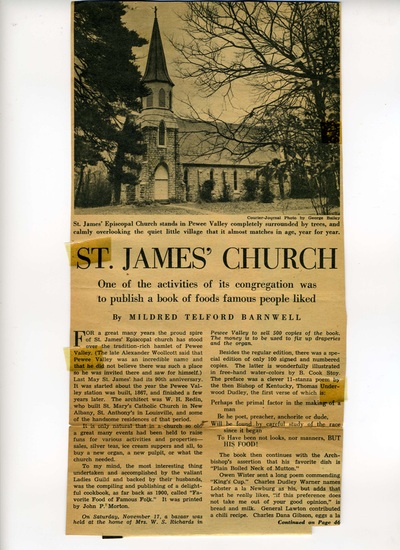

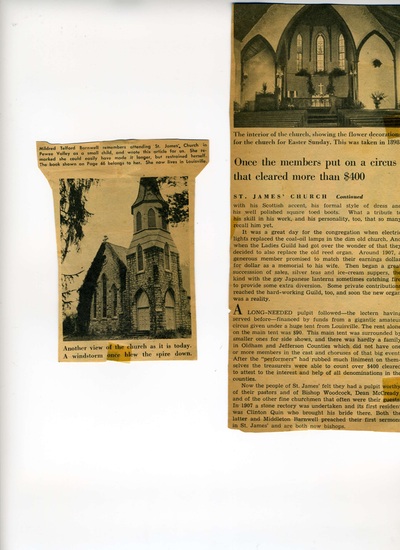

This article from February 9, 1901 Courier-Journal, titled "Louisville Artists to Rival the Roycrofters," describes the limited-edition, hand-illuminated version of the cookbook that was published later:

The little church of St. James, Pewee Valley, has immortalized itself by compiling one of the most unique volumes ever published. "Favorite Food of Famous Folk" was so enthusiastically received by an admiring public that it is to be regretted that only a favored few can have access to the second edition.

It is limited to one hundred copies. It is hand-illumed and illustrated by Miss Mary Gardner Johnson, of Pewee Valley, and Miss B. Cook Stoy, of Louisville. Some of the pages are as elaborately illumed as the missals of old monks, and the dainty marginal sketches rival any work done by the Roycrofters (editor's note: According to Wikipedia, Roycroft was a reformist community of craft workers and artists which formed part of the Arts and Crafts movement in the U.S.).

One of the books that Miss Johnston has recently completed bears two torches on the page that contains the Shakespearean warning, "Tonight thou shalt have cramps" and "Of such stuff dreams are made." Out of the wreaths of smoke uniting at the top of the page the shadowy dream-face of a hobgoblin. Above the introduction is a charming little water-color sketch of the Tower of St. James and its adjacent tree tops. Edward Everett Hale's recipe for clam soup has a tiny marine view of a tailpiece. But the distinctive feature of the book is the shadowy design in colors across the printed page. The flag is draped through Gen. Lawton's recipe for Chili-con-carne. A bouquet of roses is laid across Julia Marlowe's page, and a fan and opera glasses swing from the initial letter which introduces Viola Allen's silver pudding. Bishop Whipple's camp-fire menu shows the camp fire itself and the big kettle swung across his savory suggestions for a picnic dinner.

The little church of St. James, Pewee Valley, has immortalized itself by compiling one of the most unique volumes ever published. "Favorite Food of Famous Folk" was so enthusiastically received by an admiring public that it is to be regretted that only a favored few can have access to the second edition.

It is limited to one hundred copies. It is hand-illumed and illustrated by Miss Mary Gardner Johnson, of Pewee Valley, and Miss B. Cook Stoy, of Louisville. Some of the pages are as elaborately illumed as the missals of old monks, and the dainty marginal sketches rival any work done by the Roycrofters (editor's note: According to Wikipedia, Roycroft was a reformist community of craft workers and artists which formed part of the Arts and Crafts movement in the U.S.).

One of the books that Miss Johnston has recently completed bears two torches on the page that contains the Shakespearean warning, "Tonight thou shalt have cramps" and "Of such stuff dreams are made." Out of the wreaths of smoke uniting at the top of the page the shadowy dream-face of a hobgoblin. Above the introduction is a charming little water-color sketch of the Tower of St. James and its adjacent tree tops. Edward Everett Hale's recipe for clam soup has a tiny marine view of a tailpiece. But the distinctive feature of the book is the shadowy design in colors across the printed page. The flag is draped through Gen. Lawton's recipe for Chili-con-carne. A bouquet of roses is laid across Julia Marlowe's page, and a fan and opera glasses swing from the initial letter which introduces Viola Allen's silver pudding. Bishop Whipple's camp-fire menu shows the camp fire itself and the big kettle swung across his savory suggestions for a picnic dinner.

St. James Episcopal Church illustration by Mary G. Johnston from "Ole Mammy's Torment."

St. James Episcopal Church illustration by Mary G. Johnston from "Ole Mammy's Torment."

Perhaps one of the best is Owen Wiser's "King's Cup." Across the verse that sings of "vine-clad memory" is faintly outlined a bunch of royal purple grapes, with their green leaves and tendrils. No two books in the edition are alike. Sometimes it may be Frank Stockton's page which receives the most attention, with its original dish of "cold pink." Sometimes it may be F. Hopkinson Smith's, with his "new sensation" made of cucumbers and ice. But whether it be the strawberries of the Countess of Aberdeen or the "rabbit and hare" of our own James Lane Allen, each page is a delight. Miss Johnston has certainly interpreted the vagaries of these famous folk with that fine artistic feeling, as well as execution, which appeals irresistibly to book lovers.

Miss Johnston, who is doing one-half the edition, is the daughter of Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, the writer of juvenile books. Miss Johnston illustrated one of her books, "Old (sic) Mammy's Torment." Hers is the illustration of St. James in that book. The toll gate was sketched near Pewee Valley, and the original of "Marse Nat Chadwick" lives at Floydsburg, a little way up the pike.

Miss Stoy is well known in Louisville. She has been the instructor of the Alumnae Club's drawing classes, and designed the headings of the departments in the new magazine "The Arrowhead."

Miss Johnston, who is doing one-half the edition, is the daughter of Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, the writer of juvenile books. Miss Johnston illustrated one of her books, "Old (sic) Mammy's Torment." Hers is the illustration of St. James in that book. The toll gate was sketched near Pewee Valley, and the original of "Marse Nat Chadwick" lives at Floydsburg, a little way up the pike.

Miss Stoy is well known in Louisville. She has been the instructor of the Alumnae Club's drawing classes, and designed the headings of the departments in the new magazine "The Arrowhead."

Photos from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination, 1989

A LEGACY THAT WILL LIVE ON

By Rick Allen May 11, 1993 Washington PostIn 1985 the Rev. K. Logan Jackson and his wife shocked their Episcopal parish in Pewee Valley, Ky., when, with no plans, they announced they would leave in a week to devote their lives to helping children.

The Jacksons ended up in the District, where they began Exodus Youth Services. Operating from a 29-foot van, Logan Jackson dispensed bagels and blankets and looked for ways to get runaways, homeless kids and teenage prostitutes off the streets.

Now, after years spent helping youngsters find fuller lives, Jackson, 43, is preparing for the end of his own. Four years after Exodus began, doctors told Jackson he would die from Lou Gehrig's disease. Gradual paralysis would precede his final suffocation.

"I was so torn up" when his disease was diagnosed, recalled his wife, Mary Lyman Jackson. "I begged the Lord to heal Logan. The Lord said, 'I am healing him, but not in a way which you can see.' "

But Logan Jackson remembered a different reaction. He speaks quietly, searching for air to form his sentences. It is a wispy, private voice. The vocal range of a preacher in a pulpit is gone.

"A tremendous . . . peace just filled my heart. The Lord said to me that 'the richest time in your ministry is ahead.' " Jackson paused. "He said, 'Stay concentrated on the power of the cross.' "

Once a commanding presence on the street at 6 feet 1 inch and 220 pounds, Jackson took to praying silently in a wheelchair beside the van. Now that his weight has dropped by nearly half and his limbs are useless, his wife has taken over the Exodus operations, and he works at their Gaithersburg home.

"I'm not as picky . . . about how I pray and where," he said. "Offering up prayer is my work."

Logan Jackson was a popular rector at St. James in Pewee Valley, a wealthy suburb of Louisville. One night, praying alone in the church, he said, he got a strong sense that he should spend his life helping children who "are wounded and in tremendous pain."

Jackson went straight to the rectory to talk to his wife, who was putting their three children to bed.

"Okay. Let's pack," she said.

For the next eight months, they lived in an abandoned convent in Sewanee, Tenn., planning the next move.

"It was wild, let me tell you. Our parents thought we just had a midlife crisis. The bishop thought we needed psychiatric counseling," Mary Lyman recalls in her broad Georgia accent.

Logan went to Washington to look for others who recognized the urgent national need for a children's advocacy program. After attending hearings by the attorney general's Commission on Pornography about the dangers faced by runaway children in big cities he visited programs for runaways across the country and decided on a van-based health service in Washington.

"We were working to get a person from the street to the {Sasha Bruce} shelter {in Northeast}. Our focus . . . was meeting the immediate and external needs, not concentrating on the spiritual," he said. "It was a watered-down approach to dealing with the real issues of pain on the street."

But Logan Jackson and the Exodus van, called Streetside, were credited with filling a void that had been highlighted by the 1986 D.C. Task Force on Homeless and Runaway Youth. Homeless or troubled youngsters involved with alcohol, drugs or prostitution confided in Jackson. Those who lived in violent neighborhoods would run to meet "the church van" to tell him their stories.

In 1990, Jackson began having neck problems that made it hard to walk. Surgery and physical therapy did nothing, and doctors at Georgetown University Hospital diagnosed Lou Gehrig's disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which destroys nerves that control muscle movement.

As they coped with the news, the Jacksons made a pilgrimage to a shrine in Yugoslavia and then sought the support of an ecumenical charismatic community in Gaithersburg, joining the Mother of God's weekly prayer meetings.

"The Lord has a marvelous sense of humor that he should call me to this charismatic community," Jackson said. "Everybody gathers, raises their hands up, and praises God with shouts and all kinds of noise. And I am stricken with this disease which does not allow me to project my voice or raise my arms.

"You can't be a charismatic without praying for a miracle," Jackson said. "And it's not easy if you don't get 'em: What's wrong with you? Are you weak of faith?"

The miracle the Jacksons prayed for seemed to come in April 1991.

Logan Jackson grew strong enough to stand up and preach for 45 minutes at a time. He could drive a car again, hug his wife. He even started working out at a health club. "We all thought -- and some of the doctors thought, but not all of them -- that it was the first remission in the history of Lou Gehrig's disease," Jackson recalled.

But no sooner were Exodus newsletters sent out proclaiming Jackson's good news than his health began to decline again. "Fool for Christ," Jackson said, smiling.

At home, there have been a few of what Mary Lyman calls "nurses from hell" -- the ones who dropped Logan on the floor or let him go hungry -- in a succession of people hired to care for him when his wife is busy with Exodus or family matters.

There have been plenty of those times lately. The family's ancient Welsh corgi, Wee Bee, is suffering paralyzed hind legs, and a tiny wheeled cart -- a sort of doggie wheelchair -- is due to arrive any day. "The only problem is that if you leave the door open to the basement stairs, Wee Bee can go flying down. . . . So you have to kind of close all the doors," Mary Lyman said.

And the Jacksons' daughter, Kemper, 11, is being treated for Lyme disease, a tick-borne ailment that causes joint pain and blurry vision.

"There's a side that's pretty rough. But then there's this side you have to laugh at. My dad's paralyzed, the dog's paralyzed, I've got this disease, and my mom's got everything on her shoulders. So we kind of laugh," Kemper said.

But Walter, 9, the youngest Jackson, misses the days when his father threw him in the air in their hide-and-seek game called buggedy-boo. They used to play football too, Walter said.

"You were the football, kid," his father reminded him.

The oldest Jackson child, Mercer, 12, is more reserved. "They talk to my mom . . . they're more open," he said of his younger siblings. "Sometimes I feel bad, but I don't express it."

Until recently, Logan Jackson continued to join Exodus street counselors on their weekly rounds in Adams-Morgan or on 24th Street NE or Bruce Place SE. Now each day brings another friend, another relative, to his house for a quiet visit.

Under Mary Lyman's influence, Exodus increasingly works with "latchkey children" from single-parent families. Its 29 counselors also visit homes in a dozen other areas, serving a total of 772 clients, some by telephone and mail.

By Rick Allen May 11, 1993 Washington PostIn 1985 the Rev. K. Logan Jackson and his wife shocked their Episcopal parish in Pewee Valley, Ky., when, with no plans, they announced they would leave in a week to devote their lives to helping children.

The Jacksons ended up in the District, where they began Exodus Youth Services. Operating from a 29-foot van, Logan Jackson dispensed bagels and blankets and looked for ways to get runaways, homeless kids and teenage prostitutes off the streets.

Now, after years spent helping youngsters find fuller lives, Jackson, 43, is preparing for the end of his own. Four years after Exodus began, doctors told Jackson he would die from Lou Gehrig's disease. Gradual paralysis would precede his final suffocation.

"I was so torn up" when his disease was diagnosed, recalled his wife, Mary Lyman Jackson. "I begged the Lord to heal Logan. The Lord said, 'I am healing him, but not in a way which you can see.' "

But Logan Jackson remembered a different reaction. He speaks quietly, searching for air to form his sentences. It is a wispy, private voice. The vocal range of a preacher in a pulpit is gone.

"A tremendous . . . peace just filled my heart. The Lord said to me that 'the richest time in your ministry is ahead.' " Jackson paused. "He said, 'Stay concentrated on the power of the cross.' "

Once a commanding presence on the street at 6 feet 1 inch and 220 pounds, Jackson took to praying silently in a wheelchair beside the van. Now that his weight has dropped by nearly half and his limbs are useless, his wife has taken over the Exodus operations, and he works at their Gaithersburg home.

"I'm not as picky . . . about how I pray and where," he said. "Offering up prayer is my work."

Logan Jackson was a popular rector at St. James in Pewee Valley, a wealthy suburb of Louisville. One night, praying alone in the church, he said, he got a strong sense that he should spend his life helping children who "are wounded and in tremendous pain."

Jackson went straight to the rectory to talk to his wife, who was putting their three children to bed.

"Okay. Let's pack," she said.

For the next eight months, they lived in an abandoned convent in Sewanee, Tenn., planning the next move.

"It was wild, let me tell you. Our parents thought we just had a midlife crisis. The bishop thought we needed psychiatric counseling," Mary Lyman recalls in her broad Georgia accent.

Logan went to Washington to look for others who recognized the urgent national need for a children's advocacy program. After attending hearings by the attorney general's Commission on Pornography about the dangers faced by runaway children in big cities he visited programs for runaways across the country and decided on a van-based health service in Washington.

"We were working to get a person from the street to the {Sasha Bruce} shelter {in Northeast}. Our focus . . . was meeting the immediate and external needs, not concentrating on the spiritual," he said. "It was a watered-down approach to dealing with the real issues of pain on the street."

But Logan Jackson and the Exodus van, called Streetside, were credited with filling a void that had been highlighted by the 1986 D.C. Task Force on Homeless and Runaway Youth. Homeless or troubled youngsters involved with alcohol, drugs or prostitution confided in Jackson. Those who lived in violent neighborhoods would run to meet "the church van" to tell him their stories.

In 1990, Jackson began having neck problems that made it hard to walk. Surgery and physical therapy did nothing, and doctors at Georgetown University Hospital diagnosed Lou Gehrig's disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, which destroys nerves that control muscle movement.

As they coped with the news, the Jacksons made a pilgrimage to a shrine in Yugoslavia and then sought the support of an ecumenical charismatic community in Gaithersburg, joining the Mother of God's weekly prayer meetings.

"The Lord has a marvelous sense of humor that he should call me to this charismatic community," Jackson said. "Everybody gathers, raises their hands up, and praises God with shouts and all kinds of noise. And I am stricken with this disease which does not allow me to project my voice or raise my arms.

"You can't be a charismatic without praying for a miracle," Jackson said. "And it's not easy if you don't get 'em: What's wrong with you? Are you weak of faith?"

The miracle the Jacksons prayed for seemed to come in April 1991.

Logan Jackson grew strong enough to stand up and preach for 45 minutes at a time. He could drive a car again, hug his wife. He even started working out at a health club. "We all thought -- and some of the doctors thought, but not all of them -- that it was the first remission in the history of Lou Gehrig's disease," Jackson recalled.

But no sooner were Exodus newsletters sent out proclaiming Jackson's good news than his health began to decline again. "Fool for Christ," Jackson said, smiling.

At home, there have been a few of what Mary Lyman calls "nurses from hell" -- the ones who dropped Logan on the floor or let him go hungry -- in a succession of people hired to care for him when his wife is busy with Exodus or family matters.

There have been plenty of those times lately. The family's ancient Welsh corgi, Wee Bee, is suffering paralyzed hind legs, and a tiny wheeled cart -- a sort of doggie wheelchair -- is due to arrive any day. "The only problem is that if you leave the door open to the basement stairs, Wee Bee can go flying down. . . . So you have to kind of close all the doors," Mary Lyman said.

And the Jacksons' daughter, Kemper, 11, is being treated for Lyme disease, a tick-borne ailment that causes joint pain and blurry vision.

"There's a side that's pretty rough. But then there's this side you have to laugh at. My dad's paralyzed, the dog's paralyzed, I've got this disease, and my mom's got everything on her shoulders. So we kind of laugh," Kemper said.

But Walter, 9, the youngest Jackson, misses the days when his father threw him in the air in their hide-and-seek game called buggedy-boo. They used to play football too, Walter said.

"You were the football, kid," his father reminded him.

The oldest Jackson child, Mercer, 12, is more reserved. "They talk to my mom . . . they're more open," he said of his younger siblings. "Sometimes I feel bad, but I don't express it."

Until recently, Logan Jackson continued to join Exodus street counselors on their weekly rounds in Adams-Morgan or on 24th Street NE or Bruce Place SE. Now each day brings another friend, another relative, to his house for a quiet visit.

Under Mary Lyman's influence, Exodus increasingly works with "latchkey children" from single-parent families. Its 29 counselors also visit homes in a dozen other areas, serving a total of 772 clients, some by telephone and mail.

Related Links: