Maple Nook/Undulata / Fern Rock Cottage /

The Haunted House of Hartwell Hollow

Central Place Subdivision was once the site of one of Pewee Valley's first homes. Half a century later, home that inspired the Haunted House of Hartwell Hollow in Annie Fellows Johnston’s novel, “The Little Colonel’s Holidays.”

The Miller Years (1850-53): Maple Nook

The house was built of logs about 1850 by James Alexander Miller (1815-1900), a partner in Miller, Wingate & Company, an agricultural implement manufacturer in Louisville. Miller and his wife, Mary Crews Talbot Brown, first spied the land while visiting artist William C. Allan, who was already living in what was then a relatively inaccessible part of Oldham County, south of the established settlement of Rollington and the Ballardsville Turnpike- Boonesboro Road.

Excerpts from his notebook, describing the settlement of Pewee Valley and the role the Millers played in attracting an elite group of literati to the new town, were provided to the Pewee Valley Centennial Commission by Isabelle Anderson, a descendant of James S. Lyman, early member of the Town Council, who married Mary Emily Miller, James Alexander Miller's daughter:

There lived in the old farm house on the hill beyond the village of Rollington in Oldham County, Ky. Mr. & Mrs. Wm. C. Allan, who inherited the old farm of some 60 acres or more from his father. Mr. Allan was an artist of considerable taste and culture. Mrs. Allan was from South Carolina, a very handsome brunette, & was highly cultivated and accomplished in music.

An intimacy grew between the Allans & the families of Mr. & Mrs. James A. Miller, Prof. Noble Butler, & Thomas H. Shreve and family of Louisville.

In the Spring of 1848, Mr. Hugh Wilkins of Louisville purchased at public sale at LaGrange, Ky. 160 acres of land at $5 an acre immediately adjoining the Allan tract.

One Saturday afternoon in the Fall of 1848, Mr. & Mrs. Miller drove out to visit the Allans & spend Sunday. The day following was lovely & in general was indulged in.

The result of which was the purchase by Mr. Miller on Monday morning of 40 acres at $20 per acre, on which he built a one story & a half double log home, stable & other improvements, into which the family moved in the Spring of 1850.

This purchase, subsequent improvement & occupancy of our family actually constituted the nucleus & very beginning of what is now known as the far-famed Pewee Valley, Kentucky, the most famous suburb of Louisville.

Immediately upon their removal to their new country home, which they named Maple Nook, frequent visitors from among their extended city friends were made during the following Summer to their hospitable home, which soon resulted in bringing other admirers & purchasers into the Valley.

The earliest of these were Prof. Noble Butler & family who purchased & improved the place now occupied by W.H. Dulaney.

Then W.N. Haldeman who for a time lived in Rollington but subsequently purchased & improved the grounds now known as the Craig place.

Next came Thomas Smith & family who purchased the place now occupied by Judge Muir. Judge Bryant was also a member of Mr. Smith's household. Mrs. Smith was a sister (editor's note: she was actually the niece) of Mrs. Henry Clay, & brought with her the three orphan children, whom she raised, of Henry Clay, Jr., Henry, Thomas & Nannette. The two boys were killed during the Rebellion. Nannette subsequently married Major H.C. McDowell of Louisville, & now own & occupy Ashland, the old homestead of Henry Clay near Lexington, Ky.

Next in order came W.H. Walker & family who bought & improved the place now occupied by the Van Horn family.

Then came Jonas H. Rhorer who bought the Hugh Milkins tract of 120 acres, & his brother Milton Rhorer who built the house near the Station.

Then came Thomas H. Crawford, Ex-Mayor of Louisville, & bought & improved the place now owned & occupied as a Presbyterian School (editor's note: Kentucky College for Young Ladies).

An anecdote from the Allan and Miller years survives in a letter sent to the Editors Drawer at Harper's Magazine (from Harper's Magazine, Volume 32, Henry Mills Alden, Thomas Bucklin Wells, Frederick Lewis Allen, Lee Foster Hartman. published by Harper's Magazine Foundation, 1866, page 816):

We have here a letter from Middletown, Kentucky:

Dear Drawer,—There have been a number of anecdotes lying loose in the Balaam basket of memory, which I have often thought would do to patch Drawers with, and have intended to send them to you, but have neglected it in that careless, putting off way men have.

Yon knew Mr. Allen, the artist, a man of genius and generosity unexcelled. In his lifetime he used to assemble at his house, that overlooks the metropolitan splendors of Rollington, Kentucky, a goodly gathering of guests, who smoked long-handled pipes, made bad puns, asked unanswerable conundrums and in a generally jolly way made much of one another. On one of these occasions Noble Butler, the grammarian, was one of the party, and the artist had placed in his hands, for a subcoenative smoke, a Turkish pipe called a hookah. When it came to the Professor's turn for a conundrum or joke, he drew inspiration from his pipe-stem and bowl, and asked "why that pipe was like a cow?" having in mind the obvious answer that it was a honker. It had to go around the circle by rule and be given up before Mr. Butler could sprinkle his Attic salt; and don't you think Mr. Allen was mean enough to anticipate the propounder, and say the resemblance was "because there was a calf sucking it !" The Professor—one of the best men in the world—paid forfeit, and enjoyed the joke best of all.

We have here a letter from Middletown, Kentucky:

Dear Drawer,—There have been a number of anecdotes lying loose in the Balaam basket of memory, which I have often thought would do to patch Drawers with, and have intended to send them to you, but have neglected it in that careless, putting off way men have.

Yon knew Mr. Allen, the artist, a man of genius and generosity unexcelled. In his lifetime he used to assemble at his house, that overlooks the metropolitan splendors of Rollington, Kentucky, a goodly gathering of guests, who smoked long-handled pipes, made bad puns, asked unanswerable conundrums and in a generally jolly way made much of one another. On one of these occasions Noble Butler, the grammarian, was one of the party, and the artist had placed in his hands, for a subcoenative smoke, a Turkish pipe called a hookah. When it came to the Professor's turn for a conundrum or joke, he drew inspiration from his pipe-stem and bowl, and asked "why that pipe was like a cow?" having in mind the obvious answer that it was a honker. It had to go around the circle by rule and be given up before Mr. Butler could sprinkle his Attic salt; and don't you think Mr. Allen was mean enough to anticipate the propounder, and say the resemblance was "because there was a calf sucking it !" The Professor—one of the best men in the world—paid forfeit, and enjoyed the joke best of all.

The Millers had 10 children, two of which were born while they were living in Undulata:

In about 1857, Miller built a second summer home in Pewee Valley on land adjoining the railroad (Delachoosha on the Little Colonel Gameboard). By the 1870 census, the Millers were living full-time in Pewee Valley and James Miller listed his occupation as "Farmer."

- Sophia (1841–1843) born and died in Louisville

- Susan (1843–1844) born and died in Louisville

- Susan Sue II (1844–1886) born in Louisville

- James Allen (1846–1918) born in Louisville

- Mary Emily (1848–1937) born in Louisville

- Noble Butler (1850–1876) born in Pewee Valley

- Octavia Shreve (1853–1933) born in Pewee Valley

- Madeline (1854–1857) born and died in Louisville

- Robert H. (1856–1857) born and died in Louisville

- Joseph Clayton Talbot (1857–) born in Pewee Valley

In about 1857, Miller built a second summer home in Pewee Valley on land adjoining the railroad (Delachoosha on the Little Colonel Gameboard). By the 1870 census, the Millers were living full-time in Pewee Valley and James Miller listed his occupation as "Farmer."

The Gallagher Years (1852-1884): Undulata and Fern Rock Cottage

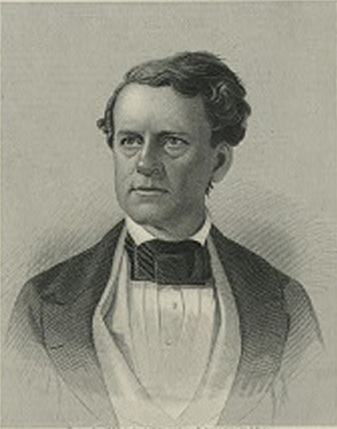

Portrait of William D. Gallagher

Portrait of William D. Gallagher

Poet and journalist William D. Gallagher (August 21, 1808 – June 27, 1884) moved to Miller’s property at what is now the corner of Central Avenue and Peace Lane on January 1, 1853. He’d started in his trade as a typesetter at the tender age of 13, when he was apprenticed to a Cincinnati printer. At age 20, he won his first recognition as a writer through a series of letters he penned about the West while travelling across Kentucky and Mississippi.

In 1831, he became editor of the Cincinnati Mirror, a literary journal. Four years later, he published two small pamphlets of poems titled “Erato No. I.” and “Erato No. II.” Those were followed by “Erato No. III.” in1837, and “The Poetical Literature of the West,” an anthology of Western verse, in 1841. By the time he arrived in Louisville, his resume included editing another literary journal, The Hesperian, and a decade of political coverage for the Cincinnati Gazette.

What brought Gallagher and his family from Ohio to a slave state like Kentucky was an ownership/ editorship opportunity with Walter Newman Haldeman’s Louisville Morning Courier. It proved to be a disaster, both personally and professionally, nipping his promising writing career in the bud and making him the butt of vitriol and violent threats, according to this excerpt from a biography that appeared in “Kentucky in American Letters. Volume 1” by John Wilson Townsend and Dorothy Edwards Townsend (Torch Press, Cedar Rapids, Iowa; 1913):

… In the summer of 1852, Gallagher had an opportunity of going into the New York Tribune with Horace Greeley; and another of taking a one-half interest in the Cincinnati Commercial, then controlled by his friend, M. D. Potter. He was advised and urged by such old anti-slavery friends as Gamaliel Bailey, Thomas H. Shreve, Noble Butler, and others, in Washington, Cincinnati and Louisville, to purchase half the stock of the Louisville Daily Courier, and to assume the editorship of that paper, which was to be a southern organ for the advocacy of Corwin's nomination to the presidency. After long consideration, a decision was reached in favor of the Courier, and Gallagher returned to the West with his family, arriving at Louisville the first day of January, 1853. Nearly thirty years afterward he wrote: "My connection with the Courier proved to be an unfortunate one. There was little sympathy with my editorial tone and teachings, either in Louisville or throughout Kentucky. I worked hard and lost money. So in 1854 I sold my interest in the concern and withdrew from the paper, having been stigmatized again and again, in southern and south-western localities, as an abolition adventurer on the wrong side of the Ohio river, as former president of the underground railroad through Ohio for runaway slaves, etc., etc." Personal animosity was inflamed against the unpopular editor from his boldly attacking John J. Crittenden for consenting to defend Matt. Ward, who killed the young teacher, Butler, in his own school-room. (Editor’s note: the murdered professor, W.H.G. Butler, was a brother of Noble Butler, one of Gallagher's dearest friends.)

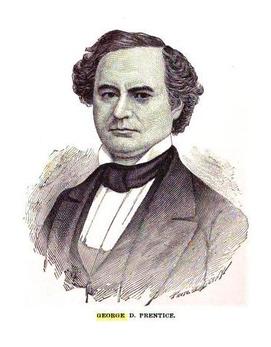

Even George D. Prentice (et tu Brute!) joined in the hue and cry against the Courier editor, partly because Gallagher was an Irish anti-know-nothing, but mainly on the sore question of slavery. Prentice came up to Cincinnati and spent several days looking through the files of the Gazette to find in Gallagher's editorials abolition sentiments that might be used against him in Louisville. An article appeared in the Journal branding Gallagher with the crime of managing the underground railroad. This direct and personal attack roused the Celtic resentment of its subject, and he replied in the editorial columns of the Courier, over his signature, denying the allegation, and closed his card by denouncing the author of the calumny as '* a scoundrel and liar." He had caught the spirit of personal journalism. The consequences were, if not dramatic, at least theatrical.

Upon a day the Louisville train brings to Pewee Valley, in Oldham county, where Mr. Gallagher had bought a little farm, a military gentleman of chivalrous appearance, who inquires the way from the station to Fern Rock Cottage. Finding the house, he knocks, and is admitted to the parlor by a colored servant. The master of the house is indisposed, is resting upon his bed, but clothed and in his right mind, and able to receive his visitor. The military gentleman will wait. To him presently enters William "Dignity" Gallagher, who, recognizing Colonel Churchill, cordially greets him, and asks his pleasure. The colonel, with equal politeness, takes from his pocket a letter, which he hands to the convalescent editor. The missive is opened, and it proves to be a challenge from the proprietor of the Louisville Journal. Gallagher reads, tears the communication into a handful of bits, and throws the fragments on the floor. "Colonel Churchill, tell Mr. Prentice that is my answer to his foolish challenge."

Even George D. Prentice (et tu Brute!) joined in the hue and cry against the Courier editor, partly because Gallagher was an Irish anti-know-nothing, but mainly on the sore question of slavery. Prentice came up to Cincinnati and spent several days looking through the files of the Gazette to find in Gallagher's editorials abolition sentiments that might be used against him in Louisville. An article appeared in the Journal branding Gallagher with the crime of managing the underground railroad. This direct and personal attack roused the Celtic resentment of its subject, and he replied in the editorial columns of the Courier, over his signature, denying the allegation, and closed his card by denouncing the author of the calumny as '* a scoundrel and liar." He had caught the spirit of personal journalism. The consequences were, if not dramatic, at least theatrical.

Upon a day the Louisville train brings to Pewee Valley, in Oldham county, where Mr. Gallagher had bought a little farm, a military gentleman of chivalrous appearance, who inquires the way from the station to Fern Rock Cottage. Finding the house, he knocks, and is admitted to the parlor by a colored servant. The master of the house is indisposed, is resting upon his bed, but clothed and in his right mind, and able to receive his visitor. The military gentleman will wait. To him presently enters William "Dignity" Gallagher, who, recognizing Colonel Churchill, cordially greets him, and asks his pleasure. The colonel, with equal politeness, takes from his pocket a letter, which he hands to the convalescent editor. The missive is opened, and it proves to be a challenge from the proprietor of the Louisville Journal. Gallagher reads, tears the communication into a handful of bits, and throws the fragments on the floor. "Colonel Churchill, tell Mr. Prentice that is my answer to his foolish challenge."

Walter Haldeman

Walter Haldeman

The challenge to duel George Prentice of the Louisville Journal wasn’t the only violence Gallagher met with in Kentucky over his anti-slavery sentiments. In 1860, he was threatened with physical harm by some of his Rebel neighbors in Pewee Valley:

Busied with the labors of peace, Gallagher little anticipated how soon he was to assume important duties of war, not in the capacity of a military man, but as a civil officer of the Government, which he had served so faithfully before. A new President of the United States was to be chosen. He attended several political conventions—one State convention—was a delegate from Kentucky to the National convention at Chicago, in 1860, and was made somewhat conspicuous there by a response which he gave in reply to an address of welcome. Though his personal preference was for Mr. Chase, he went with the current for "Old Abe," working hard and voting for his nomination, against that of William H. Seward; and was one of those who carried the news to Springfield. In these and other public ways, he rendered himself so objectionable to the great mass of the people in his neighborhood, who were opposed to the election of Mr. Lincoln, that a public meeting was called and held within a mile of his house, for the purpose of giving him notice to leave the State. The situation was now dramatic in earnest, and might have become tragic, had it not been for the personal friendship of some of his political opposers. On the day of the threatened violence, Mr. Gallagher had intended to go from his home to Cincinnati.

At Pewee Station, his friend, Mr. Haldeman, called out: "Gallagher, have you seen Dr. Bell?" "No." "He says they are going to mob you; there is a crowd at Beard's Station, and they swear you must leave the State." Dr. Bell came up and advised Gallagher to go on to Cincinnati. "No, gentlemen; if violence is meditated, my family are the first consideration, and home is the place for me. Mr. Crow"—this to the station-keeper—" let it be known that I am at home." Haldeman forced into Gallagher's hand a navy revolver, though the poet had never fired a pistol in his life; another political enemy, but personal friend, gave him a big bowie-knife, and thus grimly over-armed he returned to Fern Rock, to the amazement of his wife and daughters.

The meeting at Beard's Station was a dangerous one, but Gallagher's rebel neighbors, with warm respect for the man and chivalrous regard for fair play, demanded a hearing. A stalwart young mechanic took upon himself to champion the cause of free opinion. "I hate Gallagher's politics as much as any of you," said this gallant Kentuckian to the crowd, " but he has as good a right to his ideas as we have to ours, and "—with a string of terrible oaths—" whoever tries to lay a hand on him, or to give him an order to leave the State, must first pass over my dead body." The notice was not served; but after hours of talk, the assemblage contented itself with providing for the appointment of a "vigilance committee" for the neighborhood and dispersed. The excitement died away, and the Gallagher family lived in comparative safety; the stars and stripes floated above the roof of Fern Rock Cottage during the six gloomy years of the war.

Busied with the labors of peace, Gallagher little anticipated how soon he was to assume important duties of war, not in the capacity of a military man, but as a civil officer of the Government, which he had served so faithfully before. A new President of the United States was to be chosen. He attended several political conventions—one State convention—was a delegate from Kentucky to the National convention at Chicago, in 1860, and was made somewhat conspicuous there by a response which he gave in reply to an address of welcome. Though his personal preference was for Mr. Chase, he went with the current for "Old Abe," working hard and voting for his nomination, against that of William H. Seward; and was one of those who carried the news to Springfield. In these and other public ways, he rendered himself so objectionable to the great mass of the people in his neighborhood, who were opposed to the election of Mr. Lincoln, that a public meeting was called and held within a mile of his house, for the purpose of giving him notice to leave the State. The situation was now dramatic in earnest, and might have become tragic, had it not been for the personal friendship of some of his political opposers. On the day of the threatened violence, Mr. Gallagher had intended to go from his home to Cincinnati.

At Pewee Station, his friend, Mr. Haldeman, called out: "Gallagher, have you seen Dr. Bell?" "No." "He says they are going to mob you; there is a crowd at Beard's Station, and they swear you must leave the State." Dr. Bell came up and advised Gallagher to go on to Cincinnati. "No, gentlemen; if violence is meditated, my family are the first consideration, and home is the place for me. Mr. Crow"—this to the station-keeper—" let it be known that I am at home." Haldeman forced into Gallagher's hand a navy revolver, though the poet had never fired a pistol in his life; another political enemy, but personal friend, gave him a big bowie-knife, and thus grimly over-armed he returned to Fern Rock, to the amazement of his wife and daughters.

The meeting at Beard's Station was a dangerous one, but Gallagher's rebel neighbors, with warm respect for the man and chivalrous regard for fair play, demanded a hearing. A stalwart young mechanic took upon himself to champion the cause of free opinion. "I hate Gallagher's politics as much as any of you," said this gallant Kentuckian to the crowd, " but he has as good a right to his ideas as we have to ours, and "—with a string of terrible oaths—" whoever tries to lay a hand on him, or to give him an order to leave the State, must first pass over my dead body." The notice was not served; but after hours of talk, the assemblage contented itself with providing for the appointment of a "vigilance committee" for the neighborhood and dispersed. The excitement died away, and the Gallagher family lived in comparative safety; the stars and stripes floated above the roof of Fern Rock Cottage during the six gloomy years of the war.

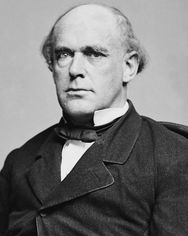

Matthew Brady Portrait of Salmon P. Chase

Matthew Brady Portrait of Salmon P. Chase

During the Civil War itself, political appointments supplemented the meager income Gallagher eked out on his farm. He worked for a time as an assistant to Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, and was selected by President Lincoln as Collector of Customs and special commercial agent for the upper Mississippi Valley, where his main job was to stop provisions and stores from reaching Confederate forces.

In the summer of 1863, he was appointed Surveyor of Customs in Louisville – the job his old partner at the Morning Courier forfeited in 1861 when he joined up in Bowling Green with Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner -- and served as Pension Agent after the war ended.

However, the last years of his life were unkind to him. His wife, Emma, died suddenly of heart disease on December 26, 1867. His friends were unable to secure any political appointments for him and money – or the lack thereof – became a central issue in his life, forcing him to work at a menial clerical position nearly up until the day he died:

The echoes of battle died away and Mr. Gallagher returned to his quiet farm, planted flowers, made rockeries, and planned new buildings…In the reaction that followed the seeming prosperity stimulated by the war, Mr. Gallagher suffered financially, as did thousands of others. His property at Pewee Valley depreciated and he also lost money by unfortunate investments. Driven by necessity he earned his living by spending patient hours at the clerical desk as salaried secretary of the “Kentucky Land Company." In 1881, he was working, as he expressed it, "like a beaver."

When the old poet passed away in 1884, he was being cared for in the family home by his daughters: Emma, Fanny and Jennie Gallagher Cotton. His granddaughter, Sally Cotton, was also living at the home when the 1880 census was taken.

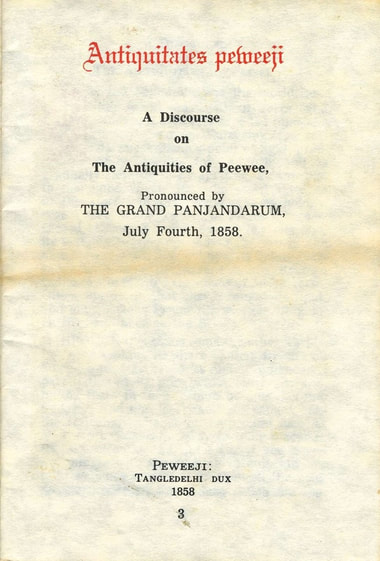

Title page of "Antiquitates peweeji" reprinted as a Christmas card by Eleanor Sedley of Edgewood

Title page of "Antiquitates peweeji" reprinted as a Christmas card by Eleanor Sedley of Edgewood

During Gallagher’s Pewee Valley years, the farm he lived on was known by two names: Undulatta/ Undulata and Fern Rock Cottage. Noble Butler’s July 4, 1858 spoof, “Antiquatates Peweeji,” appointed himself Rex; William (Gallagher) of Undullata, Lord High Chancellor, Edwin (Bryant) of Oaklea, Lord High Chancellor; Benjamin (Cassidy) of Owl’s Nest, Grand Panjandarum; and Thomas (Smith) of Woodside, First Lord of Council of Pewee Valley. Undulata is also the home’s name on the Little Colonel Gameboard. However, Gallagher in later years referred to his property as Fern Rock Cottage. A description of the farm was included in his biography:

Mr. Gallagher's house, a rambling frame cottage, covered with American ivy, was built in the midst of great forest trees—beech, oak, maple, poplar, and a newer growth of sassafras, dogwood, black-haw and evergreens. Gray squirrels barked and skipped about the door-yard, and the cat-bird, the redbird, and the unceremonious blue-jay came near the porches for their daily bread.

Little Colonel Connections: The Haunted House of Hartwell Hollow

By the time Annie Fellows Johnston published “The Little Colonel’s Holidays” in 1901, William Gallagher had been dead about seven years. Fern Rock Cottage must have had an abandoned air during the 1890s when she rented The Gables. This is how she described it in Chapter XI:

NOTHING worse than rats and spiders haunted the old house of Hartwell Hollow, but set far back from the road in a tangle of vines and cedars, it looked lonely and neglected enough to give rise to almost any report. The long unused road, winding among the rockeries from gate to house, was hidden by a rank growth of grass and mullein. From one of the trees beside it an aged grape-vine swung down its long snaky limbs, as if a bunch of giant serpents had been caught up in a writhing mass and left to dangle from tree-top to earth. Cobwebs veiled the windows, and dead leaves had drifted across the porches until they lay knee-keep in some of the corners.

As Miss Allison paused in front of the doorstep with the keys, a snake glided across her path and disappeared in one of the tangled rockeries. Both the coloured women who were with her jumped back, and one screamed.

"It won't hurt you, Sylvia," said Miss Allison, laughingly. "An old poet who owned this place when I was a child made pets of all the snakes, and even brought some up from the woods as he did the wild flowers. That is a perfectly harmless kind."

"Maybe so, honey," said old Sylvia, with a wag of her turbaned head, "but I 'spise 'em all, I sho'ly do. It's a bad sign to meet up wid one right on de do'step. If it wasn't fo' you, Miss Allison, I wouldn't put foot in such a house. An' I tell you p'intedly, what I says is gospel truth, if I ketch sound of a han't, so much as even a rustlin' on de flo', ole Sylvia gwine out'n a windah fo' you kin say scat!

The Blackley Years (ca. 1898-1920)

Adair County News, January 22, 1902

Adair County News, January 22, 1902

The Gregory Taylor Blackley family came to Pewee Valley from Frankfort, Ky., according to the late Tom Murphy, a long-time Pewee Valley resident. In 1892, Blackley was the general manager of the Mason & Foard Co., a Frankfort manufacturer that used convict labor from the Kentucky Penitentiary. The March 20, 1889 Richmond Climax carried an article about the company, which noted they were in the process of completing a new $53,000 factory at the penitentiary:

... The lessees will place new machinery in this building for the manufacture of chairs exclusively... For some time they have manufactured wagons and carts, but they intend to abandon that branch entirely, so they may have more room to enable them to increase the manufacture of ladies' shoes, the demand for which is increasing daily... The manufacture of brooms will be continued, and the capacity of the factory will be doubled...

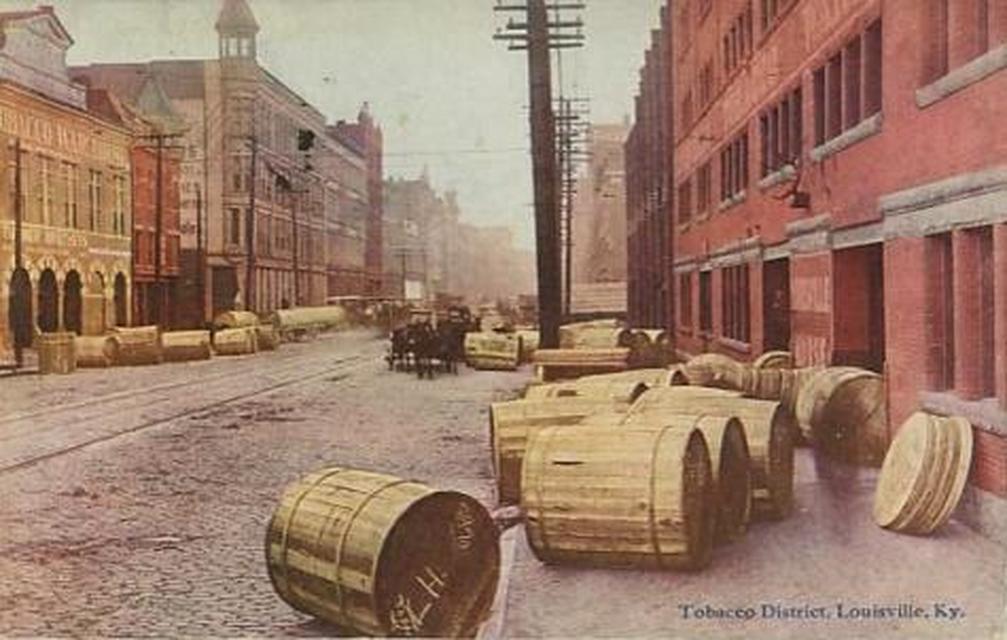

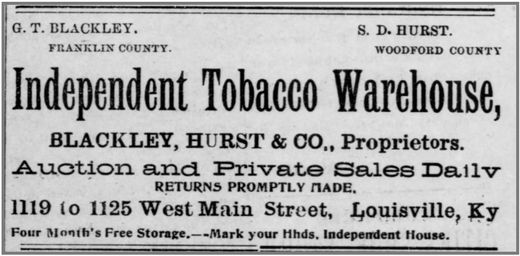

The Kentucky Chair Company was spun off by Mason and Foard, and G.T. became a partner in the venture. In 1896 the company ran into legal problems with the Commonwealth of Kentucky over non-payment of bills, likely forcing G.T. to find another source of income. By the time the Blackleys moved to Pewee Valley, G.T. was in the tobacco business. He and partner S.D. Hurst were advertising their "Independent Tobacco Warehouses" on Main Street in the heart of Louisville's tobacco district in newspapers throughout central Kentucky.

G.T., his wife, Ophelia "Nina" Winston, and their four children – Nanny W., Margaret "French," Charles Mason and James "Norman" – appear to have moved to Pewee Valley in 1898, based on the 1899-1900 Announcement catalog for the Kentucky College for Young Ladies. Their three oldest children were listed as pupils during the school's 1898-99 session.

Once the Blackleys arrived, they immersed themselves in local affairs. “They wanted to get into Pewee Valley society,” Murphy recalled. G.T. served on the Town Council for many years. And ironically enough – at least from former owner William Gallagher’s perspective! -- Ophelia was very active in the United Daughters of the Confederacy Kentucky Confederate Home Chapter No. 792.

Ophelia had two claims to UDC membership: her father and her uncle. She was born in Virginia in 1863 and her father, William Derracott Winston, enlisted in Company C, Virginia 15th Infantry Regiment on July 16, 1861. Although U.S. military records show he died at Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862 during the second day of fighting at Antietam, further research by her grandson, Winston Blackley, proved that, though he was wounded, he survived. "He made it home to his farm at Rose Hill in Montpelier, Va., and his wife got him back on his feet," he said in a February 2018 interview.

Ophelia had two claims to UDC membership: her father and her uncle. She was born in Virginia in 1863 and her father, William Derracott Winston, enlisted in Company C, Virginia 15th Infantry Regiment on July 16, 1861. Although U.S. military records show he died at Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862 during the second day of fighting at Antietam, further research by her grandson, Winston Blackley, proved that, though he was wounded, he survived. "He made it home to his farm at Rose Hill in Montpelier, Va., and his wife got him back on his feet," he said in a February 2018 interview.

Rose Hill in Virginia: The Vaughan Family Home During the First Half of the 19th Century

Rose Hill, Ophelia's family home in Virginia, where her father was shot and killed by marauding Yankees as he stood in the front door. Courtesy of Winston Blackley.

Ophelia was conceived while he was convalescing at Rose Hill. Unfortunately, he didn't live to see his daughter's birth. He was shot and killed when a band of marauding Yankees showed up at the farm, about 30 miles north of Richmond. "He confronted them and they shot him in his front door," says Blackley. "There's still a bullet hole in the floor."

Ophelia's maternal uncle, John T. Vaughn, also fought for the Rebel cause, but survived the war and marauding Yankees, as well. Like his brother-in-law William Delacroix Winston, he enlisted in Virginia, but served in Capt. A.J. Jones’ Company Virginia Heavy Artillery, also known as Pamunkey Artillery.

Ophelia served as President of Chapter 792 the year it was organized. Other members of the chapter included many of the home's directors' wives as well as several Pewee Valley women, including Mrs. W.N. Jurey, Mrs. Clem B. Johnson, Mrs. C.D. Moody, Mrs. Josephine Nock, Mrs. Annie Nock and Ophelia's daughters, Nannie and French. Florence Barlow, who worked at the home as secretary/bookkeeper and later published the home's newsletter, the Confederate Home Messenger, was also a member. The chapter’s monthly meetings were held in the home's parlor.

Ophelia's maternal uncle, John T. Vaughn, also fought for the Rebel cause, but survived the war and marauding Yankees, as well. Like his brother-in-law William Delacroix Winston, he enlisted in Virginia, but served in Capt. A.J. Jones’ Company Virginia Heavy Artillery, also known as Pamunkey Artillery.

Ophelia served as President of Chapter 792 the year it was organized. Other members of the chapter included many of the home's directors' wives as well as several Pewee Valley women, including Mrs. W.N. Jurey, Mrs. Clem B. Johnson, Mrs. C.D. Moody, Mrs. Josephine Nock, Mrs. Annie Nock and Ophelia's daughters, Nannie and French. Florence Barlow, who worked at the home as secretary/bookkeeper and later published the home's newsletter, the Confederate Home Messenger, was also a member. The chapter’s monthly meetings were held in the home's parlor.

|

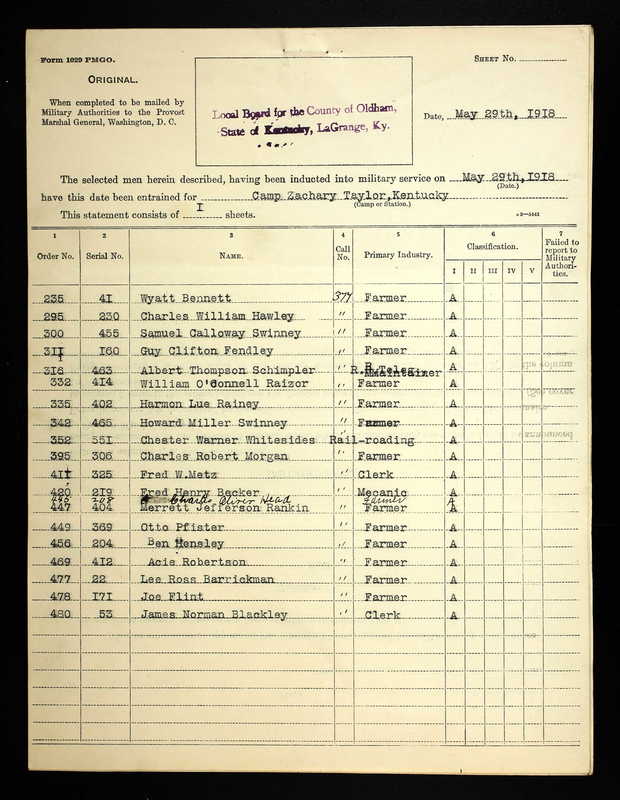

List of Pewee Valley Men Inducted into the Army on May 29, 1918

|

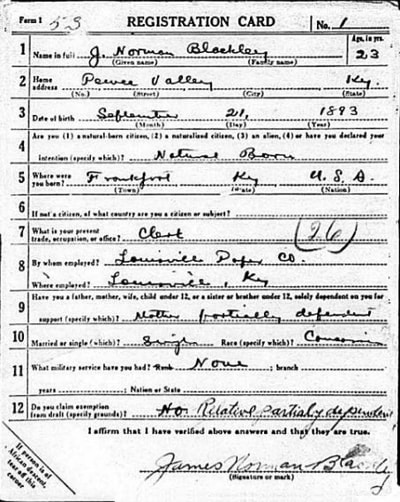

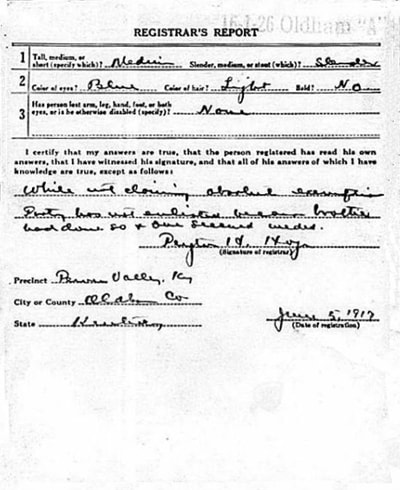

G.T. doesn't appear to have been much of a success as a businessman. By 1910, he was out of the tobacco warehouse business entirely, and the census listed his occupation as "Home Farmer." His older son, Charles Mason, was helping him on the farm. The U.S.'s entrance into World War I on April 6, 1917, brought change to America, as President Woodrow Wilson enacted a national draft. More than 2 million men were called to serve on the battlefields of Western Europe, where a quarter of them died. Pewee Valley didn't escape Uncle Sam's call to arms. Among the 20 Peweeans who registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, and were inducted into the army at Camp Zachary Taylor on May 29, 1918 was James Norman Blackley, Ophelia's and G.T.'s youngest child. James Norman may have qualified for an exemption, but elected not to take it. His registration papers, signed by Peyton H. Hoge, pastor of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church, noted that he was partially responsible for the support of his mother and that his brother had already registered. |

James Norman Blackley Draft Registration

By the 1920 Census, G.T. was 71, Ophelia was 57, their four children were grown, and all of them were living at home and employed at various occupations. The 1920 Census shows that Nanny Winston (1883–1968) was working as a clerk at the Internal Revenue Service; Margaret French Blackley (1885-1976) was working as a teacher; Charles Mason Blackley (1889–1937) was working as a hardware salesman; and James Norman Blackley (1893–1945) had returned from his WWI service to his job at the Louisville Paper Company, owned by former Peweean Thomas Floyd Smith, III. G.T.'s occupation was listed as farmer.

On March 25, 1920, the Kentucky Confederate Home went up in flames. The next day, the Courier-Journal reported:

…Sparks carried in the wind almost a quarter of a mile, set fire to the home of Mrs. G.T. Blackley. Scores of persons assisted in saving the furniture. The residence was one of the show places of Oldham County. Within a short time, the trees over several acres of ground caught fire…

This was the second time a serious fire occurred at Undulata. Four years earlier, the rear of the house had been badly damaged. The April 14, 1916 Courier-Journal reported:

BEAUTIFUL PEWEE VALLEY

HOME DAMAGED BY FIRE

Fire originating in the roof of the residence of G.T. Blackley yesterday morning, threatened for a time to destroy one of the oldest and most beautiful homes in Pewee Valley.

The blaze was discovered by Mrs. Blackley from the yard. She immediately telephoned an alarm around the neighborhood and aid was soon arriving at the scene. Before the blaze was finally extinguished two rooms in the rear of the house were gutted. The damage was estimated at $1,000, covered by insurance.

Very little survived of the original Villa Ridge Hotel but smoking ruins the fire the night the Confederate Home burned down. Undulata/Fern Rock Cottage suffered the same fate. Today, only the stone pillars and iron gate near the intersection of Peace and Muirs lanes remain. According to Winston Blackley, his father, James Norman Blackley, didn't talk much about the fire, but he did say he lost a lot of mementos from his front-line infantry service in the blaze.

…Sparks carried in the wind almost a quarter of a mile, set fire to the home of Mrs. G.T. Blackley. Scores of persons assisted in saving the furniture. The residence was one of the show places of Oldham County. Within a short time, the trees over several acres of ground caught fire…

This was the second time a serious fire occurred at Undulata. Four years earlier, the rear of the house had been badly damaged. The April 14, 1916 Courier-Journal reported:

BEAUTIFUL PEWEE VALLEY

HOME DAMAGED BY FIRE

Fire originating in the roof of the residence of G.T. Blackley yesterday morning, threatened for a time to destroy one of the oldest and most beautiful homes in Pewee Valley.

The blaze was discovered by Mrs. Blackley from the yard. She immediately telephoned an alarm around the neighborhood and aid was soon arriving at the scene. Before the blaze was finally extinguished two rooms in the rear of the house were gutted. The damage was estimated at $1,000, covered by insurance.

Very little survived of the original Villa Ridge Hotel but smoking ruins the fire the night the Confederate Home burned down. Undulata/Fern Rock Cottage suffered the same fate. Today, only the stone pillars and iron gate near the intersection of Peace and Muirs lanes remain. According to Winston Blackley, his father, James Norman Blackley, didn't talk much about the fire, but he did say he lost a lot of mementos from his front-line infantry service in the blaze.

Central Place Subdivision

From "A Place Called Pewee Valley" published in 1970 by the Pewee Valley Centennial Commission From "A Place Called Pewee Valley" published in 1970 by the Pewee Valley Centennial Commission

|

Three years later, the Blackleys ended up purchasing another Pewee Valley home – the Truman-Miller-Richard House. "My father never considered that house his home," Winston noted.

The Undulata property was eventually purchased and another home was built on it. That house, shown at left, did not survive the march of progress. It was torn down in 1992 to make way for Central Place Subdivision. |

Related Links