The Locust: In the Beginning and the Rhorer Years

In the Beginning: A Revolutionary War Land Grant

The Avenue of Trees post card by Kate Matthews. Courtesy of the late B. Utley Murphy.

The Avenue of Trees post card by Kate Matthews. Courtesy of the late B. Utley Murphy.

Author Annie Fellows Johnston's Little Colonel stories brought The Locust world-wide fame, when she used it as the fictional home of cantankerous Old Colonel Lloyd.

In real life, George Washington Weissinger -- Annie's inspiration for the Old Colonel -- never owned the house, although he did board there for awhile during the 1890s. In an interview that appeared in the June 2, 1907 issue of The San Antonio Light, Annie showed the reporter a photo of The Locust and noted, "...Here on the gallery at the end of the long avenue of locusts, the Old Colonel would sit and watch the passors by (sic) through his spy glass."

While The Locust played a major role as the setting for many events in the Little Colonel novels, it's important to Pewee Valley's history for other reasons, as well.

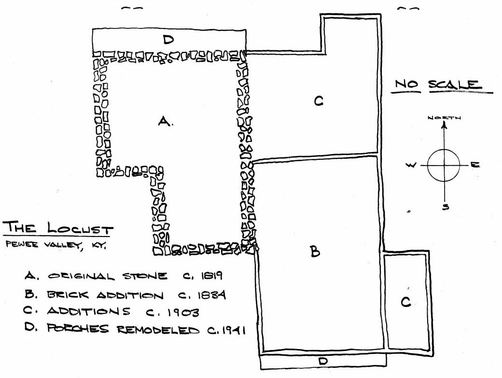

The Locust is one of Pewee Valley's oldest surviving homes, with portions dating to 1819 or before. According to the National Register of Historic Places nomination submitted in 1975, it offers "...an interesting example of the evolution of architecture in Kentucky. The house spans several different periods, from the early settlement through the Victorian era to the 20th century..."

In real life, George Washington Weissinger -- Annie's inspiration for the Old Colonel -- never owned the house, although he did board there for awhile during the 1890s. In an interview that appeared in the June 2, 1907 issue of The San Antonio Light, Annie showed the reporter a photo of The Locust and noted, "...Here on the gallery at the end of the long avenue of locusts, the Old Colonel would sit and watch the passors by (sic) through his spy glass."

While The Locust played a major role as the setting for many events in the Little Colonel novels, it's important to Pewee Valley's history for other reasons, as well.

The Locust is one of Pewee Valley's oldest surviving homes, with portions dating to 1819 or before. According to the National Register of Historic Places nomination submitted in 1975, it offers "...an interesting example of the evolution of architecture in Kentucky. The house spans several different periods, from the early settlement through the Victorian era to the 20th century..."

Schematic showing the various additions to The Locust over the years. From the National Register of Historic Places nomination, 1975.

Schematic showing the various additions to The Locust over the years. From the National Register of Historic Places nomination, 1975.

The nomination goes on to explain:

The property on which the Locust is built was originally part of a 4,000-acre land grant which was granted to Samuel Beall in 1784 by Patrick Henry. Beall sold several hundred acres of the land to George Nicholas ( ? - 1799) the prominent lawyer and first Attorney General of Kentucky . Nicholas never paid the purchase price and contracted 200 acres to Robert Wooden, who took possession of the land during Nicholas' lifetime and made valuable improvements on it. The date of the deed is 1819. It is indicated that this is probably when the stone portion of the house was constructed, although there is a tradition that this structure and the stone springhouse nearby date from considerably earlier. The house changed owners many times after 1834 when Robert Wooden sold it to John Howell. In 1850 the estate, which included a number of slaves, was auctioned. The auction was the result of a suit filed by the owner's wife, Ann Gough, against her husband and his heirs. It took place in compliance with an order of the Oldham County Court. After the auction the house changed hands several times, until 1857 when Jonas H. Rhorer purchased the property.

The property on which the Locust is built was originally part of a 4,000-acre land grant which was granted to Samuel Beall in 1784 by Patrick Henry. Beall sold several hundred acres of the land to George Nicholas ( ? - 1799) the prominent lawyer and first Attorney General of Kentucky . Nicholas never paid the purchase price and contracted 200 acres to Robert Wooden, who took possession of the land during Nicholas' lifetime and made valuable improvements on it. The date of the deed is 1819. It is indicated that this is probably when the stone portion of the house was constructed, although there is a tradition that this structure and the stone springhouse nearby date from considerably earlier. The house changed owners many times after 1834 when Robert Wooden sold it to John Howell. In 1850 the estate, which included a number of slaves, was auctioned. The auction was the result of a suit filed by the owner's wife, Ann Gough, against her husband and his heirs. It took place in compliance with an order of the Oldham County Court. After the auction the house changed hands several times, until 1857 when Jonas H. Rhorer purchased the property.

The Rhorer Years

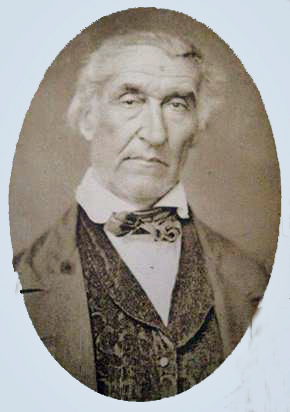

According to his great-great grandson, Richard A. Barclay, Jonas Huber Rhorer (1814-1896) and his wife, Julia Ann Comly Rhorer (1822-1898), moved to The Locust in 1857 with their two children:

- Louisa Rhorer (1841–1918), who later married Thomas P. Barclay and lived across the tracks from her parents at Tanglewood

- Melvin Rhorer (1843–1910), who attended the University of Louisville and became a physician.

Their third child, son Richard Comly Rhorer, had died in infancy in 1846.

At the time he purchased The Locust from Hugh Wilkins, there were 120 acres associated with property. There had been 160 when Wilkins bought the estate in 1848 at a public sale in LaGrange -- for $5 per acre, no less -- but he sold 40 acres within a few months to James A. Miller for $800 -- a tidy profit of $15 an acre.

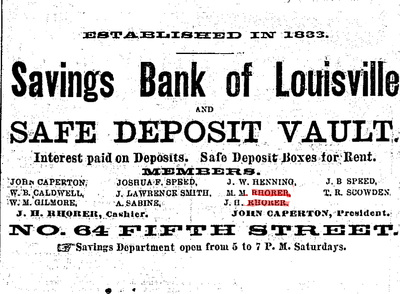

Raised in Nicholasville, Ky., Rhorer was 21 years old when he arrived in Louisville in 1835. By the next year he had joined the recently-formed Louisville Savings Institution as both an employee and officer. Rhorer remained with the bank his entire career, serving at various times as cashier, president or both, and continued his association with the financial institution after it was rechartered as the Savings Bank of Louisville in 1866.

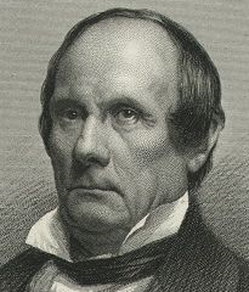

James Guthrie ((December 5, 1792 – March 13, 1869) was an early stockholder in the Louisville Savings Institution, represented Kentucky in the U.S. Senate, and served as the country's 21st Secretary of the Treasury.

James Guthrie ((December 5, 1792 – March 13, 1869) was an early stockholder in the Louisville Savings Institution, represented Kentucky in the U.S. Senate, and served as the country's 21st Secretary of the Treasury.

James Guthrie, one of the bank's early stockholders, was also President of the Louisville and Portland Canal Company. The bank opened in 1833 -- the year the first steamboat came through the locks. It became the depository for the canal's toll income and provided office space for its operations, as well. In 1847, Rhorer was appointed secretary/ treasurer of the Louisville and Portland Canal, a position he held until the federal government purchased it in May, 1874. In addition, he served as an agent of the Advisory Board of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Lexington Railroad.

Rhorer also had an interest in real estate, and within a decade of moving to Pewee Valley, was speculating in local properties. In 1867, he, along with Harry Mith (probably Henry Smith) and J.F. Gamble, chartered a building association to "... promote the settling up of Pewee Valley, by buying lots and building houses thereon for sale to such persons as may wish to settle in the neighborhood." According to historian Carolyn Brooks, Rhorer’s name was attached to seven Pewee Valley houses between the 1860s and 1870s, and he, along with investor Charles Cotton, was also partial owner of other properties through the building association.

To promote Pewee Valley's development, Rhorer supported several major community endeavors, including construction of the train depot in 1867, the founding of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church in 1868, and the establishment of the Kentucky College for Young Ladies on Ashwood Avenue in 1873.

He was a well-liked and well-respected man among both his business associates and fellow Peweeans. Later, he would be described by the Courier-Journal as an "...old, white-haired gentleman, with...kind and benevolent features..." who was looked upon by those who knew him as "...the soul of honesty and integrity, and a business man whose accuracy and attention to exact detail were, if anything, rather too severe. " The New York Times would call his face, "...the picture of high-bred benevolence and honesty."

Rhorer also had an interest in real estate, and within a decade of moving to Pewee Valley, was speculating in local properties. In 1867, he, along with Harry Mith (probably Henry Smith) and J.F. Gamble, chartered a building association to "... promote the settling up of Pewee Valley, by buying lots and building houses thereon for sale to such persons as may wish to settle in the neighborhood." According to historian Carolyn Brooks, Rhorer’s name was attached to seven Pewee Valley houses between the 1860s and 1870s, and he, along with investor Charles Cotton, was also partial owner of other properties through the building association.

To promote Pewee Valley's development, Rhorer supported several major community endeavors, including construction of the train depot in 1867, the founding of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church in 1868, and the establishment of the Kentucky College for Young Ladies on Ashwood Avenue in 1873.

He was a well-liked and well-respected man among both his business associates and fellow Peweeans. Later, he would be described by the Courier-Journal as an "...old, white-haired gentleman, with...kind and benevolent features..." who was looked upon by those who knew him as "...the soul of honesty and integrity, and a business man whose accuracy and attention to exact detail were, if anything, rather too severe. " The New York Times would call his face, "...the picture of high-bred benevolence and honesty."

Advertisements for the Savings Bank of Louisville

Imagine his friends' and neighbors' shock and dismay the morning of January 15, 1880 when they opened their morning Courier-Journals and learned that Rhorer had embezzled $67,500 from the Savings Bank of Louisville. It was the talk of the town. All Louisville was abuzz with the scandal, and the story even made the New York Times. The next day's Courier-Journal noted the somber scene on the Short-line commuter train to Louisville the morning the story broke:

...For seventeen years, Mr. Rhorer has been a fixture upon that early train, never failing to be on hand, always having a pleasant greeting for every one. He was almost regarded by his fellow passengers in the light of a father. Yesterday morning he was absent from the cars, and as each of his intimate friends would open his daily paper, the unwelcome and stunning explanation of his absence greeted him. No comments were made upon the affair, each one being too much shocked to discuss the matter. One of the passengers said yesterday, that he felt himself and he believed every one on the train felt the same way, that if he were alone, nothing could restrain him from venting his sorrow in a flood of tears.

As the days wore on, and an outside accountant was called in to examine the bank's books, the amount of Rhorer's defalcation grew. Eventually, it reached a staggering $118,000, the equivalent of $2.7 million today.

Rhorer readily admitted his guilt. His crime was uncovered, because he left a note on the counter near his books stating:

I am a defaulter and a large defaulter probably to the extent of the entire capital stock of this bank. I have gone to jail and shall give myself up.

He was found sitting on the jailhouse steps shortly after his note was discovered. Brought back and quizzed by the other directors, he confessed he'd been embezzling for years and covering his trail with false entries and balances. A lawsuit later brought against the bank directors for negligence provides the sordid details of how Rhorer cooked the bank's books and took down the bank, whose directors included Joshua F. Speed, close friend of Abraham Lincoln:

…The frauds perpetrated by the cashier in abstracting the money of the bank were committed in various ways: First. When deposits in certain instances were made he would credit them on the individual ledger, but make no charge on the blotter. In one instance, the Louisville Steel-Works is credited on the individual ledger with $5,000, and this sum not credited to the concern or charged to cash on the blotter. Again, the same party is credited by several items, amounting to $2,719, in the same way. Second. The blotter shows a deposit on January 25th of $3,898.50, and on that day Rohrer & Cotton are credited with that amount on the individual ledger. On the same day the Metropolitan National Bank of New York is credited on the blotter with $6,101.50. These two items amount to $10,000, and the bank on the general ledger is credited by $10,000. It appears that the Metropolitan Bank was entitled to a credit of $10,000, when Rhorer only placed to its credit $6,101.50, and gave credit to Rhorer & Cotton for $3,898.50, when no such deposit had been made; but by crediting the bank's account in the ledger with the true amount, $10,000, the accounts appeared correct, and enabled the cashier to appropriate $3,898.50 to his own use. Another instance is where Rhorer is credited on the blotter with $350, and this sum is posted to his account in the individual ledger as $2,350. Again, he would charge a depositor on the blotter with a certain sum, as if paid on the depositor's check. This sum would be posted to his account on the individual ledger, and when balancing the account the item would be omitted from the addition. This character of fraudulent entries …was practiced from the year 1871 until the close of the bank, in January, 1880...

From The Southwestern Reporter, Volume 8, Containing All the Current Decisions of the Supreme Courts of Missouri, Arkansas, and Tennessee, Court of Appeals of Kentucky, and Supreme Court and Court of Appeals (Criminal Cases) of Texas May 28-July 30, 1888” (West Publishing Co., St. Paul; 1888.)

Where did the money go? Most went into real estate speculation in Pewee Valley and California during the boom after the Civil War. But those investments lost their value when the Panic of 1873 hit, bringing with it stock market crashes, bank failures, deflation in the value of real estate and other property, partially-completed railroads, idle factories, the demise of many small businesses, and high unemployment. It was a period much like the real estate bubble crash in 2008 and lasted eight long years.

According to the National Register nomination for The Locust, the first sign that Rhorer was in financial trouble occurred in 1873, when he mortgaged his home to Sidney J. Hobbs in Anchorage. He mortgaged it again in 1876 to Joshua F. Speed, who was an officer and major stockholder in the bank.

The second warning of Rhorer's deepening financial woes was the 1878 bankruptcy of his neighbor and fellow building association investor Charles B. Cotton. Cotton lost everything in the bankruptcy -- his beautiful mansion, which once stood on Confederate Hill overlooking downtown and the railroad; his personal possessions; and a large parcel of land on the west side of Central Avenue extending from Peace Farm to Rollington Road.

By December 1879, when asked to prepare the annual year-end statement for the commercial side of the bank, Rhorer could no longer hide his defalcations and confessed to his crime on January 9, 1880.

...For seventeen years, Mr. Rhorer has been a fixture upon that early train, never failing to be on hand, always having a pleasant greeting for every one. He was almost regarded by his fellow passengers in the light of a father. Yesterday morning he was absent from the cars, and as each of his intimate friends would open his daily paper, the unwelcome and stunning explanation of his absence greeted him. No comments were made upon the affair, each one being too much shocked to discuss the matter. One of the passengers said yesterday, that he felt himself and he believed every one on the train felt the same way, that if he were alone, nothing could restrain him from venting his sorrow in a flood of tears.

As the days wore on, and an outside accountant was called in to examine the bank's books, the amount of Rhorer's defalcation grew. Eventually, it reached a staggering $118,000, the equivalent of $2.7 million today.

Rhorer readily admitted his guilt. His crime was uncovered, because he left a note on the counter near his books stating:

I am a defaulter and a large defaulter probably to the extent of the entire capital stock of this bank. I have gone to jail and shall give myself up.

He was found sitting on the jailhouse steps shortly after his note was discovered. Brought back and quizzed by the other directors, he confessed he'd been embezzling for years and covering his trail with false entries and balances. A lawsuit later brought against the bank directors for negligence provides the sordid details of how Rhorer cooked the bank's books and took down the bank, whose directors included Joshua F. Speed, close friend of Abraham Lincoln:

…The frauds perpetrated by the cashier in abstracting the money of the bank were committed in various ways: First. When deposits in certain instances were made he would credit them on the individual ledger, but make no charge on the blotter. In one instance, the Louisville Steel-Works is credited on the individual ledger with $5,000, and this sum not credited to the concern or charged to cash on the blotter. Again, the same party is credited by several items, amounting to $2,719, in the same way. Second. The blotter shows a deposit on January 25th of $3,898.50, and on that day Rohrer & Cotton are credited with that amount on the individual ledger. On the same day the Metropolitan National Bank of New York is credited on the blotter with $6,101.50. These two items amount to $10,000, and the bank on the general ledger is credited by $10,000. It appears that the Metropolitan Bank was entitled to a credit of $10,000, when Rhorer only placed to its credit $6,101.50, and gave credit to Rhorer & Cotton for $3,898.50, when no such deposit had been made; but by crediting the bank's account in the ledger with the true amount, $10,000, the accounts appeared correct, and enabled the cashier to appropriate $3,898.50 to his own use. Another instance is where Rhorer is credited on the blotter with $350, and this sum is posted to his account in the individual ledger as $2,350. Again, he would charge a depositor on the blotter with a certain sum, as if paid on the depositor's check. This sum would be posted to his account on the individual ledger, and when balancing the account the item would be omitted from the addition. This character of fraudulent entries …was practiced from the year 1871 until the close of the bank, in January, 1880...

From The Southwestern Reporter, Volume 8, Containing All the Current Decisions of the Supreme Courts of Missouri, Arkansas, and Tennessee, Court of Appeals of Kentucky, and Supreme Court and Court of Appeals (Criminal Cases) of Texas May 28-July 30, 1888” (West Publishing Co., St. Paul; 1888.)

Where did the money go? Most went into real estate speculation in Pewee Valley and California during the boom after the Civil War. But those investments lost their value when the Panic of 1873 hit, bringing with it stock market crashes, bank failures, deflation in the value of real estate and other property, partially-completed railroads, idle factories, the demise of many small businesses, and high unemployment. It was a period much like the real estate bubble crash in 2008 and lasted eight long years.

According to the National Register nomination for The Locust, the first sign that Rhorer was in financial trouble occurred in 1873, when he mortgaged his home to Sidney J. Hobbs in Anchorage. He mortgaged it again in 1876 to Joshua F. Speed, who was an officer and major stockholder in the bank.

The second warning of Rhorer's deepening financial woes was the 1878 bankruptcy of his neighbor and fellow building association investor Charles B. Cotton. Cotton lost everything in the bankruptcy -- his beautiful mansion, which once stood on Confederate Hill overlooking downtown and the railroad; his personal possessions; and a large parcel of land on the west side of Central Avenue extending from Peace Farm to Rollington Road.

By December 1879, when asked to prepare the annual year-end statement for the commercial side of the bank, Rhorer could no longer hide his defalcations and confessed to his crime on January 9, 1880.

A month later, Rhorer was indicted for embezzlement and on April 7, was sentenced to a year in the State Penitentiary:

STATE OF KENTUCKY,

JEFFERSON COUNTY.

Pleas before the Honorable W. L. Jackson, Judge of the Jefferson

Circuit Court, held at the court-house thereof, in the city of Louisville,

on the — day of ——, I880.

Be it remembered that heretofore, to-wit, on the 10th day of February, I880, the foreman of the grand jury, in the presence of the grand jury, returned an indictment a true bill against J. H. Rhorer for embezzlement. Said indictment is in words and figures as follows, to-wit:

The Commonwealth of Kentucky against J.H. Rhorer—Jefferson Circuit Court, February Term, 1880.

The grand jurors of the county of Jefferson, in the name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, accuse J. H. Rhorer of the crime of embezzlement, committed in manner and form as follows, to~wit:

The said J. H. Rhorer, in the said county of Jefferson, on the —day of December, A. D. I879, and before the finding of this indictment, he then being an officer, servant, and agent, to-wit: Cashier of the Louisville Savings Bank, a corporation duly incorporated and organized by and under the laws of the State of Kentucky, and having, by virtue of said office of cashier, received and had placed in his care the sum of $100,000 in lawful money and currency of the United States, did, feloniously and fraudulently embezzle and convert to his own use and benefit the sum aforesaid; which said sum was the property of said Louisville Savings Bank, and which sum had been placed in his hands and under his care as such officer, servant, and agent, to-wit: Cashier of said Louisville Savings Bank, contrary to the form of statute in such cases made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Witnesses:

J. W. Henry J. F. Speed, Jr.,

J. F. Speed T. P. Smith,

John Caperton T. C. Kinegarsholt (Editor's note: this is probably T.C. Vennigerholtz, who lived in Pewee Valley and was

D. T. Bligh, hired as the forensic accountant to determine the bank's losses)

That at a court held for the aforesaid heretofore, on the 10th day of February, 1880, the following order was entered, viz:

The defendant is this day led to the bar of this court, and the court, with the consent of the defendant, dispenses with the arraignment, and the defendant pleads that he is not guilty of the offense charged in the indictment.

And at a court continued and held for the county aforesaid, heretofore, on the 7th day of April, I880, the following order was entered: The defendant, in pursuance of his recognizance, this day appears at the bar of this court, and having heretofore pleaded not guilty of offense charged in indictment, now offers and files the following plea in writing:

The defendant, Jonas H. Rhorer, for plea to the indictment herein, says, that although he never intended to misappropriate the funds of the LouisvilleSavings Bank, but always intended to replace them, and would have done so but for unexpected financial misfortune; yet, as he is technically guilty as to a part of the sum which he is charged to have embezzled, he pleads guilty to said charge, and only asks for mercy of the jury in their verdict. (Signed) J. H. RHORER.

To which the attorney for the Commonwealth objected; said objection being heard, was submitted, and the court being advised, ordered said objection be sustained, and refuses to allow said plea, to which the defendant excepts. Thereupon the defendant, with the permission of the court, withdraws his said former plea of “not guilty,’ and now in open court pleads that he is guilty of the offense charged in the indictment. To fix the punishment of the defendant, comes the jury, to-wit:

B. H. Bland H. L. Gaar,

F. A. Crump, H. W. Gray,

M. Dally, M. Lapaille,

D. H. Wigginton, Geo. B. Johnson,

E. D. Beatty, N. Yeager,

R. A. Thomas, Geo. C. Avery.

Who, being duly elected and sworn according to law, after retiring to consult, returned the following verdict, viz:

We, the jury, find the defendant guilty as charged in the within indictment, and fix punishment at confinement in the State Penitentiary for the period of one year, and recommend him to Executive clemency. .-' HENRY W. GRAY, Foreman.

It is therefore ordered that the defendant be remanded to the jail of Jefferson county.

STATE OF KENTUCKY,

JEFFERSON COUNTY.

I, John S. Cain, Clerk of the Jefferson Circuit Court, do certify that the foregoing 4 pages, this one included, contain a full, true, and complete transcript of the record and proceedings had in said court in the case therein mentioned, except the bond of defendant and order of continuance.

Witness my hand, clerk aforesaid, this 7th day of April, A. D. I880.

JOHN S. CAIN, Clerk.

STATE OF KENTUCKY,

JEFFERSON COUNTY.

Pleas before the Honorable W. L. Jackson, Judge of the Jefferson

Circuit Court, held at the court-house thereof, in the city of Louisville,

on the — day of ——, I880.

Be it remembered that heretofore, to-wit, on the 10th day of February, I880, the foreman of the grand jury, in the presence of the grand jury, returned an indictment a true bill against J. H. Rhorer for embezzlement. Said indictment is in words and figures as follows, to-wit:

The Commonwealth of Kentucky against J.H. Rhorer—Jefferson Circuit Court, February Term, 1880.

The grand jurors of the county of Jefferson, in the name and by the authority of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, accuse J. H. Rhorer of the crime of embezzlement, committed in manner and form as follows, to~wit:

The said J. H. Rhorer, in the said county of Jefferson, on the —day of December, A. D. I879, and before the finding of this indictment, he then being an officer, servant, and agent, to-wit: Cashier of the Louisville Savings Bank, a corporation duly incorporated and organized by and under the laws of the State of Kentucky, and having, by virtue of said office of cashier, received and had placed in his care the sum of $100,000 in lawful money and currency of the United States, did, feloniously and fraudulently embezzle and convert to his own use and benefit the sum aforesaid; which said sum was the property of said Louisville Savings Bank, and which sum had been placed in his hands and under his care as such officer, servant, and agent, to-wit: Cashier of said Louisville Savings Bank, contrary to the form of statute in such cases made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Witnesses:

J. W. Henry J. F. Speed, Jr.,

J. F. Speed T. P. Smith,

John Caperton T. C. Kinegarsholt (Editor's note: this is probably T.C. Vennigerholtz, who lived in Pewee Valley and was

D. T. Bligh, hired as the forensic accountant to determine the bank's losses)

That at a court held for the aforesaid heretofore, on the 10th day of February, 1880, the following order was entered, viz:

The defendant is this day led to the bar of this court, and the court, with the consent of the defendant, dispenses with the arraignment, and the defendant pleads that he is not guilty of the offense charged in the indictment.

And at a court continued and held for the county aforesaid, heretofore, on the 7th day of April, I880, the following order was entered: The defendant, in pursuance of his recognizance, this day appears at the bar of this court, and having heretofore pleaded not guilty of offense charged in indictment, now offers and files the following plea in writing:

The defendant, Jonas H. Rhorer, for plea to the indictment herein, says, that although he never intended to misappropriate the funds of the LouisvilleSavings Bank, but always intended to replace them, and would have done so but for unexpected financial misfortune; yet, as he is technically guilty as to a part of the sum which he is charged to have embezzled, he pleads guilty to said charge, and only asks for mercy of the jury in their verdict. (Signed) J. H. RHORER.

To which the attorney for the Commonwealth objected; said objection being heard, was submitted, and the court being advised, ordered said objection be sustained, and refuses to allow said plea, to which the defendant excepts. Thereupon the defendant, with the permission of the court, withdraws his said former plea of “not guilty,’ and now in open court pleads that he is guilty of the offense charged in the indictment. To fix the punishment of the defendant, comes the jury, to-wit:

B. H. Bland H. L. Gaar,

F. A. Crump, H. W. Gray,

M. Dally, M. Lapaille,

D. H. Wigginton, Geo. B. Johnson,

E. D. Beatty, N. Yeager,

R. A. Thomas, Geo. C. Avery.

Who, being duly elected and sworn according to law, after retiring to consult, returned the following verdict, viz:

We, the jury, find the defendant guilty as charged in the within indictment, and fix punishment at confinement in the State Penitentiary for the period of one year, and recommend him to Executive clemency. .-' HENRY W. GRAY, Foreman.

It is therefore ordered that the defendant be remanded to the jail of Jefferson county.

STATE OF KENTUCKY,

JEFFERSON COUNTY.

I, John S. Cain, Clerk of the Jefferson Circuit Court, do certify that the foregoing 4 pages, this one included, contain a full, true, and complete transcript of the record and proceedings had in said court in the case therein mentioned, except the bond of defendant and order of continuance.

Witness my hand, clerk aforesaid, this 7th day of April, A. D. I880.

JOHN S. CAIN, Clerk.

Despite the magnitude of his crime and subsequent bankruptcy of the financial institution, it wasn't surprising the jury recommended clemency. During the weeks between Rhorer's indictment and sentencing, Kentucky Governor Luke P. Blackburn was bombarded with entreaties to pardon Rhorer. They came from residents, businessmen and politicians in Bowling Green, Lebanon, Russellville, Louisville, Richmond, Columbia, Lancaster, Glasgow, Henderson, Harrisburg, Danville, LaGrange and Pewee Valley. Among the scores of people asking for Executive clemency were the directors of the Savings Bank of Louisville themselves!

The petitioners cited his advanced age; an otherwise spotless life; the impact of imprisonment on his wife, children, grandchildren and other family members; his lack of criminal intent coupled with deep repentance for his crime; his popularity; his modest demeanor and lack of ostentation; the Panic of 1873; and the fact that his elderly wife also gave up her own inheritance to help pay the bank's customers back. The petition below, signed by 51 of Rhorer's neighbors in Pewee Valley -- some 80 percent of the town's adult populaton at that time -- was typical of the many the Governor received:

To his Excellency, L. P. BLACKBURN, Governor of Kentucky:

The undersigned, your petitioners, respectfully show unto your Excellency that Jonas H. Rhorer has been indicted in the Jefferson Circuit Court for the crime of embezzlement. Your petitioners are residents of Pewee Valley and its vicinity, and have been, and still are, the neighbors and friends of the accused. Having known him long and well, we say to your Excellency that his character for integrity has always been of the highest and purest, and we feel sure that he never intended to commit the crime of which he is charged. That he has done wrong, may be technically guilty, we admit; but we are satisfied that the money which may have been misappropriated was never applied to his own use, and that he never intended to commit a crime, but, on the other hand, fully intended to restore it all. The great depreciation in the value of property, the large losses which he sustained by endorsements, and the unexpected failure of business enterprises, rendered him unable to carry out his intentions. He is now old, and neither he nor his aged and excellent wife can survive the punishment prescribed by law. His children and grandchildren have already suffered deeply, and these and the good old wife, mother, and grandmother, should, if possible, be spared any further shame and suffering. Truly this is a proper case for Executive clemency, and we but echo the general public sentiment when we earnestly ask your Excellency to grant him a pardon.

Mrs. John Watt Moore Lillian Myer,

Mrs. Blanche Smith Mrs. L. R. Myer,

Mrs. C. J. F. Allen, Lizzie P. Armstrong,

Mrs. Craig, Alice B. Armstrong,

Alice Craig, Nellie Vanhorn,

Fannie Craig, Nellie View,

Mrs. G. Foley, P. P. Muse,

Ellen Foley, M. Awkard,

Mary Foley, H. M. Wolfork,

Mrs. A. W. Cayer C. I. Woodfork,

Sarah A. Gordon M. S. Buckner,

Mary J. Hudson, C. Bradley,

Mattie Rabbitt, Samuel L. Knox

Mrs. T. Wind, Earnest Bowley,

Geo. C. Miller, D. A. Wilson,

Joseph W. Calvin, E. B. Clark,

John Shelby, Thomas F. Smith

C. M. Beckworth, C. J. F. Allen,

J. R. Timberlake, G. Foley,

Stephen Skuler, Henry Smith,

A. W. Fringe, S. H. Curl

D.M. Crum James Holmes

Geo. W. Curl Thomas K. Barbee

N.W. Warfield E.W. Kerger

Ashley D. Hert J.T. Smith

William A. Smith

The Governor evidently agreed and granted Rhorer Pardon No. 383.

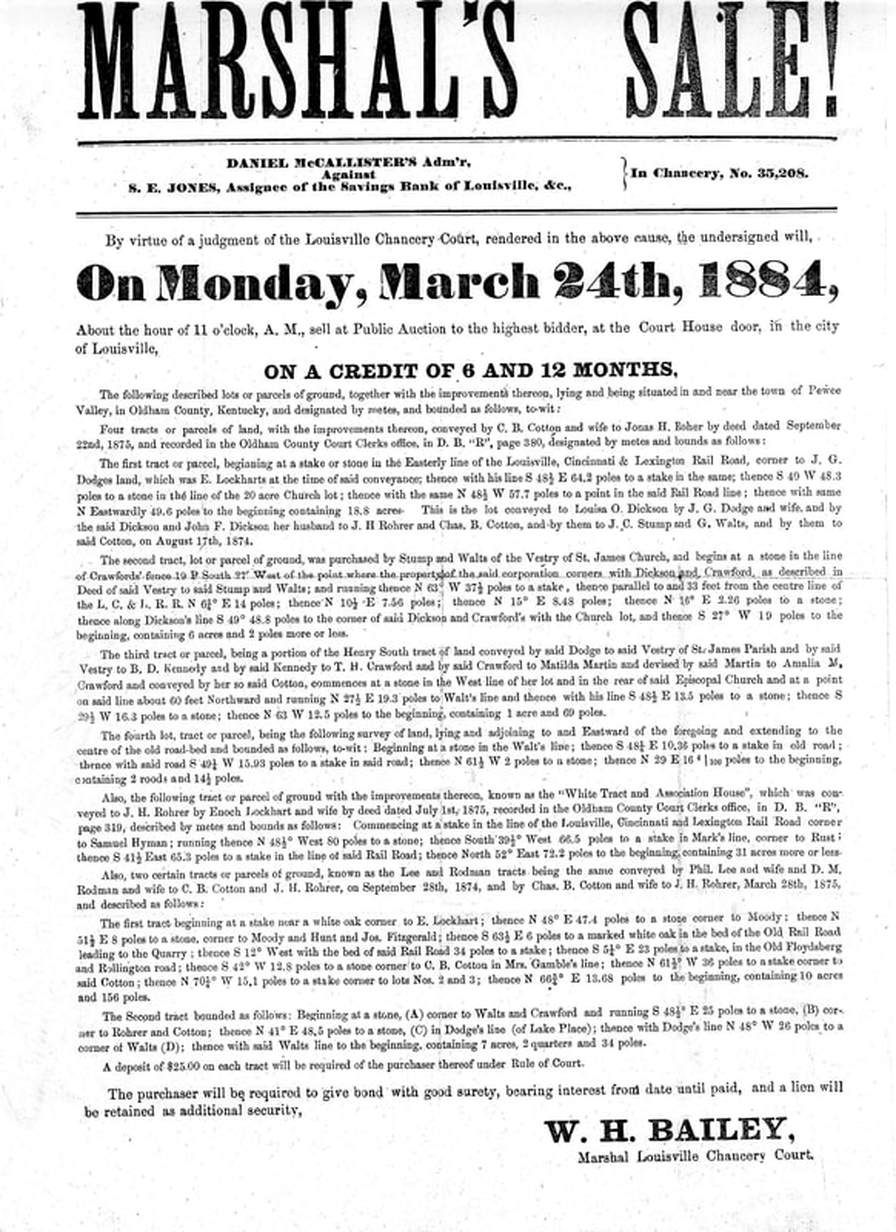

Rhorer's Pewee Valley properties went on the auction block at a Marshal's Sale on March 24, 1884. Many of them are within the Wooldridge Avenue-LaGrange Road historic area.

Related Links: