Pewee Valley Train Depot

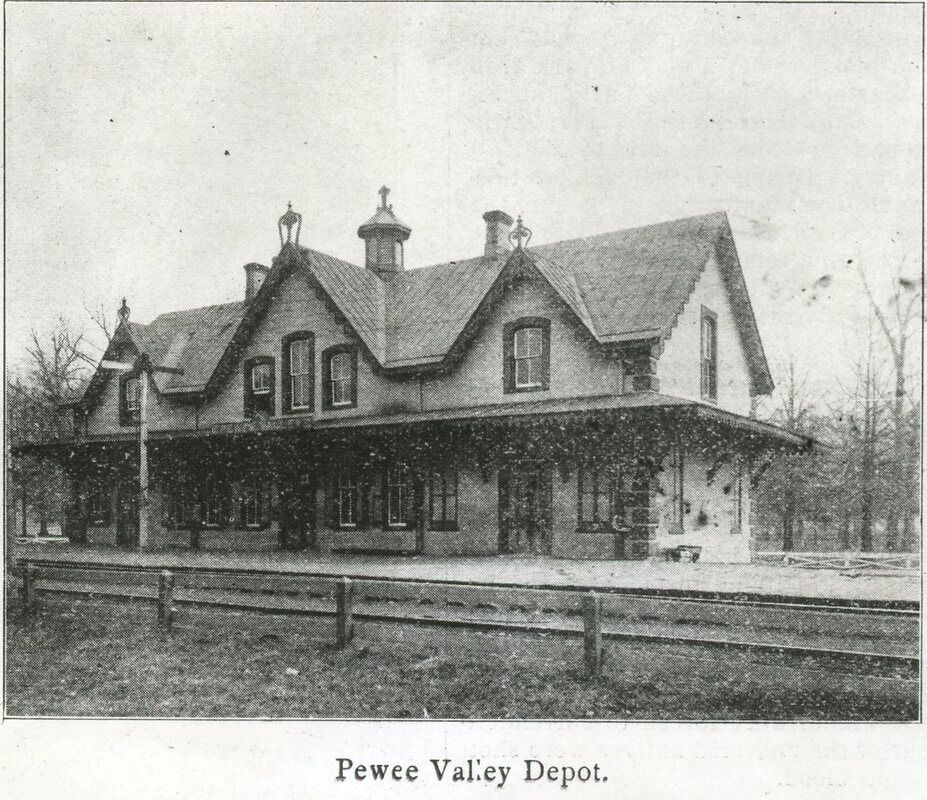

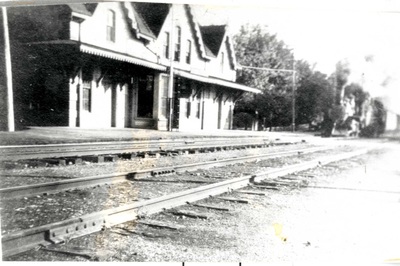

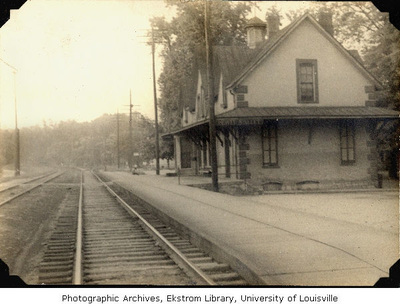

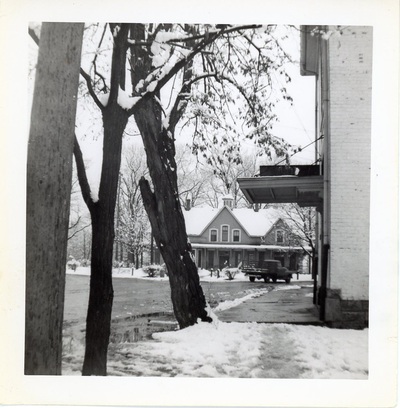

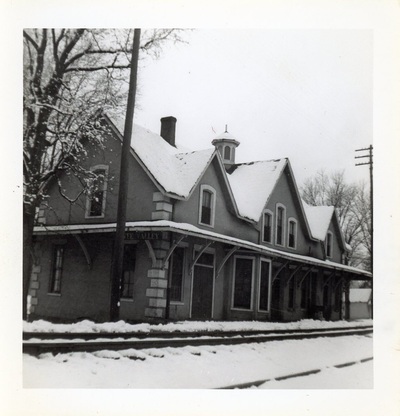

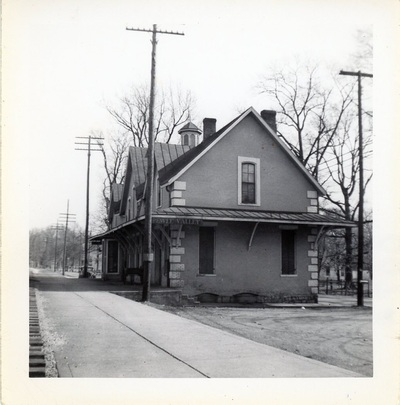

Above, opening day for the Pewee Valley Depot, 1867. From "Historic Pewee Valley," published by Historic Pewee Valley, Inc. in 1991. The photo was once owned by Mary G. Johnston and later appeared on the cover of the October 1934 L&N Railroad's employee magazine. Below, the other side of the depot where passengers entered and disembarked, presumably by Kate Matthews. From the Fox Studio Movie Scrapbook, Oldham County Historical Society.

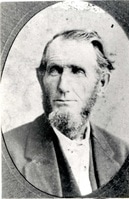

Henry Smith

Henry Smith

If not for the Louisville and Frankfort Railroad (L&F), Pewee Valley as we know it would never have existed. Rollington was the original settlement in this corner of Oldham County and was formally established as a town in 1847 by the Kentucky House of Representatives. Rollington was north of the city’s present center along the old Ballardsville Turnpike-Boonesboro Road (now Rollington Road), and served as a stopping point for people traveling between Middletown and Westport and Louisville and Brownsboro.

Construction of the L&F started in 1849 at Brook and Jefferson streets in Louisville, where the passenger station, roundhouse and train shed were located. By 1850, the line to LaGrange was finished and by August 1851, with completion of a bridge over the Kentucky River, service was available all the way from Louisville to the state capital in Frankfort. Katie S. Smith in "Pewee Valley: The Land of the Little Colonel" observed:

Providence, wearing the veil of destiny, prompted the laying of the railroad from Frankfort to Louisville through our sylvan glen. Service work trains were operating from LaGrange to Louisville in 1849. Passenger services started from Louisville to LaGrange in 1850. In 1854, possibly the first “commuter” train in the country, was inaugurated. “This train leaves LaGrange at 6:15 a.m. and arrives at Louisville at 7:40 a.m.; and returning leaves Louisville at 5 p.m. and reaches LaGrange at 6:40 p.m.” Many a city dweller was tempted to seek a home or summer residence amid the majestic splendor of (Pewee Valley’s) trees.

And the settlers came. In the vanguard were Henry Smith (December 4, 1802-1883), whose was a second-generation pioneer, and Thomas Smith (1792-1865), an early commuter who relied on the train to work at his rope factory in Louisville . Unlike the Smith Brothers of throat drop fame, however, Henry and Thomas weren’t related and their roles as city forefathers were decidedly different.

Henry was born and raised in Rollington and conducted early road surveys for the county. In 1837, he bought a farm that ran from present-day Central Avenue to Houston Lane, where he and his wife, Susan Wilson Smith, raised three children: Charles Franklin, William Alexander and Sarah Emma. Henry sold tracts of his original farm – an acre to the railroad in 1856, as well as tracts to other settlers; helped establish the town’s first post office; bought 220 acres on the south side of the tracks in 1866 to develop Pewee Valley into a real town; and was the driving force behind the establishment of Pewee Valley Cemetery.

Construction of the L&F started in 1849 at Brook and Jefferson streets in Louisville, where the passenger station, roundhouse and train shed were located. By 1850, the line to LaGrange was finished and by August 1851, with completion of a bridge over the Kentucky River, service was available all the way from Louisville to the state capital in Frankfort. Katie S. Smith in "Pewee Valley: The Land of the Little Colonel" observed:

Providence, wearing the veil of destiny, prompted the laying of the railroad from Frankfort to Louisville through our sylvan glen. Service work trains were operating from LaGrange to Louisville in 1849. Passenger services started from Louisville to LaGrange in 1850. In 1854, possibly the first “commuter” train in the country, was inaugurated. “This train leaves LaGrange at 6:15 a.m. and arrives at Louisville at 7:40 a.m.; and returning leaves Louisville at 5 p.m. and reaches LaGrange at 6:40 p.m.” Many a city dweller was tempted to seek a home or summer residence amid the majestic splendor of (Pewee Valley’s) trees.

And the settlers came. In the vanguard were Henry Smith (December 4, 1802-1883), whose was a second-generation pioneer, and Thomas Smith (1792-1865), an early commuter who relied on the train to work at his rope factory in Louisville . Unlike the Smith Brothers of throat drop fame, however, Henry and Thomas weren’t related and their roles as city forefathers were decidedly different.

Henry was born and raised in Rollington and conducted early road surveys for the county. In 1837, he bought a farm that ran from present-day Central Avenue to Houston Lane, where he and his wife, Susan Wilson Smith, raised three children: Charles Franklin, William Alexander and Sarah Emma. Henry sold tracts of his original farm – an acre to the railroad in 1856, as well as tracts to other settlers; helped establish the town’s first post office; bought 220 acres on the south side of the tracks in 1866 to develop Pewee Valley into a real town; and was the driving force behind the establishment of Pewee Valley Cemetery.

Thomas Smith

Thomas Smith

Thomas and his wife, Nannette Price Smith, were among the first settlers who arrived with the railroad. The Thomas Smiths, along with the James Alexander Millers, helped attract many writers and other prominent people to the area. Thomas had several careers, but his first was in the printing trade, as editor and publisher of two Lexington newspapers. He also served -- very briefly -- as Pewee Valley's fourth postmaster at the outbreak of the Civil War. He and Nannette built three different homes here, including Woodside, which still stands on Central Avenue today, and was the first sight that greeted visitors when they stepped off the train.

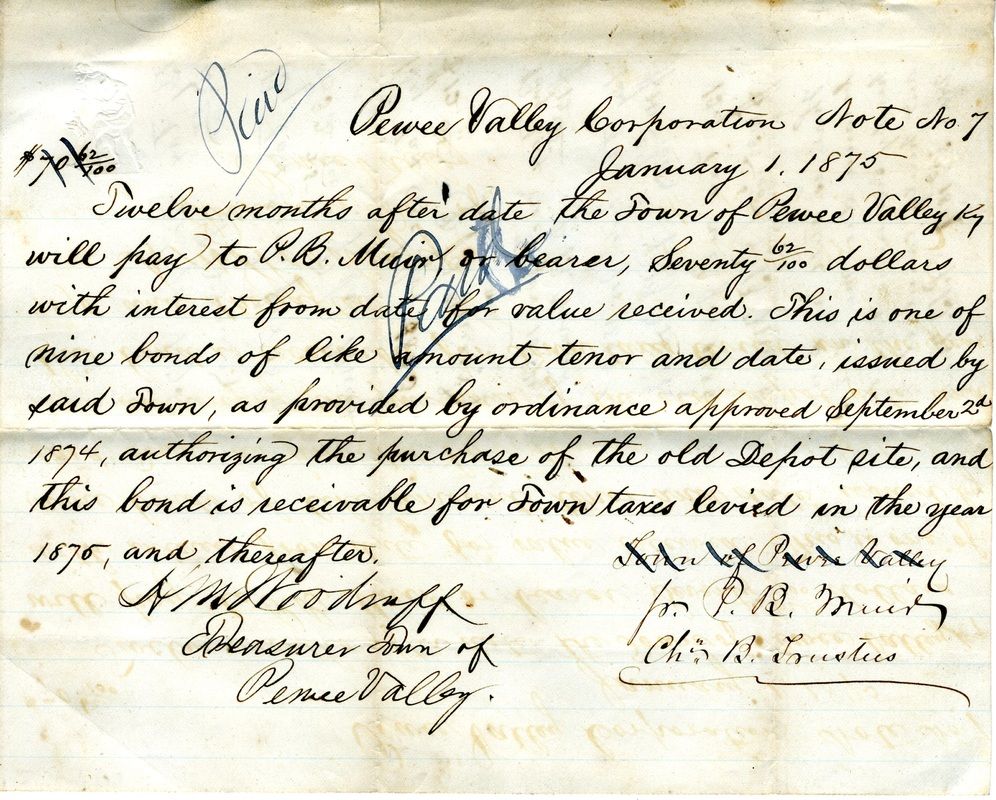

Although Pewee Valley was a regular stop on the L&F’s commuter line, it wasn’t until 1867 that the town had a true depot. That was when a group of citizens got together and paid to have one built. They included John M. Armstrong* of Valhalla; Woodford H. Dulaney of Tuliphurst; Jonas H. Rhorer of Locust; the Rev. J. L. McKee of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church; Henry M. Woodruff, who owned the mercantile at the corner of Central and Railroad avenues; and Orville N. Truman, who lived in what’s now known as the Truman-Miller-Richard house. In 1874, the city sold bonds to purchase the depot. Judge P.B. Muir of Oaklea was one of the bond purchasers. However, on September 22, 1879, for the sum of $1.00, Pewee Valley returned the deed to them, pending the sale of the railroad and depot to the K&I in 1881.

|

|

For years the station functioned as both a transportation hub and a community center. The end of the line came in 1933, when passenger service came to a halt. On November 3, 1958, every member of Pewee Valley's Town Board signed a letter to the Vice President of the L&N, asking them to tear down the old depot to straighten LaGrange Road. Their petition was answered in March 1960, when the station was demolished. On August 6, 1962, the city minutes reported, "The long-sought straightening of the curve in LaGrange Road around the site of the former depot has now been accomplished." Today, a red caboose near the town square is the only reminder of the gothic brick depot, which once dominated the view down Central Avenue and was such a beehive of social activity. The caboose is named for John Frith Stewart, a former Pewee Valley mayor who served four terms between 1970 and 1985. The L&N donated the caboose to the city in 1971, in memory of Mayor Stewart’s father, Charles Stewart, who retired from the railroad. Today, it symbolizes the key role train service played during the town’s formative years. |

This story on the depot's demolition, written by Melville O. Briney for the Courier-Journal (date unknown), offers a glimpse of the station's past and the memories it represented to people who summered in Pewee Valley at the turn of the 20th century or were Annie Fellows Johnston fans:

Pewee Valley Train Station

A story in the newspaper last week told of the razing of the Pewee Valley station. The 93-year-old structure, according to the Times was "a symbol of what long time Pewee residents consider the Oldham County town's finest period -- 1867, when the depot opened, through the early 1900s." Victorian gingerbread that once proudly adorned its front had been removed in later years, but otherwise its appearance must have been much the same as on the gala opening day. The automobile put an end to its usefulness by 1933, and since then no trains have stopped there.

Miss Mary G. Johnston, daughter of Annie Fellows Johnston, author of the "Little Colonel" books, recalls the station in its heyday when "each evening it was a scene of great excitement when horse-drawn rigs met the men as they returned from their offices in Louisville. And ice-cream never tasted as good as it did on the station platform with cinders in it."

I have never been a resident of Pewee Valley. In fact, I have been there very few times in my life. But to every Louisvillian of the female gender and my vintage, Pewee Valley is surely a perennial land of romance peopled still by Mrs. Johnston's unforgettable characters.

Nothing that happens there, even the razing of an antiquated railroad station, can leave me quite untouched. For here was the opening scene of "Two Little Knights of Kentucky." Into "the little country depot" where "a long row of icicles hung from the eaves" and the wind "shivered down the long stovepipe inside the waiting room" came the two McIntryre boys, Malcolm and Keith, to bring their adventure with Jonesy and the bear.

Surely, to this same station, must have come Betty, Joyce and rich Eugenia to join the Little Colonel's house party. On this same platform, suitcase in hand, must have stepped wayward Ida Shane on her way to boarding school in Lloydsborough Valley. And from this station, too, a radiant Lloyd must have set forth with Rob Moore on her honeymoon in that most romantic book of them all, "The Little Colonel's Knight Comes Riding."

When Mrs. Johnston was asked by countless readers if Lloydsborough Valley was a real place, she wrote in 1929:

"You will find it on a map of Oldham County under the name of Pewee Valley, but will still never find it now along any road whatsoever where you may go on a pilgrimage, for the years have stolen its pristine charm and it is no longer a storybook sort of place.

"But 30 years ago, wandering down its shady avenues was like stepping between the covers of an old romance. One had only to stroll past the little country post office to feel the glamour of the place and meet a host of interesting characters. In those days the post office, at nine o'clock of a summer morning, was the social center for an animated half hour or more.

"The smart equipages of summer residents were drawn up to the front of it. Old family carryalls loaded with children in care of black mammies joined the procession, and pretty girls and their escorts on horseback drew rein in the shade of locusts arching the road...”

Pewee Valley Train Station

A story in the newspaper last week told of the razing of the Pewee Valley station. The 93-year-old structure, according to the Times was "a symbol of what long time Pewee residents consider the Oldham County town's finest period -- 1867, when the depot opened, through the early 1900s." Victorian gingerbread that once proudly adorned its front had been removed in later years, but otherwise its appearance must have been much the same as on the gala opening day. The automobile put an end to its usefulness by 1933, and since then no trains have stopped there.

Miss Mary G. Johnston, daughter of Annie Fellows Johnston, author of the "Little Colonel" books, recalls the station in its heyday when "each evening it was a scene of great excitement when horse-drawn rigs met the men as they returned from their offices in Louisville. And ice-cream never tasted as good as it did on the station platform with cinders in it."

I have never been a resident of Pewee Valley. In fact, I have been there very few times in my life. But to every Louisvillian of the female gender and my vintage, Pewee Valley is surely a perennial land of romance peopled still by Mrs. Johnston's unforgettable characters.

Nothing that happens there, even the razing of an antiquated railroad station, can leave me quite untouched. For here was the opening scene of "Two Little Knights of Kentucky." Into "the little country depot" where "a long row of icicles hung from the eaves" and the wind "shivered down the long stovepipe inside the waiting room" came the two McIntryre boys, Malcolm and Keith, to bring their adventure with Jonesy and the bear.

Surely, to this same station, must have come Betty, Joyce and rich Eugenia to join the Little Colonel's house party. On this same platform, suitcase in hand, must have stepped wayward Ida Shane on her way to boarding school in Lloydsborough Valley. And from this station, too, a radiant Lloyd must have set forth with Rob Moore on her honeymoon in that most romantic book of them all, "The Little Colonel's Knight Comes Riding."

When Mrs. Johnston was asked by countless readers if Lloydsborough Valley was a real place, she wrote in 1929:

"You will find it on a map of Oldham County under the name of Pewee Valley, but will still never find it now along any road whatsoever where you may go on a pilgrimage, for the years have stolen its pristine charm and it is no longer a storybook sort of place.

"But 30 years ago, wandering down its shady avenues was like stepping between the covers of an old romance. One had only to stroll past the little country post office to feel the glamour of the place and meet a host of interesting characters. In those days the post office, at nine o'clock of a summer morning, was the social center for an animated half hour or more.

"The smart equipages of summer residents were drawn up to the front of it. Old family carryalls loaded with children in care of black mammies joined the procession, and pretty girls and their escorts on horseback drew rein in the shade of locusts arching the road...”

Views of the Pewee Valley Depot Through the Years

On August 21, 1878, popular Louisville songwriter Will S. Hayes wrote a poem capturing the reason so many men were willing to make the 30-45-minute commute by train each day to their jobs in Louisville:

“Highland,” Pewee Valley

The rosy-cheeked apple hung down by the stem,

The song birds were waking the beautiful morn,

And dew-drops were trembling, each like a gem,

That shone on the blades of the green, waving corn.

The sun, in its chariot, mounted the sky,

The cow bells made music upon the still air;

In green shades of “Highland” the hours flew by,

And I thought, if there’s pleasure on earth, it is there.

I sat in the shade of an old beech tree,

My heart was contented; my life was a bliss.

I thought, as the birds sang so sweetly for me,

What happier life could I ask for than this?

The air so refreshing, and nature so still,

The fragrance of roses, bespattered with dew,

The clover-decked carpet of that Kentucky hill ---

I could live here forever in joy, couldn’t you?

But each day takes me back to the hot, dusty street

Of the bustling city to wear away my life

Amid business and turmoil, where each one I meet

Seems deeply engaged in a struggle of strife.

Good-bye then, sweet, “Highland!” I’ll leave all I love

To enjoy all the pleasures, the joys and the bliss

Of a home that’s akin to the one up above,

Made pure, when I return, by a wife’s welcome kiss.

*According to the Beers and Lanagan atlas of Pewee Valley published in 1879, Valhalla was a large property located on the western side of Ashwood (now Ash) Avenue and owned by J.M. Armstrong. An ad in the May 11, 1863 issue of the Louisville Daily Democrat shows that Armstrong owned a Louisville clothing store at the corner of Fourth and Main streets, opposite the National Hotel, known as Tower Palace “where men, women and children flock in crowds.”

“Highland,” Pewee Valley

The rosy-cheeked apple hung down by the stem,

The song birds were waking the beautiful morn,

And dew-drops were trembling, each like a gem,

That shone on the blades of the green, waving corn.

The sun, in its chariot, mounted the sky,

The cow bells made music upon the still air;

In green shades of “Highland” the hours flew by,

And I thought, if there’s pleasure on earth, it is there.

I sat in the shade of an old beech tree,

My heart was contented; my life was a bliss.

I thought, as the birds sang so sweetly for me,

What happier life could I ask for than this?

The air so refreshing, and nature so still,

The fragrance of roses, bespattered with dew,

The clover-decked carpet of that Kentucky hill ---

I could live here forever in joy, couldn’t you?

But each day takes me back to the hot, dusty street

Of the bustling city to wear away my life

Amid business and turmoil, where each one I meet

Seems deeply engaged in a struggle of strife.

Good-bye then, sweet, “Highland!” I’ll leave all I love

To enjoy all the pleasures, the joys and the bliss

Of a home that’s akin to the one up above,

Made pure, when I return, by a wife’s welcome kiss.

*According to the Beers and Lanagan atlas of Pewee Valley published in 1879, Valhalla was a large property located on the western side of Ashwood (now Ash) Avenue and owned by J.M. Armstrong. An ad in the May 11, 1863 issue of the Louisville Daily Democrat shows that Armstrong owned a Louisville clothing store at the corner of Fourth and Main streets, opposite the National Hotel, known as Tower Palace “where men, women and children flock in crowds.”

Related Links