Truman-Miller-Richard House: The Truman & Miller Years, ca. 1870-1915

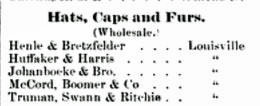

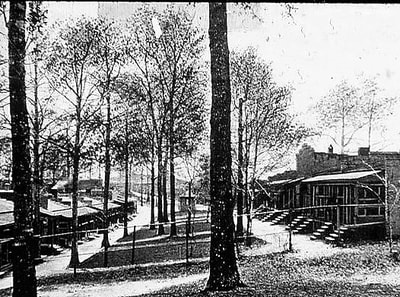

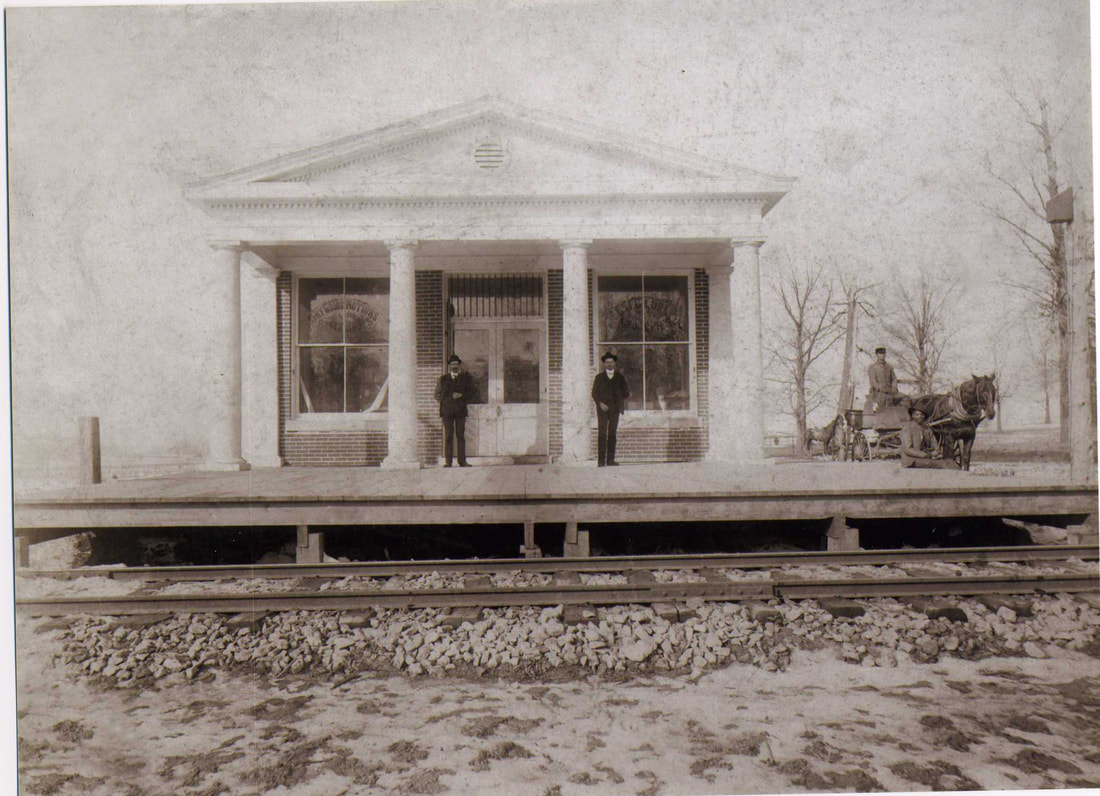

This old photo, taken from Ann Montgomery's "35 Landmark Homes of Pewee Valley," shows the Truman-Miller-Richard House as it looked before the exterior was remodeled three times.

Of Pewee Valley's many National Register properties, the Truman-Miller-Richard House on Wooldridge Place has undergone the most radical change in appearance over its lifetime. When it was built by Orville Truman ca. 1869-70, the house was Victorian in style, according to this well-researched article about the property from the 1995 Bellarmine Show House program:

... The construction of the house reflects the history of its nineteenth century origins. Rapid industrial and urban expansion in this era led city residents to yearn for the fresh air, peace and simple life of the countryside. The development of rural retreats was made possible by the construction of railroads, such as the line between Pewee Valley and Louisville built in the early 1850s. In September 1869, Orville Truman, a Louisville dry good merchant, born in New Hampshire, bought five and a half acres of land from Charles Cotton, a Pewee Valley resident who practiced law in Louisville, and an adjoining, just under five acres from the Gallagher family ... The original two and one-half story house, built in the popular Queen Anne Victorian style, had a parlor, reception room, dining room and kitchen on the first floor, four bedrooms on the second floor, with three small rooms above. Sheathed in five-inch painted poplar clapboard, with decorative areas of cedar shakes and fish scale shingles, the house had a cross-gabled shingle roof with a dominant front gable and an octagonal tour in the rear. Overhanging eaves were ornamented by dentil molding. Summer breezes were captured with sleeping porches on each side of the second floor and by the roofed wrap-around porch attached directly to the parlor, which also had doors on each side leading to, and catching fresh air, from the porch.

Major changes to its exterior occurred in the 1940s, 1990s and around 2012. Today, the original Queen Anne wraparound porch is gone, replaced by a two-story front porch addition with Neoclassical Southern-style columns. Faux-stone has replaced the wood siding. Gone, too, are the original grounds. The once 10-acre estate is now a small subdivision.

The Truman Years: 1870-1892

|

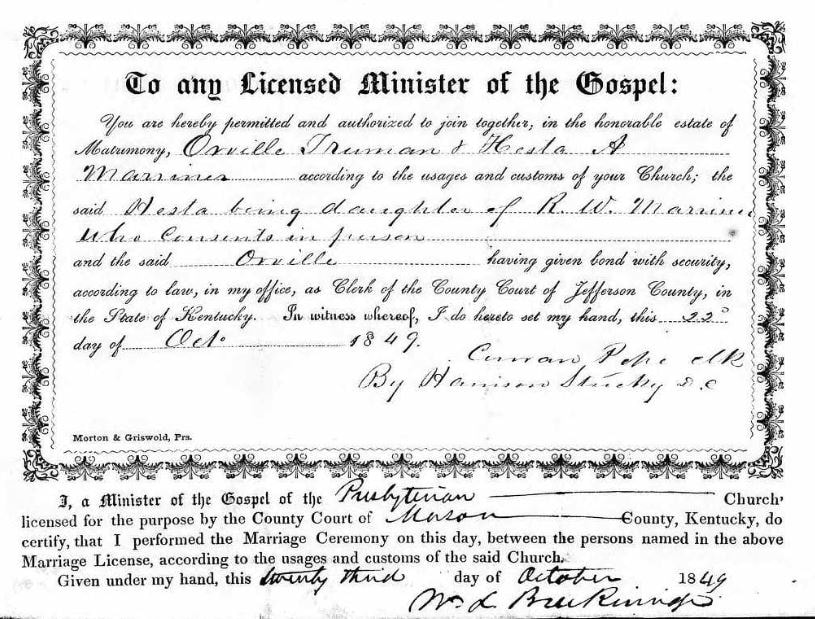

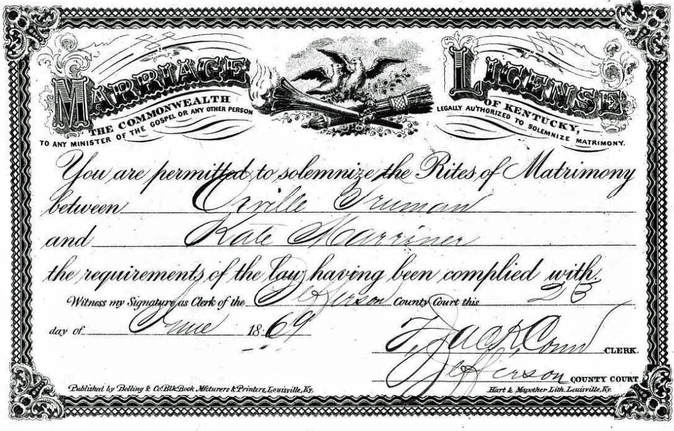

When Orville and Catharine "Kate" Truman purchased their Pewee Valley property, they were newlyweds. It was a second marriage for Orville, a first for Kate, who was 20 years younger than her new husband. They were married on June 23, 1869 in Louisville, and just three months later, bought the two, five-acre tracts for their new home in Pewee Valley. Orville's first wife was Kate's older sister, Hesta Ann "Hetty" Marriner, whom he married on October 23, 1849. She died on October 18, 1864, leaving behind five children ranging in age from 14 to infancy:

|

There is some evidence to indicate that Orville was living in Pewee Valley prior to building his new home. He was one of the seven residents who paid to have the Pewee Valley Train Depot built in 1867.

The Marriner Family

Orville Truman's in-laws, Reece Wolfe and Ann West Marriner, originally haled from Lewes, Delaware, located on the bay in eastern Sussex County. Based on the 1850 census, they arrived in Kentucky between 1836 and 1838. Their first four children were born in Delaware and their last three in Kentucky:

- Hesta Ann "Hetty" Marriner Truman, age 22, born in Delaware

- Sarah "Sallie" Marriner, age 18, born in Deleware

- Elizabeth R. Marriner, age 16, born in Delaware

- Reece G. Marriner, age 14, born in Delaware

- William McCain Marriner, age 12, born in Kentucky

- Catharine "Kate" Marriner, age 10, born in Kentucky

- Mary Marriner, age 7, born in Kentucky

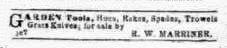

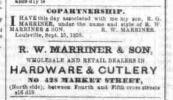

By 1843, Reece had opened a hardware and cutlery store in Louisville. Located on Market Street, it remained in business over 20 years. According to a biography of his grandson, Harry C. Truman, published in “Kentucky: A History of the State,” by Perrin, Battle, Kniffin, 8th ed. (Jefferson Co.; 1888), Reece Marriner was ".. one of the leading hardware merchants of Louisville ..." in his day. What eventually led to the firm's demise was Reece's retirement in 1861 and the death of his son and successor, Reece G. Marriner, in 1863.

R.W. Marriner Hardware Store Ads & Announcements

The Truman Family

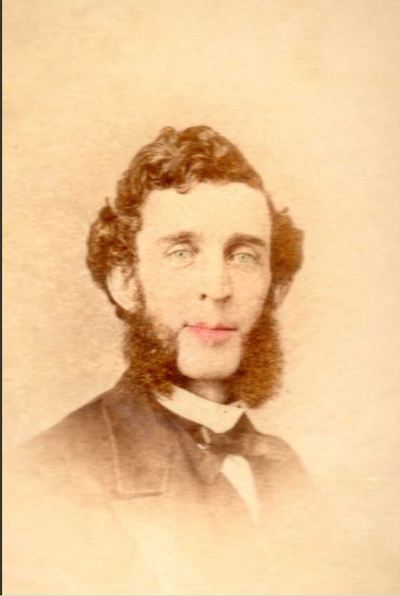

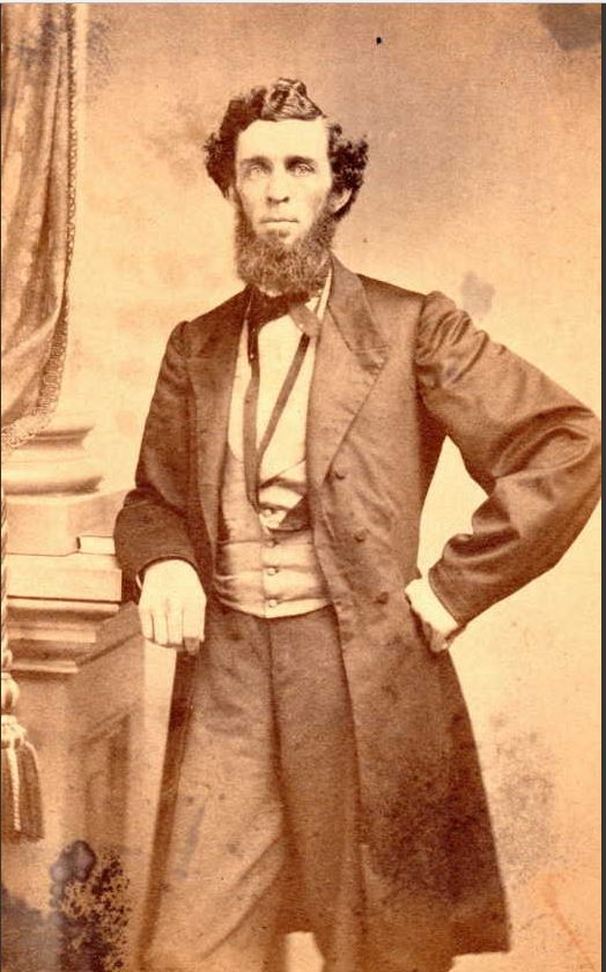

Orville Truman from ancestry.com

Orville Truman from ancestry.com

Unlike his in-laws, Orville Truman was a Northerner. Born March 10, 1824 in Lebanon, New Hampshire, he was the son of Thomas and Sally Lathrop Truman. His father was a cabinetmaker by trade. However, Orville barely knew his parents. Both died in 1827, when he was just three years old.

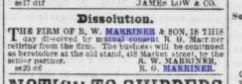

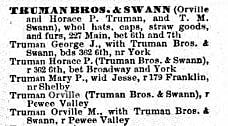

Exactly when he emigrated to Louisville is unknown. The first time he appears in Kentucky records is 1849, when he married Hetty Marriner. During the early years of their marriage, they lived with her parents and Orville was employed as a clerk, according to the 1850 census. A decade later, the 1860 census reported that Orville was head of his own household, was employed as a merchant, and had a personal estate valued at $29,000 (about $817,000 today). According to the "The Louisville Directory and Business Advertiser for 1860," Orville had gone into the hat and cap business with Michael Fielding and at that time was operating a store at 616 W. Main Street in downtown Louisville.

Also by 1860, his brother, Horace Parkhurst Truman, along with his sister-in-law Elizabeth Flanders, and his niece and nephew, Mable and George, had left New Hampshire and moved to Louisville. The brothers eventually went into business together with Aleck Craig, who had been a major player in Louisville's hat, fur and cape business since 1851. With Craig's death in 1869, the firm's name changed from Craig, Truman & Co. to Truman Bros. & Swann.

Exactly when he emigrated to Louisville is unknown. The first time he appears in Kentucky records is 1849, when he married Hetty Marriner. During the early years of their marriage, they lived with her parents and Orville was employed as a clerk, according to the 1850 census. A decade later, the 1860 census reported that Orville was head of his own household, was employed as a merchant, and had a personal estate valued at $29,000 (about $817,000 today). According to the "The Louisville Directory and Business Advertiser for 1860," Orville had gone into the hat and cap business with Michael Fielding and at that time was operating a store at 616 W. Main Street in downtown Louisville.

Also by 1860, his brother, Horace Parkhurst Truman, along with his sister-in-law Elizabeth Flanders, and his niece and nephew, Mable and George, had left New Hampshire and moved to Louisville. The brothers eventually went into business together with Aleck Craig, who had been a major player in Louisville's hat, fur and cape business since 1851. With Craig's death in 1869, the firm's name changed from Craig, Truman & Co. to Truman Bros. & Swann.

Truman & Swan Ads & Announcements

Civil War Loyalties

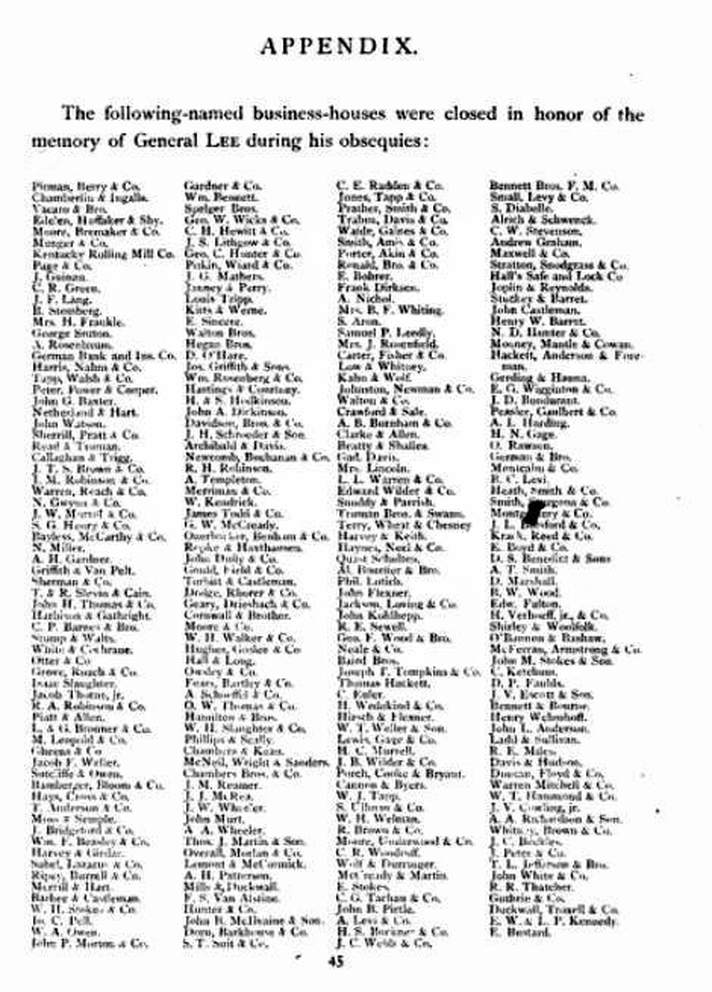

Appendix of "Robert E. Lee: In Memoriam, a Tribute of Respect Offered by the Citizens of Louisville," (J.P. Morton, Louisville; 1870)

Appendix of "Robert E. Lee: In Memoriam, a Tribute of Respect Offered by the Citizens of Louisville," (J.P. Morton, Louisville; 1870)

Surprisingly for a man born above the Mason-Dixon Line, Orville Truman owned slaves. According to the 1860 slave registry, he owned three, all female, ages 40, 50 and 75. Whether they worked in his store or his home is unknown. Many Louisville businessmen, including Peweean William H. Walker, who owned a restaurant and liquor store, relied at least partially on slave labor to keep the register ringing.

While Orville didn't fight in the war, one of his brothers-in-law did. William McCain Marriner enlisted in the Confederate Army and served in Company H, 1st Regiment of the Kentucky Infantry. According to Wikipedia:

The 1st Kentucky Infantry was organized in August 1861, by consolidation of two battalions of Kentucky infantry. One battalion was under the command of Blanton Duncan and the other was under the command of John Pope. The regiment had ten companies. The two battalions arrived in Virginia at Harper's Ferry, later moving to Winchester. The two battalions moved with Joe Johnston's Army of the Shenandoah to join Beauregard's Army of the Potomac at Manassas Junction, but arrived the day following the First Battle of Bull Run under the command of Major Thomas Claiborne. With Duncan, who submitted his resignation on August 13, gone, the two battalions merged. In August a third battalion of three companies, then around New Port News, Va., and augmented by a company of Kentuckians from the 1st Louisiana, were ordered by Richmond to join with the six companies then at Manassas Junction. Lieut. Col. Thomas Hart Taylor was assigned to command of the regiment on August 7, 1861. Taylor was later promoted to Colonel and remained in command until the unit was mustered out.

The regiment was assigned to a brigade under the command of J.E.B. Stuart and participated in the Battle of Dranesville. In mid-1862, the regiment was ordered to Richmond, Virginia and later participated in the Battle of Yorktown. Following the battle, the 1st Kentucky Infantry was ordered back to Richmond where it remained until its twelve-month enlistment expired. The men were mustered out of service on March 13 and 14, 1862.

William was mustered into the Confederate Army as a sergeant and mustered out as a captain. After leaving the military, he served as the principal of Louisville's 2nd Ward School for 43 years.

One other piece of evidence that Orville Truman's Civil War sympathies were likely with the South is an 1870 book published by J.P. Morton called "Robert E. Lee: In Memoriam, a Tribute of Respect Offered by the Citizens of Louisville." The book included a list of local businesses that closed for General Lee's funeral. Among those listed: Truman Bros. & Swann and the William H. Walker Co.

While Orville didn't fight in the war, one of his brothers-in-law did. William McCain Marriner enlisted in the Confederate Army and served in Company H, 1st Regiment of the Kentucky Infantry. According to Wikipedia:

The 1st Kentucky Infantry was organized in August 1861, by consolidation of two battalions of Kentucky infantry. One battalion was under the command of Blanton Duncan and the other was under the command of John Pope. The regiment had ten companies. The two battalions arrived in Virginia at Harper's Ferry, later moving to Winchester. The two battalions moved with Joe Johnston's Army of the Shenandoah to join Beauregard's Army of the Potomac at Manassas Junction, but arrived the day following the First Battle of Bull Run under the command of Major Thomas Claiborne. With Duncan, who submitted his resignation on August 13, gone, the two battalions merged. In August a third battalion of three companies, then around New Port News, Va., and augmented by a company of Kentuckians from the 1st Louisiana, were ordered by Richmond to join with the six companies then at Manassas Junction. Lieut. Col. Thomas Hart Taylor was assigned to command of the regiment on August 7, 1861. Taylor was later promoted to Colonel and remained in command until the unit was mustered out.

The regiment was assigned to a brigade under the command of J.E.B. Stuart and participated in the Battle of Dranesville. In mid-1862, the regiment was ordered to Richmond, Virginia and later participated in the Battle of Yorktown. Following the battle, the 1st Kentucky Infantry was ordered back to Richmond where it remained until its twelve-month enlistment expired. The men were mustered out of service on March 13 and 14, 1862.

William was mustered into the Confederate Army as a sergeant and mustered out as a captain. After leaving the military, he served as the principal of Louisville's 2nd Ward School for 43 years.

One other piece of evidence that Orville Truman's Civil War sympathies were likely with the South is an 1870 book published by J.P. Morton called "Robert E. Lee: In Memoriam, a Tribute of Respect Offered by the Citizens of Louisville." The book included a list of local businesses that closed for General Lee's funeral. Among those listed: Truman Bros. & Swann and the William H. Walker Co.

Life in Pewee Valley

1870 was a banner year for the Trumans. They were newly married with a brand new home in one of Louisville's loveliest and reputedly healthiest suburbs. Kate's parents had also left the city's squalor and were living nearby. While no doubt saddened by the death of his partner Aleck Craig the previous year, his loss opened up opportunities for Orville both in the business world and in his newly-adopted hometown. When Pewee Valley was incorporated by the Kentucky Legislature on March 14, 1870, Orville was among its first trustees:

... § 2. That Orville Truman, William Keeley, John M. Armstrong, Milton M. Rhorer, Charles B. Cotton, James G. Dodge, and Henry Smith, are hereby appointed trustees of said town, to remain in office until the first Monday in August, one thousand eight hundred and seventy; on which day, and on the first Monday of said month in each succeeding year, the qualified voters of said town shall meet at such place as may be designated by the trustees of said town, and choose by vote, viva voce, seven persons for trustees, to serve for one year, and until their successors are elected and qualified. Any vacancies occurring in the board by resignation, death, removal, or other cause, shall be filled by the board of trustees...

Fortune, however, had quit smiling on them by year's end. Kate's father, Reece Wolfe Marriner, died on December 10, 1870. In the spring, Kate learned she was pregnant with her first child. Orville never lived to see his youngest son. He died in October 1871. Laurence Stuart Truman was born a month later on November 16.

Orville's will is on file at the Oldham County Courthouse in LaGrange, Ky. Thanks to Oldham County Clerk Julia K. Barr for providing a copy to the Pewee Valley Historical Society:

Know all men by these presents that I the undersigned Orville Truman of Pewee Valley Oldham County Kentucky have ordained and published the following as my last Will and Testament. To Wit

1st I give and bequeath to my beloved wife Kate M Truman for and during her Life or Widowhood all my Estate real personal and mixed after the payment of my Just debts and funeral Expenses.

2nd After the death or marriage of my said wife my entire Estate shall pass into the hands of my Brother Horace P. Truman and my Son Harold Clarence Truman as trustees and to be distributed as follows to wit on the event of the death of my wife they are to distribute it finally between my Children share & share alike in the event of the marriage of my said wife these said trustees are to hand over to her one-third of my Estate for life and to divide the residue ... among my Children the one third to be given her to be severally divided among my Children at her death.

3rd In the Event of the death of any children the descendants of such child if any shall receive the Estate the parent would have received if living

4th I desire that my wife shall retain and occupy my residence in Pewee Valley as a home for herself and Children she may however in her discretion sell and convey said property and hold the proceeds of such sale as she will hold the residence under the 1st and 2nd Articles of the Will.

5th The foregoing devices and bequeath to my wife are charged with the support and Education of my Infant Children until their majority but the purchases of the property or Estate may be sold by her is not to be bound to look to the application of the proceeds of such sale.

6th I direct that my Estate excluding my residence and personally thereon and Connected therewith be converted by my Executrix into good and safe Bonds and Stocks paying Interest Semiannually. If after the support of my wife and the support and Education of my Infant Children a surplus shall remain unexpounded on the Interest aforesaid my wife may advance the same to such of my children as in her Judgment may most need and desire It. The child or Children to whom such advancement shall be made must be charged with the same and required to account therefore in the final settlement and distribution of my Estate.

7th I devise to my Mother Fifty Dollars each year during her life to be paid her by my Executrix in seminannual installments

8th Should my Colorado Mining Stock ever yield a revenue I devise said revenue to my Children and direct my Executrix to pay the same over to them in Equal Shares

9th I do nominate constitute and appoint my wife Kate M Truman Executrix of this my last will and testament and having full confidence in her I direct she shall not be required to give any surety as such.

In Testimony of all which I hereto subscribe my name this the 1st day of May 1871.

Orville Truman

Attest

G. H. Stewart

P.B. Muir

Know all men by these presents that I the undersigned Orville Truman of Pewee Valley Oldham County Kentucky have ordained and published the following as my last Will and Testament. To Wit

1st I give and bequeath to my beloved wife Kate M Truman for and during her Life or Widowhood all my Estate real personal and mixed after the payment of my Just debts and funeral Expenses.

2nd After the death or marriage of my said wife my entire Estate shall pass into the hands of my Brother Horace P. Truman and my Son Harold Clarence Truman as trustees and to be distributed as follows to wit on the event of the death of my wife they are to distribute it finally between my Children share & share alike in the event of the marriage of my said wife these said trustees are to hand over to her one-third of my Estate for life and to divide the residue ... among my Children the one third to be given her to be severally divided among my Children at her death.

3rd In the Event of the death of any children the descendants of such child if any shall receive the Estate the parent would have received if living

4th I desire that my wife shall retain and occupy my residence in Pewee Valley as a home for herself and Children she may however in her discretion sell and convey said property and hold the proceeds of such sale as she will hold the residence under the 1st and 2nd Articles of the Will.

5th The foregoing devices and bequeath to my wife are charged with the support and Education of my Infant Children until their majority but the purchases of the property or Estate may be sold by her is not to be bound to look to the application of the proceeds of such sale.

6th I direct that my Estate excluding my residence and personally thereon and Connected therewith be converted by my Executrix into good and safe Bonds and Stocks paying Interest Semiannually. If after the support of my wife and the support and Education of my Infant Children a surplus shall remain unexpounded on the Interest aforesaid my wife may advance the same to such of my children as in her Judgment may most need and desire It. The child or Children to whom such advancement shall be made must be charged with the same and required to account therefore in the final settlement and distribution of my Estate.

7th I devise to my Mother Fifty Dollars each year during her life to be paid her by my Executrix in seminannual installments

8th Should my Colorado Mining Stock ever yield a revenue I devise said revenue to my Children and direct my Executrix to pay the same over to them in Equal Shares

9th I do nominate constitute and appoint my wife Kate M Truman Executrix of this my last will and testament and having full confidence in her I direct she shall not be required to give any surety as such.

In Testimony of all which I hereto subscribe my name this the 1st day of May 1871.

Orville Truman

Attest

G. H. Stewart

P.B. Muir

Kate and the children remained in Pewee Valley until October 1892, when she sold the house to Samuel and Henrietta Miller. At the time of the 1900 census, she, stepson Reece William and son Laurence, were living in Louisville with her widowed older sister, Sarah Gardner, and Sarah's two children. Kate died in New Albany, Indiana on October 17, 1913.

The Miller Years: 1892-1915

|

|

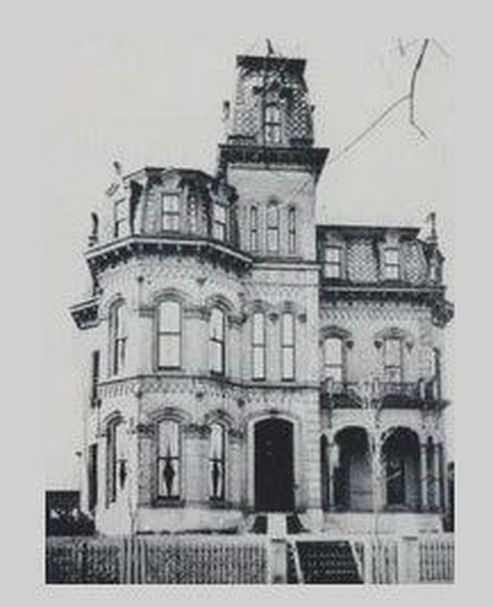

When the Millers purchased the house in 1892, they had no plans to live in it full-time. They already owned a magnificent mansion on Louisville's fashionable Fourth Street. What they wanted was a country retreat.

An excellent description of what the house looked like after the Millers finished renovating and modernizing it appeared in the August 11, 1895 Courier-Journal in a story called "Pewee Valley Homes: Ideal Resting Places Owned by Fortunate Louisville People -- Glimpses of Favored Spots": ... Mrs. Samuel A. Miller has one of the most complete and modern homes. The house is new, but the grounds have many grand old trees and shrubbery that make it inviting. Mrs. Miller's family spend the summer there, but return to the city in the fall. The gates open from the main road, and there is a clump of pine trees that are over fifty years old and are the admiration of all visitors to Pewee Valley. There are various flower beds in which sweet peas, geraniums and various flowers are growing. The stables and outbuildings are in fine repair, and a horse and conveyance are in readiness all the time for the benefit of the guests and family. The house is painted buff and has a commodious porch all around its front and side. The awning and vines that clamber about it render it a delightful retreat. On the left side is a handsome shed, under which the carriage is driven and which lets the occupants on to the steps of the portico. The house is arranged very conveniently. The parlor is in the center front and opens at either end into the hall and dining-room respectively. The parlor is furnished in blue, a light blue paper on the walls and a darker shade of blue used in the upholstery of the furniture. Many rugs are placed over the hardwood floor. The hall has a bow window that is fitted out with a window seat, upholstered in corduroy cushions. There are bathrooms with hot and cold water that is supplied by the reservoirs that are placed on top of the house. Fine stock, fruit and a garden are among the attractions of the place, not to mention the hospitable hostess, Mrs. Miller, and her charming |

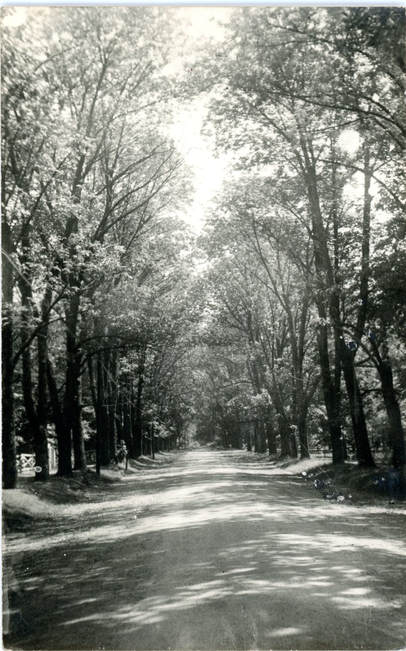

Kate Matthews photo postcard of Pewee Valley's Ashwood (now Ash) Avenue

Kate Matthews photo postcard of Pewee Valley's Ashwood (now Ash) Avenue

daughter, Eleanor Miller. There is usually a large number of friends and relatives being constantly entertained by the family ...

In 1892, when the Millers purchased the Truman property, Pewee's reputation as a summer community was growing. Five years later, on July 11, 1897, the Courier-Journal ran a story by Harry Hurst called, "Some of the Pretty Houses of Pewee," that focused on the rivalry between Pewee Valley and Anchorage for summer visitors. Among the homes featured was the Miller place:

All the stations on the Short Line are more or less entitled to be called summer resorts; but Pewee Valley and Anchorage have long enjoyed a dual preeminence which has necessarily invited comparisons and at last resulted in a spirited, but good-natured rivalry.

Very different conditions exist in the two towns. Anchorage has a wealthy class of Louisville business men, who have selected it as their home, and have spent money freely in improving and beautifying the little suburb. This class in Pewee Valley is much smaller. But the Oldham county town perhaps leads its rival in the number of well-to-do citizens, who occupy handsome residences in its confines during the summer. These man are not one whit behind their wealthy neighbors of Anchorage in improving their personal property, but they have naturally hesitated to invest in improvements which could not benefit the town during the winter. The streets of Anchorage are of macadam, and excellent both winter and summer. In the latter season they are equaled by the Peweean thoroughfares, but after the first of December freeze -- and its subsequent thaw -- there is another story. However, it is simple justice to say that Pewee is improving in this respect, and from present indications the time is near when she will be fully abreast of her rival.

As a summer resort, Pewee has a very evident advantage in the possession of the Villa Ridge Inn. During the winter this building is used as a school, but about June 1 its doors are thrown open to summer patrons. At this season the Kentucky College is also converted into a hotel. Only two private families make a business of taking in summer boarders.

In its pleasing aspect, the varied beauty of its surrounding territory, and the excellence of its society, Pewee effects great inducements to those summer wanderers ambitious of something more than fresh air and good water.

The town is laid out in wide avenues, each of which is planted on both sides with a shade variety of trees, and bears the name of that tree. The houses are set far back and the roomy lawns are clean and well-kept ... The turnpikes which radiate from Pewee afford opportunities to the devotees of Nature to court her in all her moods. The Black Bridge and the Old Mill have long been altars of Pewee's sentimentalists. Fine farms and growing crops can be seen in almost any direction. Everywhere are the Pewee grapes famous in Chicago and the markets of the Northwest. Floyds Fork, besides the scenery, offers fair sport to the wielder of rod and reel.

If the newcomer be socially inclined he will find much to interest him in Pewee society. Most of the town's best families have grown up with the place. There is an atmosphere of antiquity, of tradition, which is in captivating harmony with the massive trees that decorate the lawns and line the broad avenues. And that conservatism which one so rarely finds in new and mixed societies is as firmly planted as the Pewee oaks and ashes. Pewee is not an aristocracy of wealth, though most of its members are in easy circumstances. Many of them have retired from business on a moderate fortune.

To see Pewee at its best is to see it in midsummer from the window of the 5:25 train from the city. This train brings most of the town's transient male population from their labors in the dusty metropolis. Pewee turns out en masse to meet them. Side by side are the staid, respectable rockaway of the native Peweeans and the dashing turnout of the rich summer citizen. There is a sprinkling of horsemen and horsewomen, as well as bicyclists of both sexes. Ponies, dog carts and children add to the pleasure. The broad station platform is aglow with color and action ...

The Source of the Miller Fortune

From Harry Hurst's perspective, Samuel and Henrietta Miller counted among the town's "rich summer citizens." By the time he purchased his Pewee retreat, Samuel was 53 and had made a fortune manufacturing gas and water line pipe for towns across Kentucky and the Midwest. This biography of his life and career appeared the year after he died in "Memorial History of Louisville from Its First Settlement to the Year 1896, Volume 1" by Josiah Stoddard Johnston (American Biographical Publishing Company, Louisville, Ky.; 1896):

Portrait of Samuel Adams Miller

Portrait of Samuel Adams Miller

SAMUEL ADAMS MILLER, manufacturer, and for many years prior to his death one of the foremost business men of Louisville, was born in this city February 19, 1839, and died in Asheville, North Carolina, February 2, 1895. His father died when the son was very young, and he was brought up under the care and guardianship of his mother, a lady of high character and superior intellectual endowments, who, before her marriage, was Miss Baxter, sister of John G. Baxter, prominent as a merchant and several times mayor of Louisville. His education was obtained in the city schools, and although he found it necessary to become self-supporting when he was fifteen years of age, he entered upon the active business of life with a good practical knowledge of all the English branches and with a foundation well laid for broader attainments.

His first experience in business was in the mercantile line, and for some time he was a clerk in Frank Madden's store on Third Street. Later he entered the employ of John G. Baxter, and under the preceptorship of this able and accomplished business man received the thorough training which fitted him for a busy and successful life. Capable, efficient and apt in the discharge of his duties, and courteous in his intercourse with those with whom he was brought into contact, he made many friends as a boy and young man among the business men of Louisville, to whom he commended himself by his ready tact, his superior ability and strict integrity. For some time he was clerk of the General Council of the city, and wherever he found employment he carefully husbanded his resources in anticipation of the time when he should be able to engage in business on his own account. He married Miss Mary Henrietta Long—-daughter of that honored citizen of Louisville and noted manufacturer, Dennis Long -—and received from his father-in-law—-himself a self-made man—encouragement and assistance, which was of great value to him in the early years of his business career.

SAMUEL ADAMS MILLER, manufacturer, and for many years prior to his death one of the foremost business men of Louisville, was born in this city February 19, 1839, and died in Asheville, North Carolina, February 2, 1895. His father died when the son was very young, and he was brought up under the care and guardianship of his mother, a lady of high character and superior intellectual endowments, who, before her marriage, was Miss Baxter, sister of John G. Baxter, prominent as a merchant and several times mayor of Louisville. His education was obtained in the city schools, and although he found it necessary to become self-supporting when he was fifteen years of age, he entered upon the active business of life with a good practical knowledge of all the English branches and with a foundation well laid for broader attainments.

His first experience in business was in the mercantile line, and for some time he was a clerk in Frank Madden's store on Third Street. Later he entered the employ of John G. Baxter, and under the preceptorship of this able and accomplished business man received the thorough training which fitted him for a busy and successful life. Capable, efficient and apt in the discharge of his duties, and courteous in his intercourse with those with whom he was brought into contact, he made many friends as a boy and young man among the business men of Louisville, to whom he commended himself by his ready tact, his superior ability and strict integrity. For some time he was clerk of the General Council of the city, and wherever he found employment he carefully husbanded his resources in anticipation of the time when he should be able to engage in business on his own account. He married Miss Mary Henrietta Long—-daughter of that honored citizen of Louisville and noted manufacturer, Dennis Long -—and received from his father-in-law—-himself a self-made man—encouragement and assistance, which was of great value to him in the early years of his business career.

His experience as a manufacturer began during the Civil War, when he operated what was known as the Broadway Flouring Mill, occupying the site on which the Union Railway Station has since been built. This mill burned down in 1866, and for some time thereafter his time was largely taken up with the work of the Southern Relief Commission, which had been organized by the liberal and philanthropic people of the North to aid those who were suffering from the effects of war and famine in certain portions of the South. Louisville had become a distributing point for the supplies collected from all portions of the country, and the day after his mill burned down Mr. Miller was waited on by a delegation of citizens who requested him to assume general charge of the important work of distributing these supplies to needy sufferers. He accepted the trust and rendered services which entitle him to the lasting gratitude of thousands of people who were recipients of the bounty of a generous people, wisely distributed through his agency.

When he resumed active business he became general manager of the foundry and machine shops of Dennis Long & Company, and it was not long before his genius made itself manifest in the expanding business of that prosperous manufacturing establishment. The company was at that time engaged largely in the manufacture of engines, boilers and other machinery for boats, and pumping engines for water works, and Mr. Miller soon discovered that the making of gas and water pipe would add a line to their manufactures that would vastly extend their business. This speedily became the most remunerative feature of the business and greatly increased prosperity followed. It was not long before Mr. Miller became a partner in the business, and from that time to the end of his life his career was a remarkably active one, rewarded by the accumulation of a large fortune and a position among the most accomplished business men of the South. When the venerable founder of the firm of Dennis Long & Company, desiring to make provision for the perpetuation of the splendid manufacturing plant which had grown up under his management, proposed the organization of a stock company to succeed the partnership then in existence. the sagacious counsel and advice of Mr. Miller contributed largely to the formation of a strong corporation, perfectly adapted to carrying out the designs of Mr. Long and to protect fully the interests of all the stockholders. Of this corporation he became vice-president, and succeeded to the presidency when the esteemed founder of this flourishing industry passed away in 1894.

His fortune grew rapidly and his surplus means were invested from time to time, to a considerable extent, in corporate enterprises in Louisville and other cities, and in this way he came to be a stockholder in many companies and officially connected with a large number of them. The firm of Dennis Long & Company being extensively engaged in the construction of pumping engines and water works supplies Mr. Miller was thus brought into frequent contact with the promoters and builders of city water works. As a result he became quite largely interested in these enterprises, and at the time of his death was president of the Danville Water Company of Danville, Illinois; president of the Owensboro Water Company of Owensboro, Kentucky, and a director of the Frankfort Water Company, of which he also had been president.

He was identified with another of the large manufactories of Louisville as a stockholder and official, being vice-president of the famous plow manufacturing company of B. F. Avery & Sons. He had been director also in the Citizens’ National Bank and in the Columbia Finance & Trust Company, until failing health compelled him to lay aside a portion of his burdens.

His fortune grew rapidly and his surplus means were invested from time to time, to a considerable extent, in corporate enterprises in Louisville and other cities, and in this way he came to be a stockholder in many companies and officially connected with a large number of them. The firm of Dennis Long & Company being extensively engaged in the construction of pumping engines and water works supplies Mr. Miller was thus brought into frequent contact with the promoters and builders of city water works. As a result he became quite largely interested in these enterprises, and at the time of his death was president of the Danville Water Company of Danville, Illinois; president of the Owensboro Water Company of Owensboro, Kentucky, and a director of the Frankfort Water Company, of which he also had been president.

He was identified with another of the large manufactories of Louisville as a stockholder and official, being vice-president of the famous plow manufacturing company of B. F. Avery & Sons. He had been director also in the Citizens’ National Bank and in the Columbia Finance & Trust Company, until failing health compelled him to lay aside a portion of his burdens.

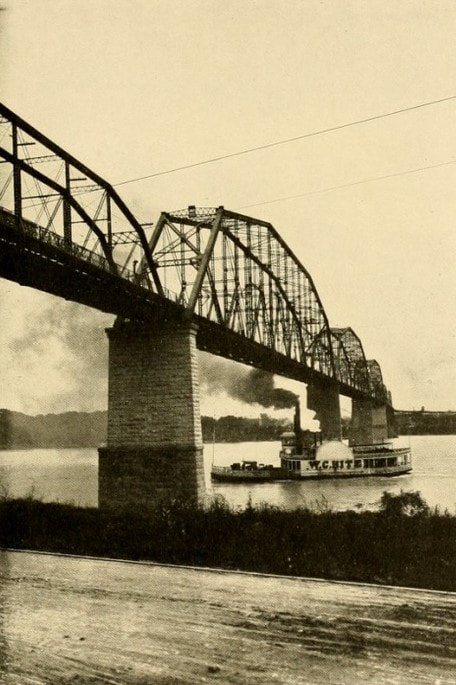

The Jeffersonville Bridge -- a.k.a The Big Four Bridge, which Samuel Miller helped make a reality.The bridge was completed in 1895. Photo from "Baird's History of Clark County, Indiana," published in 1909.

The Jeffersonville Bridge -- a.k.a The Big Four Bridge, which Samuel Miller helped make a reality.The bridge was completed in 1895. Photo from "Baird's History of Clark County, Indiana," published in 1909.

A great work, which stands as a monument to his public spirit, tenacity of purpose and fertility of resources, is the Jeffersonville bridge (Editor's note: known as The Big Four Bridge today) , in the building of which—without disparagement to others—he may be said to have been a leading spirit. Associated with him in the great work of development inaugurated and carried out by the East End Improvement Company were Dennis Long, George J. Long, Joseph Huffaker, Judge James S. Pirtle and others, who ably seconded his efforts, but Mr. Miller was most active in planning the improvement, formulating the financial policy of the corporation and providing necessary resources. A man of great energy, activity and force of character, his perceptions were wonderfully quick and he had a broad grasp of the scope and bearing of the many important business propositions which he was called upon to consider. He was a keen analyst of business situations and frequently astonished his contemporaries and business associates with his easy solutions of perplexing and intricate financial problems. With many and varied interests demanding his attention he applied himself closely to his business pursuits and unconsciously overtasked his strength. Breaking down finally under the strain, a long illness followed, and culminated, as already stated, in his death at Asheville in the early part of 1895.

Until borne down by the cares of business and depressed by illness he was of a peculiarly genial and sunny temperament, and his business associates cherish pleasant memories of his wit and humor and the numerous anecdotes with which he was in the habit of brightening and enlivening his conversation. He made warm and lasting friendships, both in business and social circles, and few men have left a more pleasing impress upon the minds of those with whom they came in contact. A lover of music, literature and the drama, he was a liberal patron of art in all its forms, adorned his own home with paintings and statuary, and belonged to the comparatively limited number of active business men who seem to be as much at home in an art gallery as a counting room. He was especially fond of Napoleonic literature, and collected and read carefully all the English publications relating to the career of the great French soldier and general.

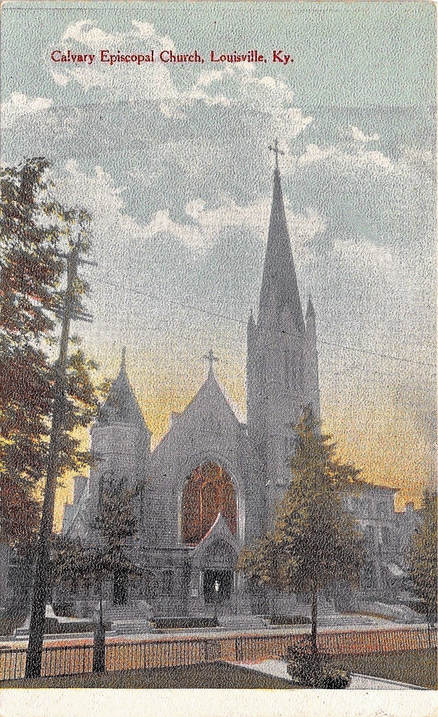

An Episcopalian churchman, he was for many years superintendent of the Sunday School of St. John’s Church, and long a vestryman and warden of that church. Later, on account of a change of residence, he became a member of St. Paul's Church, of which he was also a vestryman. His interest in politics was never active, but his first vote was cast for Abraham Lincoln for President of the United States, and to the end of his life he voted with the Republican party. The surviving members of his family are Mrs. Miller, three daughters and one son. Two of the daughters are married, one being now Mrs. F. W. Koehler, and the other Mrs. A. F. Callahan; and the other two children are Miss Eleanor Everhart Miller and Dennis Long Miller.

Until borne down by the cares of business and depressed by illness he was of a peculiarly genial and sunny temperament, and his business associates cherish pleasant memories of his wit and humor and the numerous anecdotes with which he was in the habit of brightening and enlivening his conversation. He made warm and lasting friendships, both in business and social circles, and few men have left a more pleasing impress upon the minds of those with whom they came in contact. A lover of music, literature and the drama, he was a liberal patron of art in all its forms, adorned his own home with paintings and statuary, and belonged to the comparatively limited number of active business men who seem to be as much at home in an art gallery as a counting room. He was especially fond of Napoleonic literature, and collected and read carefully all the English publications relating to the career of the great French soldier and general.

An Episcopalian churchman, he was for many years superintendent of the Sunday School of St. John’s Church, and long a vestryman and warden of that church. Later, on account of a change of residence, he became a member of St. Paul's Church, of which he was also a vestryman. His interest in politics was never active, but his first vote was cast for Abraham Lincoln for President of the United States, and to the end of his life he voted with the Republican party. The surviving members of his family are Mrs. Miller, three daughters and one son. Two of the daughters are married, one being now Mrs. F. W. Koehler, and the other Mrs. A. F. Callahan; and the other two children are Miss Eleanor Everhart Miller and Dennis Long Miller.

Samuel Miller's Untimely Death

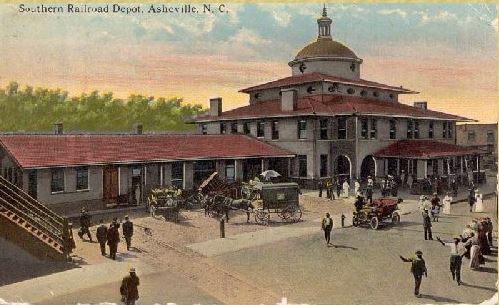

Colorized postcard of the depot at Asheville where Samuel Miller took his own life by jumping in front of a train. One report said he was run over by two cars before the engineer was able to stop.

Colorized postcard of the depot at Asheville where Samuel Miller took his own life by jumping in front of a train. One report said he was run over by two cars before the engineer was able to stop.

Samuel Miller suffered from "acute melancholia" -- known as depression today -- and that disease eventually led him to take his own life. He met his Maker on February 3, 1895, while vacationing in Asheville, N.C. The Asheville Weekly Citizen related the tragic tale on February 5:

MILLIONAIRE MILLER'S DEATH

________________________________

PARTICULARS OF THE FEARFUL

OCCURRENCE

________________________________

Mr. Miller Had Gone to the Station to

Meet His Daughter -- The Son's Pre-

sence of Mind --Remains Take to

Louisville Sunday Afternoon

The suicide (for such it seems undoubtedly to have been) of Samuel A. Miller, the Louisville, Ky., millionaire, was a peculiarly sad occurrence. Mr. Miller came to Asheville about three months ago, suffering from melancholia, and the family took the late Judge E. J. Ason's house on Church St., intending to remain until April 1, in that hope that here, away from the burden of business cares, his health and spirits would be restored.

Sunday afternoon, Mr. Miller, accompanied by his son, Dennis Long Miller, and little grandson, went to the station one of his daughters (editor's note: this was his unmarried daughter, Eleanor, nicknamed "Babes"), who came in on the 2:13 train. The three stood together at the shed, the boy, who is seven or eight years old, holding his grandfather's hand.

As the train steamed into the station Mr. Miller stepped behind his son and suddenly several bystanders were horrified to see him plunge under a baggage car. He still held the grandson's hand and the little fellow himself had a narrow escape from death. As the father made his spring to death the son grasped him and would have been thrown under the wheels, but for the car steps, which knocked him back.

Mr. Miller was dragged a short distance before the train stopped. Among those who stood near was Dr. Chas. S. Jordan, and he ran to where Mr. Miller lay. He found that death had come instantaneously. One of Mr. Miller's arms was crushed off, and the other almost so, while the wheels had passed over his chest. There were few bruises on the face.

The presence of mind shown by the son under agonizing circumstances was wonderful. Turning to a gentleman in the crowd he asked, "Will you take care of this little boy for a few minutes?" He then ran down to the car where his sister was just getting off. She, seeing the mud on his clothes, asked him what was the matter, and the son, without betraying the terrible news, answered that there had been an accident. He escorted his sister to a carriage, returned and took the boy to the carriage and sent them home. It was not until he returned to the side of his father that the young man broke down under the strain.

Mr. Miller was about 55 years old. Concerning him Dr. T.E. Linn said to THE CITIZEN today: "Mr. Miller was one of the most prominent men of Louisville. He was president of the Dennis Long & Co. pipes and casting foundry; president of the Danville, Ill., water works; president of the Owensboro, Ky., water works; director of the Bank of Kentucky; vice-president of the B.F. Avery plow factory, and president of the East End Improvement company, which constructed the bridge over the Ohio that fell during its construction, resulting in the death of a large number of employees. It was this accident that had much to do with Mr. Miller's condition prior to his death. Mr. Miller came to Asheville in search of health and rest, as he was suffering with acute melancholia, and had been under my professional care for that affliction."

A wife and four children, three daughters and one son, survive Mr. Miller.

His son-in-law Mr. Callahan came here from Louisville yesterday and returned on the 3:56 train, which conveyed the remains and the stricken family to Louisville. The pallbearers were John Child, F. Stikeleather, Alex. Webb, H.A. Miller, W.T. Penniman and T.L. Tincher. The interment occurred at Louisville this afternoon.

The suicide also received extensive coverage in both the Nashville Tennessean and Cincinnati Enquirer. The February 3, 1895 Enquirer noted:

.... Mr. Miller left Louisville about a month ago, after a long siege with melancholia and insomnia. He appeared at the clubs to be under some fearful nervous strain, and seemed slowly wearing away. He was very much discouraged at his inability to find relief, and finally went to Asheville as a last resort. His letters had been decidedly cheerful of late, and so gratified was the family in the apparent change that preparations were making to take up permanent residence at Asheville. He requested his daughter to join him, and her arrival is what took him to the depot, where he was killed ...

The Tennessean attributed his depression to health issues. Their story about Samuel Miller's death on February 3 stated:

... Mr. Miller about eight months ago learned he was afflicted by lung trouble and since then attacks of melancholy had proved to be very frequent with him. As he had spells of despondency, his family kept a watch on him.

About six months ago he went to Colorado and there consulted a Philadelphia specialist. He was advised to go to Asheville ...

.... Mr. Miller left Louisville about a month ago, after a long siege with melancholia and insomnia. He appeared at the clubs to be under some fearful nervous strain, and seemed slowly wearing away. He was very much discouraged at his inability to find relief, and finally went to Asheville as a last resort. His letters had been decidedly cheerful of late, and so gratified was the family in the apparent change that preparations were making to take up permanent residence at Asheville. He requested his daughter to join him, and her arrival is what took him to the depot, where he was killed ...

The Tennessean attributed his depression to health issues. Their story about Samuel Miller's death on February 3 stated:

... Mr. Miller about eight months ago learned he was afflicted by lung trouble and since then attacks of melancholy had proved to be very frequent with him. As he had spells of despondency, his family kept a watch on him.

About six months ago he went to Colorado and there consulted a Philadelphia specialist. He was advised to go to Asheville ...

|

Whether his depression was caused by lung trouble or unassuageable guilt over the many deaths that occurred during the construction of The Big Four Bridge may never be known. But one thing is certain. The bridge project was beset with fatalities from the beginning, and 37 men died during its construction. The first fatalities occurred when twelve men working on a pier foundation drowned after a caisson failed to hold back the river. A second, similar accident took another four lives. But by far and away the greatest loss of life occurred on December 15, 1893 when the structure collapsed in high winds and plunged forty men into the Ohio River's icy waters. Twenty-one of them died. The next day's Courier-Journal devoted two full pages to the tragedy:

DEATH UNDID THE BUILDING ______________________________________ Another Appalling Accident Added to An Already Long List of Horrors __________________________________________ Two Spans, Weakened By the Wind, Fall From the Jeffersonville Bridge. ___________________________________________ The First Drops in the Morning, Carrying Down With It Over Two-Score Victims. ________________________________________ A Few Miraculously Escape and Some Still Sur- vive Their Terrible Injuries. ____________________________________________ The Second Span Crashes Down During a Stiff Gust Early Last Evening. ____________________________________________ No One On the Structure At the Time, But the Financial Loss Will Be Much Heavier. ____________________________________________ Bridge Officials Deny That There Was Anything Faulty in the Work, But Others Dubious. ____________________________________________ |

Photos of the Big Four Bridge Collapse in December 1893

|

THE GREAT LOSS BOTH TO LIFE AND PROPERTY.

The ill-fated Jeffersonville bridge has again been checked in its building by another terrible loss of life and property. Two spans fell yesterday, one in the morning and the other last evening.

The first disaster carried down about fifty men, of whom only a few escaped death or injury. No one was hurt in the second accident, but the financial loss was greater...

... The high winds that prevailed all Thursday night and yesterday are alleged by the bridge builders to have been the cause of the disaster, though the faulty and hasty construction of the false-work may have made the wrecking by the gusts much easier. Plenty of workmen charge this.

It was about 10:20 o’clock in the morning when the first accident happened. The large span was almost completed, and the lower part of it hung eighty-six feet from the water. On top of the bridge was a “traveler,” a huge frame affair, 104 1-2 feet high, eighty feet long and about twenty feet wide. The “traveler” in itself was top-heavy and ran on a track built for it on top of the false-work.

In the strong wind, this huge mass of timber swayed backward and forward, each vibration materially weakening the frame false-work below. A harder gust and another vibration gave the timbers the last strain. The false-work began to sink, and the “traveler” toppled sidewise. It carried with it into the river the false-work, the almost-completed steel span and forty-eight men at work upon it.

The other span went down under a heavy gale last evening at 5:10 o’clock (might be 8:10), leaving not a particle of it swinging. No one was on the span or under it, though a ferryboat had passed beneath it but a few minutes before.

The actual loss to the Phoenix Bridge Company by the wrecking of the two spans is placed at $135,000, not counting the labor employed in placing them in position.

THE ACCIDENT

Condition of the Work Before the Toppling of the Traveler

Danger Warnings Unheeded.

Those who saw the giving way of the span were so horrified that few of them could give a good description of the disaster. When the men went to work yesterday, they found the wind blowing at the rate of about twenty miles an hour. As they climbed to their places in the false-work, they were more careful than usual, for under the strain of the wind the huge “traveler” was perceptibly rocking, and its swaying motion was plainly felt by all who were at work upon it or on the nearly completed span or the false-work on which it rested.

The span was nearly completed, and nearly all the iron work was in position. The “traveler” was at the extreme northern end of the span ... About 175 feet of the iron work of the span was already in position, and the remainder was rapidly being put up. The “traveler” was a tall, frame structure, 104 1-2 feet high, 80 feet long and about 20 foot wide. It ran on a track built for it, and was constructed so that it could be moved along as the work progressed. There were four or five engines on the “traveler,” used to hoist the heavy iron beams and hold them while they were being put in position. In this “traveler” most of the men were at work, some at the very top, 190 feet from the water’s edge.

To give a better illustration of how the accident happened it is necessary to describe the work as it stood at the time the accident occurred. In order to erect the span false-work was first placed in position. Piling was driven into the river bed at intervals of about fifteen feet. The piles protruded about ten feet from the surface of the water. From those “bents(?)” were framed 6×10 timbers, making a false-work the length of the span, and the top being eighty-six feet from the water level. This false-work is the same as is erected for any cantilever bridge, and, except in unusual instances, will hold up the span until it is joined, when it is able to hold itself up. Then the false-work is torn away.

When the false-work has been constructed the work of erecting the span is begun. The heavy steel girder are hoisted into position by the “traveler” and held until bolted to others previously erected. As girder after girder is erected, the “traveler” is moved ahead on the track built on the false-work, until the opposite pier is reached. The work is begun on the next span in the same manner.

At the time of the accident the traveler was within a few feet of the third pier. The iron work behind it had all been placed in position, and by nightfall it was expected the span would have been swung.

The men at work in mid air, accustomed as they were at their task, were more cautious than ever yesterday, for the wind was very high. In the wind the tall “traveler” swayed gently, weakening in its very motion the false-work on which it rested.

The men above could not see the danger as well as those below. Those at work on the pile-driver below feared trouble, though they made no effort to warn the men in the bridge above. However, the pile-driver was moved from immediately beneath the bridge some little distance upstream, it being feared from the rocking of the “traveler” that it might fall.

The false-work must have been greatly weakened by the rocking of the “traveler” and as it sank slowly the momentum of the powerful “traveler” came greater.

Suddenly there came a cracking sound, as heavy timbers were rent in two. This was the only warning signal received by the men. Then there was a rush for the piers. About twenty-five escaped to the piers, and the rest went with the “traveler,” span and false-work into the river below, but a small number of the forty-eight believed to have fallen escaping.

The crashing of the timbers let the “traveler” down several feet on one side. The next gust of wind toppled it over. As the mass of timbers fell, it carried with it that part of the false-work immediately below the “traveler.” This weakened the rest of the false-work and in less than a minute all had fallen into the river with a fearful crash., the sound of which was heard for squares.

When once the span had commenced to topple there began a struggle for life to which a (unreadable) on a sinking ship could hardly be compared. There was not only the terrible prospect of a watery grave below, but the plunge thereto was even more frightful, the distance being eighty feet.

The fall of the traveler with its load of humanity caused such a splash that few heeded the tumbling of the larger end of the span between that and the Kentucky shore. It went down gradually, resembling, as one witness said, the closing up of a carpenter’s rule, so that the men who made for the next pier toward the Kentucky shore were actually running up hill. Among the number was Frank Brown, who was working at the bottom of the traveler. He thinks that there were fifteen or twenty men in the crowd that escaped with him by rushing toward the Kentucky shore. The poor fellow who was the last of those running lost his life by a second. For fully ten feet he ran up hill, as it were, for the trestle was by that time slanting. Several of his companions turned and saw him attempt to take one more step, which would have landed him safely on the pier, but the last remnant of the span went down with a crash, and he went with it. In the hurry and excitement they did not recognize who he was, but it is certain that when all the missing are accounted for his name will be among them.

All who escaped say they were warned of the coming catastrophe by a quake and a lunge of the heavy beams and front-work. The traveler being within only a few yards of the pier that stands in the middle of the channel, all the men who could possibly do so, or who had the presence of mind, made for this instead of the pier toward the Kentucky side, which was several hundred feet distant. When the wreckage had fallen into the water fifteen men – about as many as it could hold – were soon standing on the top of this stone pier, some of them trembling with excitement and the danger of the situation. It was only a few moments when the frame work which had been built only a few feet on the other side of the pier toward the Indiana side began to crack. It fell with a crash, and one of the guide ropes attached to it caught a man named Kelley around the legs near the knees and jerked him from the top of the pier to the water. He fell on the debris, and was being carried rapidly down stream when a boat manned by Capt. Devas and three life-savers (relieved?) him from the perilous position. A hole was cut deep into his head, another was in his side. The life-savers took him quietly to the shore. He was placed into a patrol wagon and carried to one of the hospitals, where he soon died. The remaining fourteen the slid town a rope into a boat which had come to their rescue. Thus escaped the thirty or forty men known to have been saved, except a few special cases that are deserving of a particular mention.

THE WORK OF RESCUE.

Incidents of Heroism and Narrow Escape That Occurred Just After the Falling of the Pier.

In the whirlpool and seething waters caused by the falloff the immense structure there was little more chance for a man to save himself than there is for a drowning man to escape by grasping a straw. Those who from fright clung to the timbers went down with the bridge never to rise again except in death. They are buried where no helping hand could reach them, and it is not theorizing to say that they gave up their lives without even so much as a struggle. But a number leaped as the span fell, so that they were carried high up on the works, dropped on the debris, fatally injured, or with legs, arms or ribs broken, there to be rescued by the scores of brave men who paddled to the rescue. It required a stout boat to venture into the midst of this scene with a frail skiff. The wind still blew upstream at a terrific rate, chopping the waves into great lumps of water that beat against a resisting object with almost irresistible force.

It was not less than a half an hour before this welling and heaving of the water consequent(?) upon the fall of the iron mass had entirely subsided. Before the timbers and beams had struck the water there went up a cry of distress that even the winds did not drown from the ears of those who chanced to be not far distant. Private Watchman Collins was un a skiff a few yards below the bridge, and not far from the Hotspur. The crackling of the timbers reached his ears and he raised his eyes in time to see the great span come toppling down. His skiff was caught in the whirlpool. Like a straw it was capsized and he was struggling with the waves. By the merest good luck his hand struck the skiff, and he not only saved his own life, but, wet to the skin, went to work with a will, trying to help others in distress. “I could hear their cries for help,” he said, “long before they struck the water. The scene reminded me of pictures I have seen of men with arms outstretched and in every conceivable position leaping from the windows of a burning building. It is impressed upon my mind like a photograph, and the details are clear to me, I could see many of them clinging to the span – hugging it as if it was their only salvation. But a poor one it turned out to be, for they were crushed to the bottom of the river, where I believe some are so deep in the mud that they will never have another grave.”

This first person to the rescue and who saved the first man was Martin Donahue, a young man of about twenty-two years, who was sitting in a skiff near the bank just below the bridge. As soon as the span began to sway he pulled toward it. Reaching the third pier he saw the man fall who only needed one more step to save himself. Being a good oarsman he reached the scene in time to be tossed high upon the waves. On the cap of one of those he caught George Brown, whose arm was broken. Dragging him into the boat he made for the shore, where he soon landed with the injured man and returned to the rescue.

The Lifesavers had arrived by this time. Men on the wharfboat shouted to them that the bridge had fallen. Capt. Devan ordered out two lifesaving boats with a crew of three men in each. They made the pull of their lives, and with the assistance of the gale went up stream like an arrow. First one then the other forged ahead, the race of the two splendid crews exciting the admiration erven of the excited people on shore. The distance of a (unreadable) is made in a remarkably short time, but, not even wearied of the pull, they were ready for hard work. Kelly’s life was (unreadable) to their good work, for the drift on which he lay dying was whirled a quarter of a mile down stream, where it was caught on a heavy snag of sandbar. The Hotspur being already on the scene, gave valuable assistance.

Those people below saw a brave act on the part of a man who proved to be one Gilder. He and ... Hawks were working side by side. The shuck came and, simultaneously, they dropped their tools. Gilder was the foremost of the two. With yet a stretch of a hundred feet between them and the next pier in the direction of the Kentucky side, Gilder heard a cry. A quick turn of the head showed that his companion, Hawks, had stopped. His foot was caught in the trestlework. The bridge was giving way almost as fast as they sped over it toward safety. Gibber did not give thought to danger but, turning quickly, he went to the assistance of his friend as quickly as he was fleeing from death. Hawks’ foot was released, and, almost as the timbers fell beneath their feet, they escaped the pier.

All these things occupied but a short while. The afternoon was spent in clearing away the debris. It will be several days before this is completed. The lifting of the great bent pieces of iron, which are riveted together, will be the hardest part.

The wreckage leaves a line of debris extending high above water from the two large piers on which the span rested. The derrick was brought into use and seventy bridge-builders who were off duty at the time of the accident were set to work. The machinery was lifted from the river first, and to do this it took all the afternoon. There was great danger in this work. The men were paid twenty-five cents an hour. They slipped about on the broken timbers in the water as if they were on dry land, and apparently forgetful or unmindful of the tragedy that had just occurred, except that each and every one of them kept a sharp lookout for any evidence of the presence of corpses.

AT THE HOSPITAL

Two of the Wounded Die Soon After Being Received

Addresses of the Others.

In the southwest ward of the City Hospital a row of cots was filled early in the afternoon with maimed, gashed and bruised survivors of the accident. Dr. W.L. Rodman, the bridge surgeon, who is assisted by Dr. George W. Griffiths, J.M. Williams and R. M. Jones, ordered most of them to be removed to the central ward, but before the removal was completed two of the sufferers had died...

... The Farmers’ Home, on Market street, near Preston, was the temporary home of many of the men employed on the bridge works, and of these two were brought to their own rooms more or less injured. They were D.F. Hall, arm and hip fractured, and George E. Shehan, Greenup, Ky., flesh torn from right side. These also received the attention of Dr. Rodman.

It was not easy to get a clear or connected account of their individual experiences from the suffering men. Most of them were either half unconscious or too weak to be troubled with questions. G.W. Brown could talk freely and said that he had plenty of warning to enable him to escape if he had been willing to go back to the Jeffersonville side, but he delayed too long and then tried to run to the Louisville pier. When he was about 100 feet from this pier, the bridge gave way under him. He was struck by some of the falling pieces, but, being a strong swimmer, managed, in spite of his broken arm, to get to the surface when he was rescued by a boat.

Ed Hoban, of Chicago, has excited the admiration of Dr. Rodman and the hospital staff more perhaps than any other of the emergency patients by his pluck. Lying on his back on his cot with a broken leg, and unable to sleep because he could not turn on his side, Hoban told a reporter that there had been plenty of time to get off the roadway of the bridge, where he was, if it had not been that they wanted to move the traveler back. When matters became desperate, Hoban ran for the Louisville pier with the rest, but he had waited too long. He, with Hinekley(?), who was killed, fell and caught the bottom cord, but that was falling, too, so Hoban let go of it when it touched the water, fearing to be jammed under it at the bottom of the river. Timbers were shooting up, he said, on every side, and some of these struck him: still he struck out for the surface and held on until the Hotspur came and picked him up.

G.E. Sheehan, at the Farmer’s Home, was lying in bed apparently in fair spirits by 3 o’clock. His torn side troubled him, but he was sufficiently recovered from the shock to ask for a chaw of tobacco. This is Sheehan’s second experience in bridge accidents on the Ohio river. A year ago last summer he was in a similar accident in Covington and that time escaped without any damage. He described his fall and his struggle under water to get to “where he thought was the top.” The fragments were in his way, but he struggled on toward the light and got to it. While holding on to a piece of the bridge he was hailed by a man in a boat and asked to come and help pull out another man, but it was all he could do to keep himself safe.

Late last night the injured men at the City Hospital were resting easily. Dr. Rodman, the bridge company’s surgeon, said last night the worst hurt of any of the men was Hildebrand and Hoben. The doctor said their death or recovery depended upon the extent of internal injuries they had received, and that that could not be determined for some hours. Both cases, he said, were critical, but not hopeless. The doctor said he thought it would be necessary to amputate the shattered leg of young Meyers in order to save his life. Meyers would not consent to it yesterday, and would not even let the doctors talk of such a thing. G. W. Brown, whose left arm was broken in two places, was sound asleep when his mother, who had heard the news and had come from her home in Irvington, called to see him.

HARRY LEE’S THRILLING EXPERIENCE.

Dived from the Top of the Traveler and Though Seriously Injured Escapes Alive.

By far the most thrilling experience, and one which required the display of the most remarkable nerve, was that of Harry Lee, of New Albany. He is known as one of the most daring of the bridge builders and the manager gave him work that many others would not have attempted.

When the warning of disaster came it found him perched on the topmost point of the traveler, 190 feet from the water. With him was a man whose first name was Fred. He was from Lincoln, Ill. The other men on the traveler were far below them. Lee’s companion seized the iron rigging, in which they were climbing like sailors. He clung on for dear life, and when the span went down, he went with it to his grave, for he was probably buried in the mud at the bottom of the river. Lee is a slender but hardy young man of twenty-five years. He knew it was certain death to stick to the “traveler,” so he resolved to take a desperate chance. At the first signal of danger, he clambered to the very top, only a foot or so above where he already stood. Then he raised himself at full height. The great span trembled beneath him. Still he stood there immovable, and two eye witnesses who were at a safe distance in the river below held their breath in the expectation of what was to follow. Once or twice the strong wind swayed the structure, until its momentum was sufficient to topple it over.

Then Lee made ready. The wind had already tossed his hat far upstream. Even at that height he had the presence of mind to station himself on the lower side, knowing that the wind would blow the wreckage upstream. He was seen by those blow to place his hands above his head in the shape of a V, his form clearly outlined against the sky. Then stooping, he made a plunge head first from the height. Like an arrow he shot toward the river, never turning once in his course, nor removing his hands from before his head. Though it must have been hardly as many seconds, it seemed fully like five minutes before Lee struck the water. Watchman Collins and Martin Donahue, the boy who rescued George Brown, saw him disappear. Coming arrowlike from that height of 100 feet they never expected to see him again. But the result of the leap was worth the chance, for Lee soon appeared on a big wave, from which he was rescued. His leg was broken, his body was blue from the concussion (?) with the water, but his life was saved, and he bore the record of as daring a leap, probably, as ever a man made.

ON THE JEFFERSONVILLE SIDE.

Scenes Witnessed By People of the Hoosier Suburb

Dead and Injured On That Side.

Five thousand people surged along the river front in Jeffersonville shortly after the catastrophe. The people of the city were attracted by a roaring sound when the collapse came., and all, reminded of the cyclone, which laid waste a portion of the city, were almost paralyzed at the prospect of another visitation of the storm demon. The blowing of whistles on the river and the ringing of steamers’ bells added to the excitement, and almost the whole population ran to the scene from every direction. The crowd stood in amazement, powerless to render assistance to the man, many of whom could be seen struggling to reach a place of safety and then sink to death.

Men in skiffs hastened to the spot. Jerry Bealey(?), who manned one, reached Harry Lee in time to rescue him. His thrilling escape is detailed elsewhere. Lee was taken to the home of Rev. T. Bosley(?), where he is at present being provided for.

Dr. D.C. Peyton, surgeon for the bridge company in Jeffersonville, was pulled to the scene in a skiff by Bud Matthews and Louis Valderbill(?). The small “traveler” on pier No. 5 was still apparently intact, and just as the skiff containing Dr. Peyton and the two oarsmen were passing by it collapsed with a crash carrying with it an engine used in hoisting bridge iron into position. The shouts of these on the shore and the danger in which the boatmen found themselves caused them to become excited and in consequence their craft was overturned. Dr. Peyton pitched headlong into the river and arose under a pile of debris. Those on the river bank waited in suspense for him to appear, which he did an instant later. He had been carried several feet by the undercurrent, however, and sank twice before assistance reached him. Two young men in a skiff saved him just in time. Herman Rave(?), the newspaper man, also had a close call, falling from a skiff, but being an adept swimmer reached the boat unassisted.

When the span began to quiver and the “traveler” plunged into the river, among those who reached pier No. 5 in safety was Frank Simmons, of Jeffersonville. It was at the moment the small “traveler” gave way and fell. A rope, and some manner, became entangled about the body of Simmons, and before he could extricate himself he was pulled from his position. He turned over and over in descending, and struck some timbers near the pier. His death must have been instantaneous for he never appeared on the surface. His body was not recovered. He leaves a wife, who resides on Mulberry street in Jeffersonville. Simmons formerly lived in Phoenixville, Pa., and had been in the employ of the Phoenix Bridge Company for several years. The ferry Steamer City of Jeffersonville picked up the dead body of Frank D. Burns and conveyed it to the Spring street dock, whence it was removed to the undertaking establishment of Bamber(?) & Ogden, on East Chestnut street. Coroner Gilbert viewed the remains and heard the evidence of several witnesses. He returned a verdict in accordance with the facts. William B. Burns identified the body as that of his brother. The home of the dead man was in Franklin, Pa., where the body will be shipped this morning. The surviving brother is also employed on the bridge, but had been ill for two days and was not at work yesterday.

Two men were taken to the City Infirmary, on East Front street. They were Harry Pugh of Mercer county, Pa., and Oliver Moore, whose home is at 101 Altor street, Philadelphia. Pugh had his back and his head injured. Moore’s spine was wrenched and both arms were broken. He is in precarious condition, while that of Pugh is not regarded by the physicians. Drs. Peyton, Walker and Fields, as serious.

A Courier-Journal reporter called to see the men last night. Moore was asleep but Pugh was not. He spoke with some reluctance, saying, “I have been with the Phoenix Bridge Company for several years. I regarded the false work as safe, but there were several of the workmen who did not, and I believe that some of them left on that account. I was under the traveler pulling wires(?), preparatory to its being moved to the center of the span, when I heard it crack, and then I knew what was coming. I think if we had gotten the “traveler” moved the accident would not have happened. I have no idea how many men were killed. Probably eighty men were at work.”

One of the most remarkable escapes was that of John Housenberger(?), better known as “French John,” of Port Huron, Mich. He was on top of the “traveler.” As it went down, “French John” held on, and, when within a few feet of the water, he leaped and did not sustain a single scratch.

Ira Dorsey, collector on the ferry boat City of Jeffersonville, was another eye-witness. He said: “We left the First street dock about 10:10 and were passing under the bridge at about quarter after. I was standing on the upper deck talking to a gentleman about the bridge. While we were looking at the structure it suddenly began to quiver. Then the “traveler” shot down like a flash and then the iron work fell with a roaring sound. It caused such a commotion in the river that the waves rolled high in the air and rocked the ferryboat so that we all thought it would capsize.

“Then the cries of mangled and drowning men broke the awful stillness. Some cried, “For God’s sake save us” Pilot Bart Nixon quickly righted the boat and we pulled alongside the wrecked ‘traveler.’ Just then a corpse arose, and it was picked up and placed on board. It was to be the body of John Burns. I saw others floating on the water, but they were in the last throes of death, and sank before we could rescue them. By this time other steamers and dozens of skiffs were at the scene, and many men were picked up by them.

“One man I am certain lost his life after the accident. He was on the pier, and either fell or jumped off. Three or four times he turned over then his body struck some debris, and part of the ‘traveler.’ I think, from what I could observe, that about fifty or sixty men met death.”

Harry Plais (?) of New Albany, brother-in-law of Fire Chief Merker, is among the missing. He is forty-two years of age, and leaves a wife, but no children. When last seen he was working on the false-work directly beneath the mass of iron that fell from above. Only about three minutes before the crash came, Plaiss had been remarking on the dangers in the life of a bridge-builder, and said that “possibly in a few minutes a block might fall from above that would kill both of us.”

William Wilty, another New Albany workman, saved himself by clinging to a rope that was suspended from the pier.

THE SECOND DISASTER

The Third Span from the Kentucky Shore Falls During the Wind, But No Lives Lost.

The accident of the forenoon was duplicated in all but the loss of life at 8:10 o’clock last evening, when the third span from the Kentucky shore fell into the river with a loud crash. So far as is known no lives were lost by this second catastrophe. The river was blockaded by the debris until transit of boats could be made only through the channel between the two piers nearest the Indiana shore. Neither the ferry nor any of the other large boats would attempt this.

The cause of the second accident, like that of the first, is attributed by the bridge men to the high wind. A sharp gust came at that hour and the enormous (something) span, bolted and partially riveted together as it was, fell from the piers.