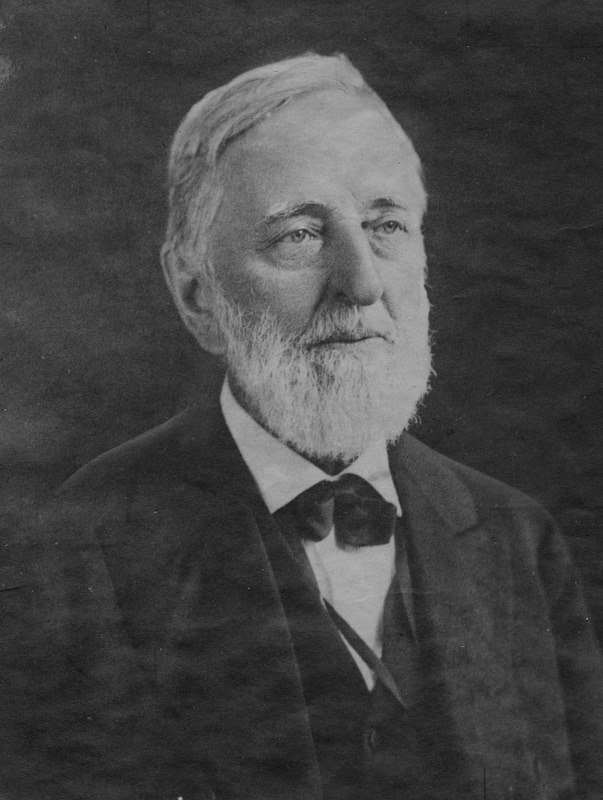

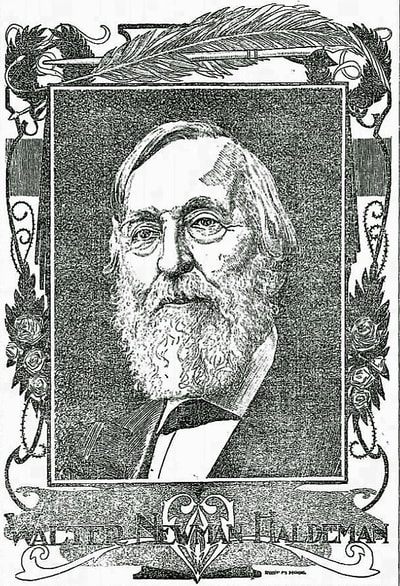

Walter Newman Haldeman (April 27, 1821-May 13, 1902): Founder & Publisher of The Courier-Journal and Louisville Times

|

On October 26, 1895, at the Kentucky Orphan Brigade’s 14th reunion in Bowling Green, Walter Newman Haldeman was elected an honorary member of the brigade association by unanimous vote.

Unlike his oldest son, William Birch, the publisher of The Courier-Journal and Louisville Times didn’t fight for the Confederate cause with rifle or sword. Instead, he fought with his pen and in so doing, lost his Pewee Valley home and his business. Haldeman was born in Maysville, Ky. on April 27, 1821 and attended school at the Maysville Academy. He was 16 when his family moved to Louisville. Three years later, he got his start in newspaper publishing when he took a job working for George Washington Weissinger in the counting room of the Louisville Journal, a newspaper famed throughout the American West for the savage wit and brilliant satire of its editor, George D. Prentice. Haldeman spent three years learning printing, journalism and the business end of newspaper publishing under Weissinger’s watchful eye. That knowledge would serve him well when, through the settling of a debt, he became the proud owner of a four-page paper called the Daily Dime. Within a few months of publishing his first issue on February 12, 1844, he’d substantially increased its circulation by emphasizing news, rather than politics. On June 1, 1844, he changed its name to the Morning Courier. Later that same year, he changed another name when he made the lovely Elizabeth Metcalfe of Cincinnati his wife.

To get his fledgling daily on firm financial footing, Haldeman took on numerous partners and editors, including two men who would later become his neighbors when he moved his family to a stop on the Louisville & Frankfort railroad line then known as Smith’s Station. The first of these was Edwin Bryant, founder of the Lexington Observer, who gained greater fame as the author of “What I Saw in California.” His travel journal became a bestseller during the California gold rush, when the forty-niners adopted it as their guide to the Eureka State. The second was William D. Gallagher, a poet, journalist and contributor to many publications at various times in his career, including the Cincinnati Gazette. However, the two didn’t see eye-to-eye on the issue of slavery and parted ways when Haldeman bought him out. In the fall of 1854 Haldeman, Elizabeth, and their eight-year-old son, Willie, moved from Louisville to the tiny development later known as Pewee Valley. What motivated the 33-year-old newspaperman to swap the convenience of the city for a quiet backwater some 16 miles east was the pursuit of marital harmony. |

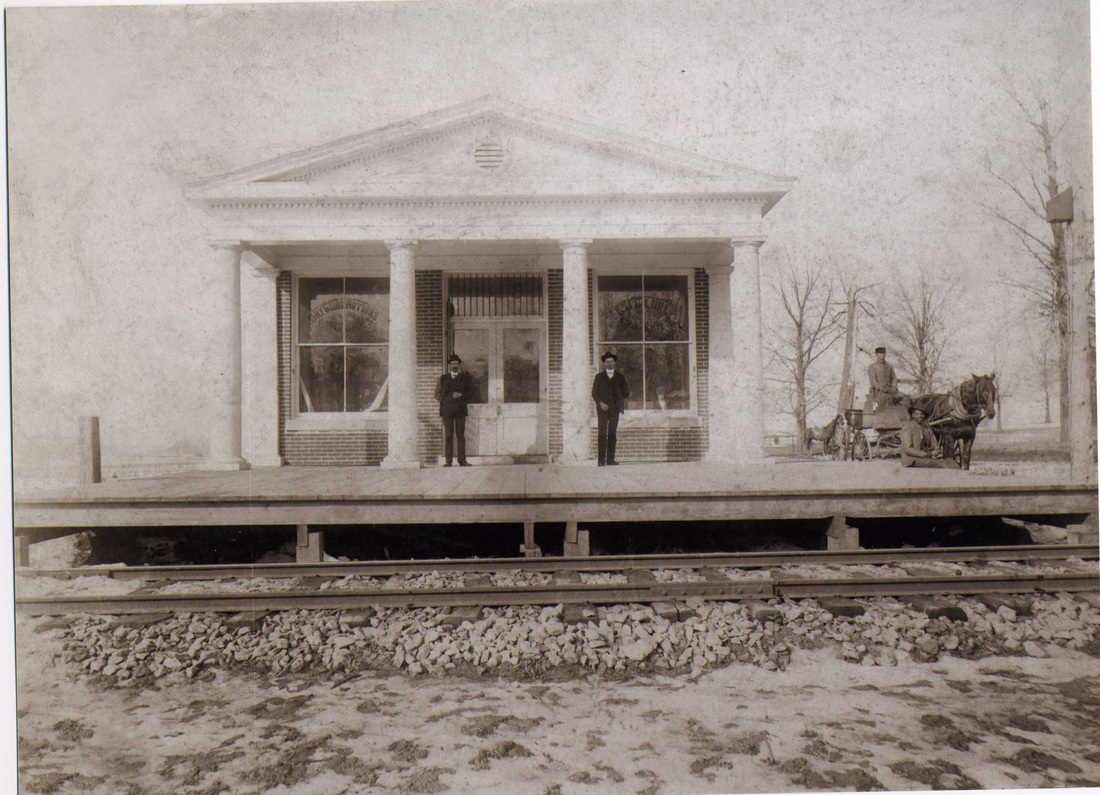

The oldest known photo of Sunnyside, Walter Haldeman's home in Pewee Valley, dates from the Craig era, when the house was renamed Edgewood. The photo appears to date from around 1900.

The oldest known photo of Sunnyside, Walter Haldeman's home in Pewee Valley, dates from the Craig era, when the house was renamed Edgewood. The photo appears to date from around 1900.

Elizabeth fancied herself an invalid and had been neglecting her duties as a wife and mother by spending time away from her family in an attempt to improve her health. In fact, she spent seven months of 1854 – from February to September – at the Cleveland Water Cure. Walter’s purchase of a home in Smith’s Station was an attempt to placate his wife’s fears about Louisville’s unhealthiness.

Since its founding, Louisville’s landscape was dotted with so many ponds, one historian described it as a veritable archipelago. Mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and yellow fever were common, as were outbreaks of typhus and cholera, earning Louisville the dubious nickname, “the Graveyard of the West.”

Located on higher ground away from the banks of the Ohio, Smith’s Station offered a more salubrious environment. The asking price for the spacious, tin-roofed Italianate home set on 50 acres was just $4,000.

Plus, the fledgling town was attracting literary illuminati, including local historian Ben Casseday; journalists Thomas Smith, William Gallagher and Edwin Bryant; textbook author Noble Butler; and novelist Catherine Anne Warfield. William H. Walker, proprietor of Walker’s Exchange, known for serving up gastronomic delights with a side order of politics, owned the property next door. There would be no shortage of scintillating conversation. Haldeman confidently named his country place Sunnyside, purchased new furniture and enticed Elizabeth to come home.

Meanwhile, Haldeman was becoming more political, both in his actions and in his newspaper’s leanings. The Courier supported the election of James Buchanan in 1856 and Haldeman received a reward: a federal patronage post as surveyor of customs for the port of Louisville. The post required that he have signatories for a $50,000 surety bond, since it involved keeping track of public revenues from water traffic on the Ohio River. Signing on his behalf were his then-editor and partner Reuben T. Durrett, his neighbor William Walker, and his brothers-in-law, James Escot and Joseph Metcalfe.

Haldeman spent most of his time on his federal duties, while Durrett ran the paper. That arrangement lasted until 1859, when Durrett decided he wanted to go into the profession he was trained in: law. Durrett hired the fiery Robert McKee of the Maysville Express, a staunch Democrat and advocate of Southern rights, as editor and sold out his interest in the paper.

Both Haldeman and McKee attended the Democratic Party convention in Charleston, Haldeman as a reporter and McKee as Louisville’s delegate. McKee also attended the second convention in Baltimore, when the Charleston convention was able to agree on neither a candidate nor platform. The issue dividing them was slavery. The Courier threw its support to Kentuckian John C. Breckinridge, who went on to be defeated by Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election,

The newspaper’s tone became more strident in the weeks leading up to Lincoln’s inauguration and urged a united South to protect the institution of slavery. The Courier observed, “...Mr. Lincoln will have command of the army and navy, control of the purse and the sword, and will be backed by majorities in both houses of Congress; and already has state after state offered men and arms and money to subjugate the south.”

Haldeman, himself, was no plantation slave owner. Like many Kentuckians, he owned a single slave – an elderly woman named Elva, who was most likely his children’s mammy.

South Carolina was first to secede. By February 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas had followed.

The day after Lincoln’s March 4 inauguration, the Courier made it clear compromise was impossible: “We have heard but one opinion of the inaugural expressed and that opinion is, that it is a declaration of war... The address will be read with care and attention by the people of the border slaveholding states. It will teach them the hopelessness, the folly, the madness of trusting to the honor, to the love of justice or to the patriotism of the people of the Free states … We believe the same end will be reached through peace or war. Reconstruction of the federal union in now impossible. The slave states must and will unite in a common government and the Free states must and will form another confederacy.”

In the aftermath of Ft. Sumter, the public was clamoring for news. The Courier’s circulation shot up by 1200 copies. Haldeman’s competitors relied on associated press reports, which, scoffed the Courier, “all pass through the hands of northern officials and are as full of lies as an egg is of meat.” Instead, Haldeman hired his own war correspondent, Charles D. Kirk or “Se De Kay”, who in a May report from Harper’s Ferry, referred to Union forces as the “enemy.”

Not surprisingly, Haldeman lost his patronage post, but remained in the office until June and did nothing to stop the shipments of munitions and provisions heading south on the L&N. By that time, four more states – Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee – had seceded.

Luckily for Haldeman, Kentucky chose to remain above the fray. Governor McGoffin’s response to Lincoln’s demands for troops made Kentucky’s neutrality clear. “I say, emphatically, that Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister southern states,” he replied to the Secretary of War.

As Dennis Cusick noted in Haldeman’s biography, “Gentleman of the Press,” “Neutrality protected the Courier for a time, allowing it to advocate the Southern cause, cheer the success of the Confederate army and denounce the administration of ‘King Lincoln’…Such a position would have been untenable in the northern states, where newspapers were getting into trouble for much less overt criticism of the government.”

|

The situation changed abruptly on September 19, 1861, when the legislature overrode the governor and authorized the state’s military board to place the commonwealth’s military stores under Union control. The Bluegrass State has officially joined the North.

The Confiscation Act of 1861 authorized Union troops to seize property and slaves used to support the rebel cause. Haldeman and the Courier were immediately targeted by General Robert Anderson, the Union commander then stationed in Louisville. “Within hours of the state legislature’s vote…the United States Post Office department banned the Courier from the mails as an ‘advocate of treason’ and the U.S. marshal seized the Courier’s office and arrested former editor Durrett on a charge of treason. Haldeman was able to avoid arrest only because his residence was in relatively remote Pewee Valley…” Cusick wrote in “Gentleman of the Press.” The next day, while Haldeman waited near Smith’s Station, a party of friends and neighbors, including Noble Butler and William Walker, met with General Anderson at the Louisville Hotel. Haldeman promised them he would mend his ways, abstain from political commentary and allow military censorship of his paper, if he could continue publishing. Financially, he had a lot at stake. He had moved the Courier into new offices and was in debt. There was no reason to believe his desire to keep the presses rolling wasn’t sincere. Anderson approved the deal, but stipulated that Haldeman write an article, subject to the general’s approval, that expressed his regret for the Courier’s past actions and pledged his loyalty to Kentucky and the Union. Haldeman followed through on that promise and the article did, indeed, appear in the September 21st issue of the Louisville Journal. However, that same morning when a messenger arrived at Sunnyside to deliver a letter from the U.S. marshal authorizing the Courier’s reopening, his advocates learned they had been duped. Haldeman had no intention of supporting the Union. Instead, he fled south to Confederate General Simon Bolivar Buckner’s headquarters in Bowling Green, where he was welcomed with open arms. The negotiations had merely bought him time to effect his escape. His supporters were outraged. In the October 9, 1861 edition of the Louisville Journal, his former mentor, George D. Prentice jeered, “Mr. Haldeman holds out…the promise of renewing the publication of the Courier when his friends the confederate troops have conquered Louisville and Kentucky and established the confederate government over us. There is certainly good reason to think he will not come back to raise the Courier from the dead or to do anything else here until the U.S. government shall cease to have any operation among us. Not only have all the printing materials of his late paper been seized by his creditors, but it is found that he, as late surveyor of the customs in Louisville, confiscated at least ten or twelve thousand dollars of the public money as his own, and inasmuch as the punishment of this crime is, under the law of the United States, imprisonment for a term of years in the penitentiary, he will unquestionably give Louisville a wide berth so long as the authority of the United States shall exist here.” While Haldeman was in Bowling Green, he was named the official printer of the state’s Confederate “shadow” government. Working with Robert McKee, who also escaped arrest, he set up shop, and within less than a month, published the first issue of the Courier since its suppression. His New York Times obituary explained how he got the job done: “he established an office and an associate editor at |

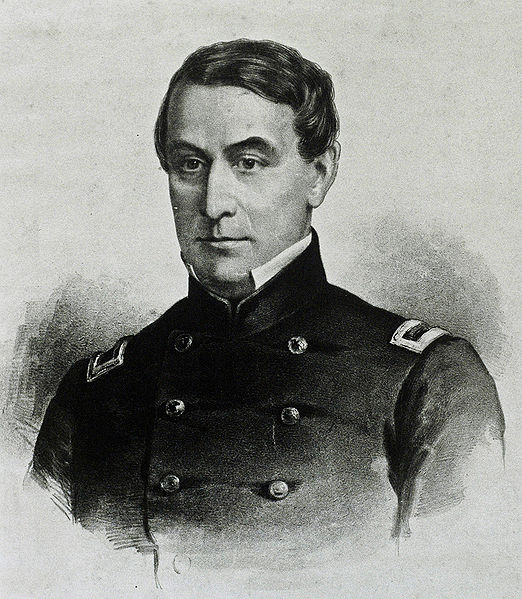

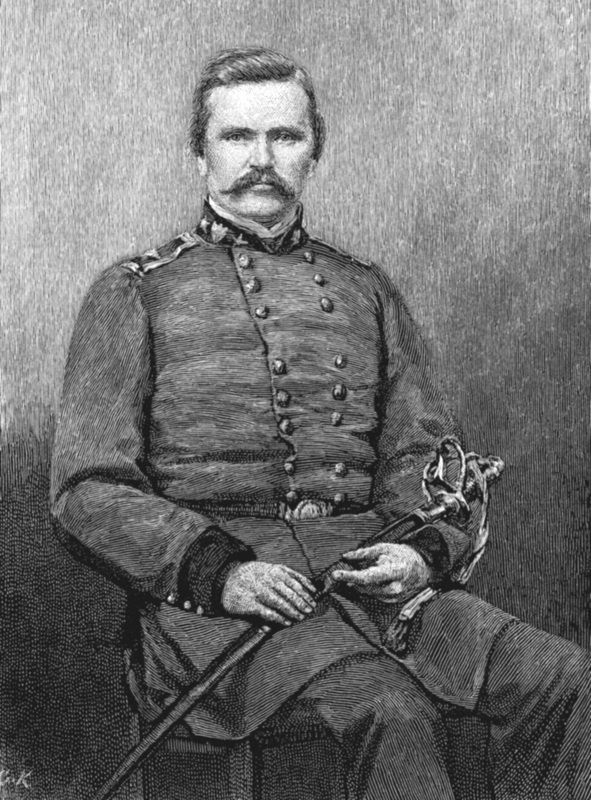

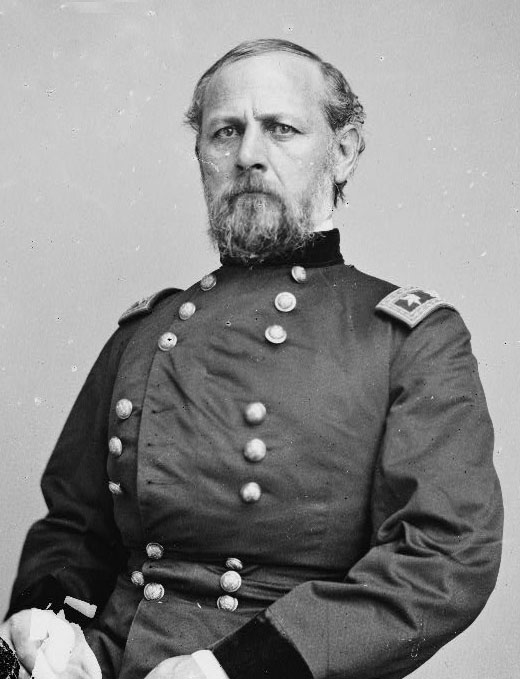

General Don Carlos Buell granted Elizabeth Haldeman and her children the travel pass that enabled them to rejoin Walter behind Confederate lines.

General Don Carlos Buell granted Elizabeth Haldeman and her children the travel pass that enabled them to rejoin Walter behind Confederate lines.

Bowling Green and then went himself to Nashville, where the paper was set up and printed.”

Left behind at Sunnyside to deal with the fallout were Elizabeth and his children. Though he’d tried to protect his assets by transferring Sunnyside’s title to Elizabeth some months before, the effort failed and troops were sent to seize the property. Legend has it that when the troops arrived, one of Haldeman’s loyal servants tried to deter them from their mission by informing them that everyone in the house was sick with scarlet fever. The ruse didn’t work. In December, Haldeman’s family joined him behind Confederate lines after being granted a travel pass by General Don Carlos Buell. But Sunnyside and his business would be auctioned off to satisfy his creditors, including the men who had signed the surety bond for his customs post.

His printing plant was first to go. It was purchased by John H. Harney, owner and editor of the Louisville Daily Democrat and one of the Courier’s competitors, for $6,150 on November 27, 1862. Sunnyside was sold on March 28, 1864 to Annie and Alexander Craig for $13,900. They renamed the home Edgewood. The Haldeman family would never live in Pewee Valley again. Elizabeth had a difficult time coming to terms with the loss of Sunnyside. While in exile, she lamented in a letter to a friend, “I so long to be at home, dear old Kentucky, is not any land like unto it.”

Meanwhile, the Confederate Army was using the Courier as a propaganda tool. The paper continued its support of southern rights, carried Se De Kay’s war correspondence and was distributed directly to Confederate troops by order of General Buckner. It continued to be printed in Nashville until February 15, 1862, when Bowling Green fell to the Union. When Nashville fell on February 16, the Haldeman family fled to Chattanooga, then to Atlanta, then to Knoxville. Publication of the Courier ceased and Haldeman went into distilling to support his growing family.

By late summer 1863, they were once again forced to flee and made their way to Madison, Georgia, where they lived for almost a year, until federal troops again forced their flight to Abbeville, South Carolina where they waited out the war.

After the Confederate surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, the family remained in Abbeville for several months, because Haldeman was uncertain of the reception he would receive in Kentucky. Arrest and imprisonment were certainly possible. His wife and children returned to Louisville in July and Haldeman himself returned in mid-August after receiving a letter from Elizabeth assuring him, “…Dr. Bemis, who is excessively anxious for your return, says that there are a number who desire to take an interest in the Courier as stockholders, many who will furnish you any amount of capital…you have hosts of friends here so anxious for your return.”

The Louisville of his homecoming was far different than the Louisville he’d left in the fall of 1861. Wildly unpopular acts by Union Army occupiers, combined with the emancipation of the slaves and their enlistment in the Union Army, had made the city’s residents much more sympathetic to the Lost Cause. Haldeman had no trouble raising the $40,000 to revive his newspaper and published his first post-war issue on December 4, 1865. In less than a year, the Courier’s circulation had outstripped both the Louisville Democrat’s and Louisville Journal’s.

Left behind at Sunnyside to deal with the fallout were Elizabeth and his children. Though he’d tried to protect his assets by transferring Sunnyside’s title to Elizabeth some months before, the effort failed and troops were sent to seize the property. Legend has it that when the troops arrived, one of Haldeman’s loyal servants tried to deter them from their mission by informing them that everyone in the house was sick with scarlet fever. The ruse didn’t work. In December, Haldeman’s family joined him behind Confederate lines after being granted a travel pass by General Don Carlos Buell. But Sunnyside and his business would be auctioned off to satisfy his creditors, including the men who had signed the surety bond for his customs post.

His printing plant was first to go. It was purchased by John H. Harney, owner and editor of the Louisville Daily Democrat and one of the Courier’s competitors, for $6,150 on November 27, 1862. Sunnyside was sold on March 28, 1864 to Annie and Alexander Craig for $13,900. They renamed the home Edgewood. The Haldeman family would never live in Pewee Valley again. Elizabeth had a difficult time coming to terms with the loss of Sunnyside. While in exile, she lamented in a letter to a friend, “I so long to be at home, dear old Kentucky, is not any land like unto it.”

Meanwhile, the Confederate Army was using the Courier as a propaganda tool. The paper continued its support of southern rights, carried Se De Kay’s war correspondence and was distributed directly to Confederate troops by order of General Buckner. It continued to be printed in Nashville until February 15, 1862, when Bowling Green fell to the Union. When Nashville fell on February 16, the Haldeman family fled to Chattanooga, then to Atlanta, then to Knoxville. Publication of the Courier ceased and Haldeman went into distilling to support his growing family.

By late summer 1863, they were once again forced to flee and made their way to Madison, Georgia, where they lived for almost a year, until federal troops again forced their flight to Abbeville, South Carolina where they waited out the war.

After the Confederate surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, the family remained in Abbeville for several months, because Haldeman was uncertain of the reception he would receive in Kentucky. Arrest and imprisonment were certainly possible. His wife and children returned to Louisville in July and Haldeman himself returned in mid-August after receiving a letter from Elizabeth assuring him, “…Dr. Bemis, who is excessively anxious for your return, says that there are a number who desire to take an interest in the Courier as stockholders, many who will furnish you any amount of capital…you have hosts of friends here so anxious for your return.”

The Louisville of his homecoming was far different than the Louisville he’d left in the fall of 1861. Wildly unpopular acts by Union Army occupiers, combined with the emancipation of the slaves and their enlistment in the Union Army, had made the city’s residents much more sympathetic to the Lost Cause. Haldeman had no trouble raising the $40,000 to revive his newspaper and published his first post-war issue on December 4, 1865. In less than a year, the Courier’s circulation had outstripped both the Louisville Democrat’s and Louisville Journal’s.

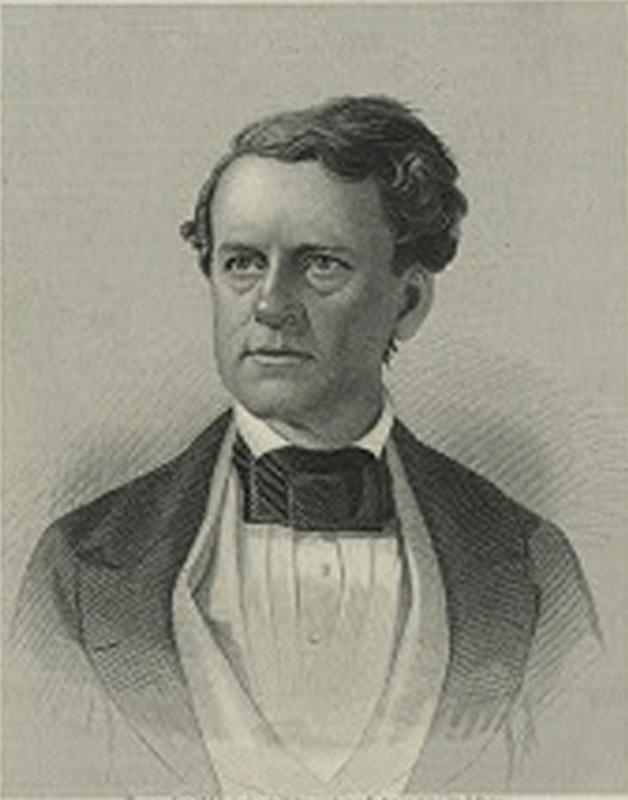

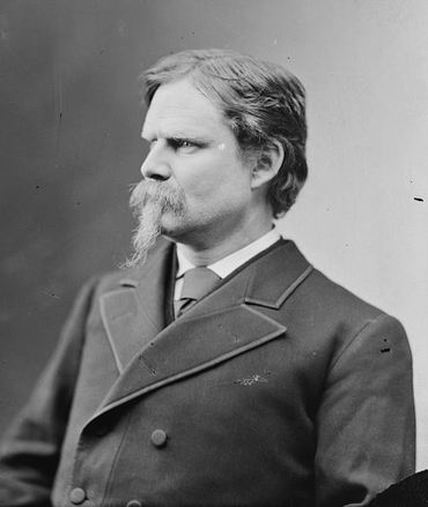

Henry Watterson is often credited with the success of the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times. The Watterson Expressway in Louisville is named for him.

Henry Watterson is often credited with the success of the Courier-Journal and Louisville Times. The Watterson Expressway in Louisville is named for him.

Around this time, an editor from Tennessee was being courted by Prentice at the Louisville Journal. The once-mighty paper had slipped and was running a poor third. Henry Watterson agreed to become editor and part-owner of the enterprise, but his real goal was to merge the Journal with Haldeman’s Courier. Watterson got his heart’s desire in 1868, when the first issue of the Courier-Journal was published on November 8.

They say that he who laughs last laughs best. The very next day, the Louisville Democrat – the paper that purchased Haldeman’s equipment during the war -- sold out to the Courier-Journal. Under Watterson’s skilled editorship, the paper went on to become a player on the national stage.

In 1884, the Courier-Journal decided to crush the upstart Evening Post with an afternoon paper of its own: the Louisville Times. The first issue hit the streets at 2:00 p.m. on May 1, 1884. Though many doubted the wisdom of Haldeman’s decision, the Louisville Times remained in circulation for over a century. The last issue was published on Valentine’s Day in 1987.

They say that he who laughs last laughs best. The very next day, the Louisville Democrat – the paper that purchased Haldeman’s equipment during the war -- sold out to the Courier-Journal. Under Watterson’s skilled editorship, the paper went on to become a player on the national stage.

In 1884, the Courier-Journal decided to crush the upstart Evening Post with an afternoon paper of its own: the Louisville Times. The first issue hit the streets at 2:00 p.m. on May 1, 1884. Though many doubted the wisdom of Haldeman’s decision, the Louisville Times remained in circulation for over a century. The last issue was published on Valentine’s Day in 1987.

In 1887, Haldeman started another venture: founding a winter resort community in Naples, Florida. The Naples Town Improvement Company built the town’s first hotel as well as a 1,000-foot dock for steamboats before selling out. The winter home Haldeman built there, however, would remain in the family until the 21st Century.

A Presbyterian by faith, Haldeman subscribed to the Calvinist work ethic. He worked six days a week, and seldom took vacations until he built his Naples villa 1,000 yards off the Gulf shore. As he aged, vacations at the villa helped him -- and many of his friends, employees and family members -- maintain his health. He generally spent time there in January, during the worst of Louisville's winter weather.

A Presbyterian by faith, Haldeman subscribed to the Calvinist work ethic. He worked six days a week, and seldom took vacations until he built his Naples villa 1,000 yards off the Gulf shore. As he aged, vacations at the villa helped him -- and many of his friends, employees and family members -- maintain his health. He generally spent time there in January, during the worst of Louisville's winter weather.

On Saturday, May 10, 1902, Walter Haldeman made a decision that cost him his life. On his walk to work, he tried to beat a street car and was hit by the front right fender and running board. Though the injuries to his head, shoulder and ankle did not appear life-threatening, by Monday afternoon, he was in intense pain and his stomach was distended. The next morning at 5:00 a.m., he died of peritonitis. He was 81.

Flags in the City of Louisville flew at half-mast, and while his body was borne to its final resting place at Cave Hill Cemetery, church bells tolled along the funeral procession's route. Hundreds of letters of condolence were received from local politicians, community leaders and fraternal and charitable organizations, as well as from newspapermen from across the country.

Flags in the City of Louisville flew at half-mast, and while his body was borne to its final resting place at Cave Hill Cemetery, church bells tolled along the funeral procession's route. Hundreds of letters of condolence were received from local politicians, community leaders and fraternal and charitable organizations, as well as from newspapermen from across the country.

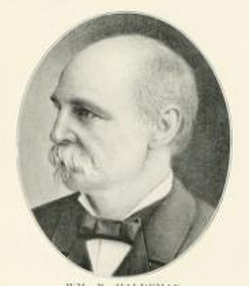

William Birch Haldeman William Birch Haldeman

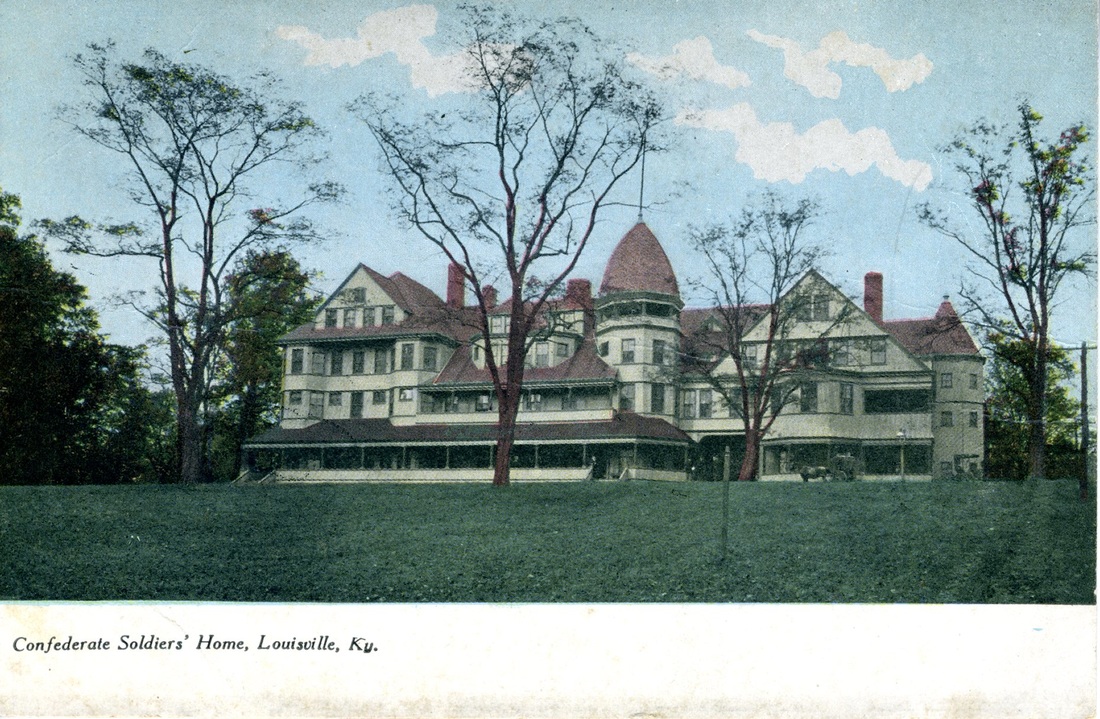

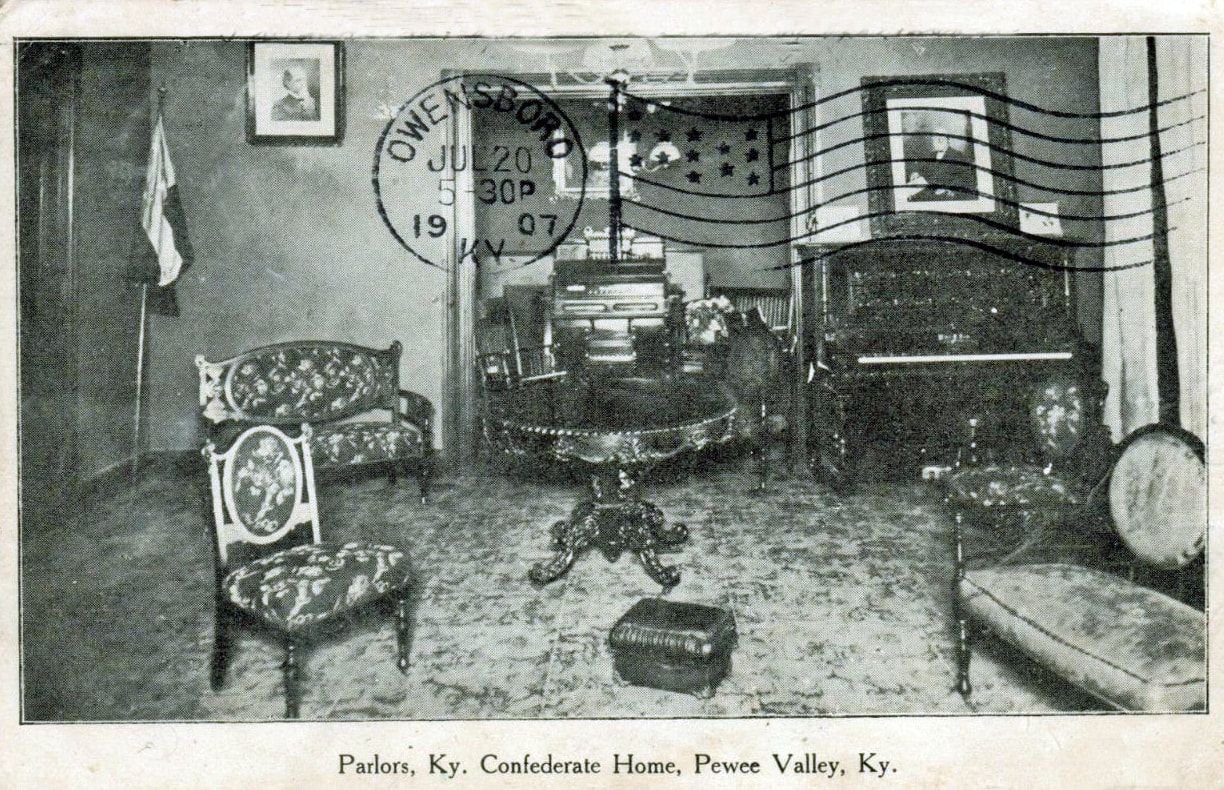

Five months to the day of his death, when the Kentucky Confederate Home opened in Pewee Valley, the parlor for named for him.

Presumably, that honor was paid for by his son, William Birch Haldeman, who remained active in Confederate Veteran affairs throughout his life. |

Portraits of Walter Newman Haldeman

Related Links