Kentucky Confederate Home

|

How the Kentucky Confederate Home Wound Up in Pewee Valley

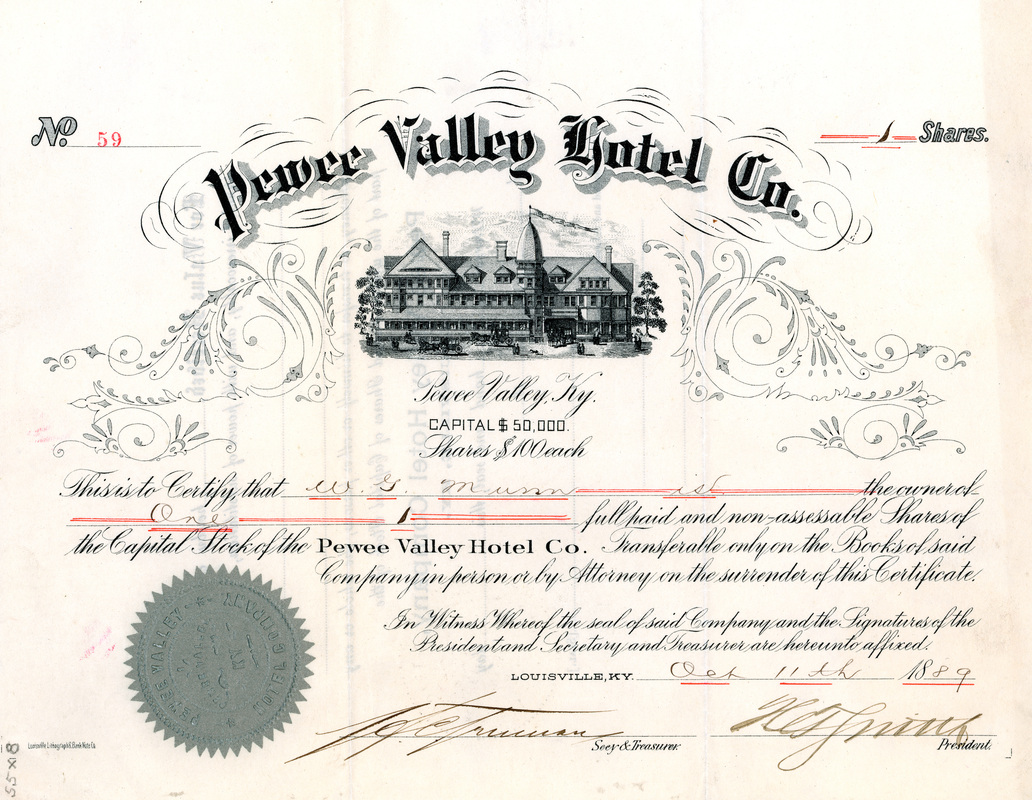

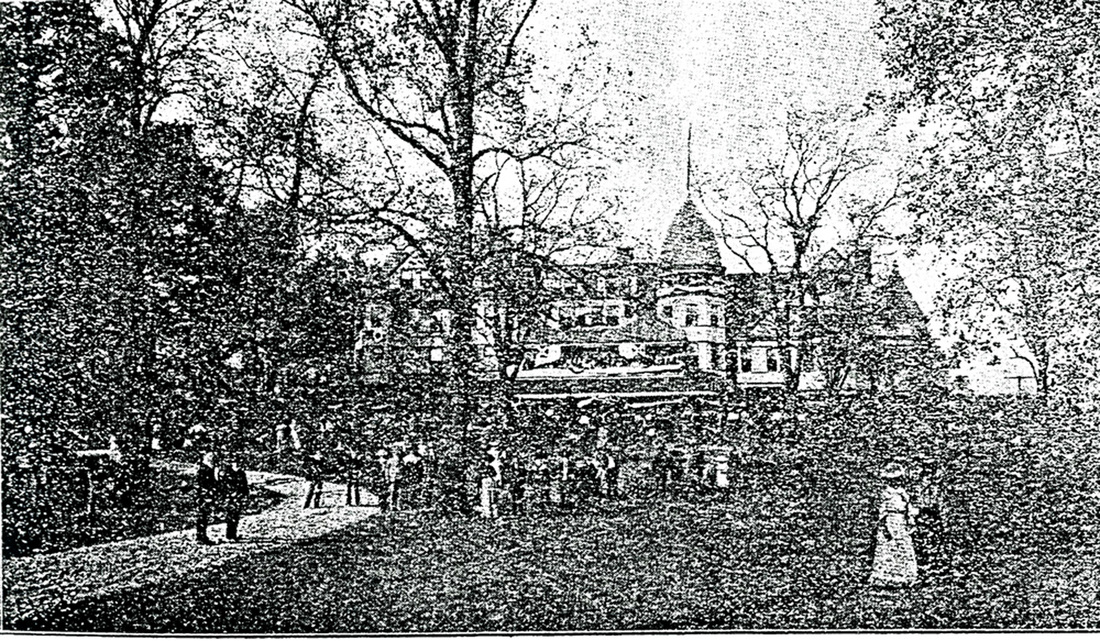

From 1902 until 1934, over 700 aged and ailing Confederate veterans were documented residents (or in turn-of-the-20th-century parlance, “inmates”) of the Kentucky Confederate Home in Pewee Valley. So how did a veterans’ home end up operating in a former luxury hotel in a small town that primarily served as a summer getaway for wealthy Louisvillians? Rusty Williams, author of My Old Confederate Home: A Respectable Place for Civil War Veterans (University of Kentucky Press, 2010), told the tale of how the Home ended up in Pewee Valley in a series of three articles published in the Call of the Pewee (December 2009, January 2010, February 2010): The Richmond, Kentucky, newspaper editor wrote a coda to the entire episode: “While a dozen other towns are tearing their hair out in their efforts to secure the Confederate Home, the citizens of Pewee Valley raise a terrible howl because they have gotten it.” After some repairs and freshening of the old Villa Ridge Inn, the Kentucky Confederate Home would open on October 23, 1902.In the spring of 1902, Pewee Valley wasn’t even in the running for the Kentucky Confederate Home. Owensboro wanted the Home. Glasgow did, too. And Bowling Green. And Frankfort. And Versailles, Nicholasville, Winchester, Bardstown and Franklin. All saw the benefits of winning the new state-funded institution: local employment and business for local merchants, visitors who would eat in local restaurants and stay in local hotels. Earlier that year (after intense lobbying by Kentucky’s ex-Confederate organizations and sympathizers) the Kentucky General Assembly had passed legislation establishing an institution to be known as the Kentucky Confederate Home. The bill required that the Confederate veterans deed to the commonwealth an appropriate residence on at least thirty acres of land, fully furnished and ready for the care and custody of at least twenty-five persons. The state would pay for the operation of the Home, but the ex-Confederates had to build it, furnish it, staff it and manage it. Governor J. C. W. Beckham appointed a board of trustees, led by Louisville attorney Bennett H. Young, to organize the Home. In May 1902, as newspaper editors across the state reminded their local merchants (and real estate promoters) that the Home would “serve as a constant source of revenue to the inhabitants of the lucky town”, the new board placed ads calling for site proposals. Pewee Valley declined to bid. Sometime shortly before the final deadline for bids, Louisville businessman A. M. Sea met informally with Bennett Young to discuss a property available in Pewee Valley. Sea was acquainted with Angus Neil Gordon, owner of the Villa Ridge Inn, a bankrupt luxury resort hotel sitting on thirty-three acres near the Pewee Valley depot. Built years before, the old hotel was a white elephant and Gordon was a motivated seller. Young suggested that Sea tell Gordon to prepare an offer. Bennett Young may have confided to Sea and Gordon something the other bidders didn’t know: the ex-Confederates were woefully short of money. Nine months before, Kentucky’s ex-Confederates had set out to raise $25,000 to finance the Home. As seed money, real estate magnate Daniel G. Parr had donated to the ex-Confederates the deed to a piece of residential property in Louisville. By the end of July 1902, as the board of trustees gathered to review more than 40 proposals, they had only about $10,000 in donations, plus the Parr house (which had a market value closer to $4,500 than to its $7,000 assessed value.) Several board members who had been appointed to prescreen all the proposals recommended the full board examine properties in Owensboro, Frankfort, Bardstown, Harrodsburg and Hawesville. The old hotel in Pewee Valley might be of interest, too. On Thursday, September 4, the board set out at 6 a.m. on a marathon one-day trip to visit all the properties. Exhausted by a day of train travel, they returned after dark to the Galt House for a late dinner and deliberations. The board agreed to take multiple ballots, with the site drawing the fewest votes to be eliminated before the next ballot. Hawesville was eliminated first. A thirty-acre plot with house and outbuildings was offered for just $5,000 (and the town would pay $3,000 of that). But the land was swampy and the water supply uncertain. Owensboro was a sentimental favorite. The offer was for a hundred level acres of tillable land, a large house and outbuildings, all on high ground with a rail line running along the property line. But at $18,000, the cost was greater than the board’s purse would allow. Owensboro was cut next. Bardstown boosters offered two tracts of sufficient acreage. Each tract was offered at $6,000, but a citizens committee raised $4,300 to put toward the purchase price of either one. The price was right, but building and furnishing a suitable home might take a year or more. Bardstown lost on the next ballot. Frankfort’s bid was for eighty acres and the old Hendrix place, once a landmark home, now a creaking ghost’s mansion overlooking the Kentucky River. The $15,000 price tag, coupled with the cost of renovating the old house, took Frankfort out of the running. The final ballot came down to a choice between Pewee Valley and Harrodsburg. The Cassell property in Harrodsburg included another landmark home. The property, home and outbuildings had a price tag of $10,500, but the merchants of Harrodsburg pledged $3,000 for furnishings and improvements. Rail connections to Harrodsburg were spotty, but the town was close to the geographic center of Kentucky and almost equidistant from Lexington, Frankfort and Louisville. In Pewee Valley, the Villa Ridge Inn was in good repair and fully furnished. The old hotel had seventy-two guest rooms, a dining hall and kitchen, running water, steam heat and gas lighting. Gordon wanted $8,000 in cash and Parr’s Louisville property. The price was right; the trustees could divest themselves of the Parr property, pay Gordon and still hold about $2,000 cash in hand. Pewee Valley was only thirty minutes by train from the busy Louisville railway hub, so it was accessible to visitors. Villa Ridge Inn could house up to a hundred residents in a building meant for institutional use, and it was ready for immediate occupancy with just a bit of sprucing up. The final ballot tallied six for Harrodsburg and nine for Pewee Valley. Before retiring for the night after their twenty-hour day of travel and deliberation, board members called in a waiting reporter from the Courier-Journal to announce that the Kentucky Confederate Home would open in Pewee Valley two months later. No one anticipated the firestorm that would erupt in Pewee Valley the next day. By most accounts Judge P. B. Muir, who owned a home in Pewee Valley, was a reasonable man: patient and slow to anger. Eighty years old, he was semi-retired from a lifelong career in the legal profession, and to his Pewee Valley neighbors he exhibited the same even temper he had shown from the bench. But vitriol dripped from every sentence of the statement he delivered to the Courier-Journal on September 5, 1902, the day after Bennett H. Young and the Kentucky Confederate Home board, announced they had chosen the old Villa Ridge Inn in Pewee Valley as the site of the new institution. “The people don’t want such a home here,” Muir said. “The people of Pewee Valley believe that such an institution of the kind must hurt the place.” The judge vowed that the decision would not be allowed to stand. Muir wasn’t alone in his opposition. His son-in-law Harry Weissinger, a Louisville tobacco manufacturer who had spent many a summer beneath the shady oaks that lent Judge Muir’s Pewee Valley estate its name and a Confederate veteran himself, sent a public telegram to the Home board withdrawing his $300 pledge. “Among the summer residents of Pewee Valley the feeling against the Home is undoubtedly strong,” newspapers noted. They described Pewee Valley as one of the “most fashionable suburbs about Louisville, and the people seem a bit discomfited by the advent of this public benevolent institution.” Perhaps Muir and other Pewee Valley residents were looking up the road at Anchorage and the Lakeland Asylum. Lakeland Asylum—actually, the Central Kentucky Asylum for the Insane—was a grim, state-operated nineteenth century warehouse for the insane, the retarded and the brain damaged. Anchorage residents could hear heart-ripping moans echoing from the asylum at all hours; they feared having the institution’s criminally insane near their schools and homes. The Kentucky Confederate Home, however, was an institution of an entirely different sort. In the wake of America’s Civil War more than 40,000 Kentucky men who had worn the gray returned to the Bluegrass. Most Confederate veterans returned home to live quiet, productive lives. But some—due to lingering war wounds, mental confusion, disability, infirmity, age or just plain bad luck—were unable to cope with postwar life. For Kentucky’s ex-Confederates there was no institutional support, no pension, no veterans’ benefits. By the 1880s, disabled Confederate veterans grew more visible on the streets and alleys of Louisville, Frankfort and Lexington. Most small towns knew of at least one veteran unable to feed himself or his family. |

|

Informally at first, then as part of organized groups, Kentucky’s Confederate veterans, their wives, sisters and daughters began caring for their own. By the end of the nineteenth century, more than 3,500 ex-Confederates and 4,000 women were active in local United Confederate Veterans camps and United Daughters of the Confederacy chapters. Despite its not-quite-Union-not-quite-Confederate statusduring the Civil War, Kentucky’s memory of often oppressive Union occupation resulted in the commonwealth becoming more “Southern” in the postwar years than it had ever been during the conflict. At the same time, Kentucky politicians recognized the public’s sympathy for their Confederate veterans and the potential for a solid bloc of Democratic votes.

At the dawn of the new century, Kentucky’s ex-Confederates set out to build and support a luxurious refuge where disabled and impoverished comrades could spend their final days in comfort and free from want. The general public supported a Home with their hearts and purses; the state legislature voted funds sufficient to operate it in a manner far superior to the publicly funded almshouses, poor farms or asylums typical of the time.

The Kentucky Confederate Home was intended to be a respectable place for old men—farmers, factory workers, trainers, traders, politicians and professionals—who needed help in their final years.

“We are proud of the old Confederates,” Judge Muir told a reporter, but he and his neighbors would fight the institution tooth and nail. Pewee Valley Mayor H. M. Woodruff promised protest meetings of the town’s citizens.

Muir’s first step was a personal appeal to Governor Beckham. Beckham, who was counting on ex-Confederate votes to return him to the statehouse, didn’t respond to Muir’s telegrams. When Muir threatened a lawsuit to overturn the legislation that established the Home, the state’s attorney general ruled in support of the act.

Most Kentuckians believed the protest was a petty and snobbish one. “There is too much aristocracy at Pewee Valley to permit poor and crippled Confederate veterans to be seen perambulating the place from day to day,” one newspaper editor snorted.

In the end, the tempest blew itself out. The Board of Trustees patiently explained the unique benefits of the Pewee Valley site to newspaper reporters; the governor supported the choice, and plans continued to have the Home operational by the end of October.

The opening and dedication was the largest gathering of Kentucky’s ex-Confederates, their families and supporters since the end of America’s Civil War thirty-seven years earlier. Ten thousand men and women from all sections of Kentucky would gather in Pewee Valley for a day of bands, bunting, oration and celebration.

The "Big Train" and the "Little Train" that brought visitors to the Kentucky Confederate Home. From the Norris Summers collection, courtesy Bethany Major.

The "Big Train" and the "Little Train" that brought visitors to the Kentucky Confederate Home. From the Norris Summers collection, courtesy Bethany Major.

The first arrivals were farmers from the neighboring countryside, and they tied their wagons to the snake fence alongside the rail tracks. By 11 a.m. the broad lawn surrounding the four-story former resort hotel was jammed, and more celebrants were arriving every minute by cart, carriage, trolley, train and the occasional motorcar. Pewee Valley’s churchwomen set out food and lemonade on outdoor tables, while clubwomen from throughout the state distributed hampers of picnic fare.

The day was bright and warm, altogether glorious weather for late October.

Every hour, it seemed, another thousand men and women of all ages and from all parts of the state arrived for the celebration. Kentucky’s major newspapers had given the dedication front-page play in the early editions, and the crowd was ready for a spectacle.

A special train carrying dignitaries arrived from Louisville at one o’clock, followed soon after by a train from Frankfort carrying Gov. J. C. W. Beckham, the two United States senators, dozens of state legislators and more civic notables. Wild cheers greeted the arriving dignitaries as they were led for an inspection into the grand building they would later dedicate for the use of Kentucky’s invalid and indigent Confederate veterans.

Located on the crest of a gentle slope just a few hundred yards from the Pewee Valley train depot, the old Villa Ridge Inn stood four stories high, sixty feet deep and as long as seven rail cars. A wide veranda, furnished with comfortable rocking chairs and wooden gliders, surrounded the building on three sides, and it was said residents could enjoy a mile-long covered stroll. Second-story balconies and generous windows on every floor provided splendid views of area homes and churches as well as natural cross-ventilation. Atop the frame building was an octagonal cupola and, atop the cupola, eighty feet above neat flower beds, was a flagpole from which on this day flew the United States and Confederate flags.

Just inside the main entrance on the ground floor were a richly paneled lobby and a book-lined library. The parlor furniture was carved, massive, dark and comfortable. Two additional parlors and a smoking room opened off a wide hallway that ran the length of the building to the dining room. Victorian paintings or pressed ferns hung on every wall and sprays of fresh flowers appeared on every horizontal surface. Surrounded on three sides by large windows, the dining room would seat eighty persons for formal servings, but could be increased to more than a hundred for casual meals, and the adjoining kitchen was equipped with institutional stoves, ovens, coolers and prep tables.

Three curving wooden stairways provided access to the upper floors, one in the center of the building and one on either end. Upstairs sleeping rooms and bathrooms opened off central hallways of wide waxed floorboards; large linen presses and servants’ pantries were hidden at convenient distances throughout the halls. The upstairs guestroom floors were covered with matting, while the hallways and all downstairs rooms were carpeted.

At two o’clock sharp—to the strains of “My Old Kentucky Home”—the governor, the chairmen of the various dedication committees and the invited orators ended their tour and filed onto a temporary platform erected on the driveway in front of the Home.

After a short invocation, Bennett H. Young, president of the Home’s board and master of ceremonies, called H. M. Woodruff, mayor of Pewee Valley, to the podium. Obsequious as a hotel desk clerk, Woodruff began with a half-hearted apology for the town’s earlier opposition to the Kentucky Confederate Home. “We feel somewhat like the old folks did when the daughter ran off and married the man of her choice: after the knot was tied, the best thing was to receive the young couple back into the bosom of the family.”

Pewee Valley had nothing against the Confederates, he explained. “Had a proposition been made to locate a Federal home within the limits of the town, it would have met with the same opposition.”

Finally, a perspiring Mayor Woodruff bowed to the inevitable: “It seems to be the proper thing to give you a hearty welcome and try to make you feel at home.”

Amid only a smattering of applause, the mayor returned to his seat. Pewee Valley’s mayor was only a warm-up act, however.

General Joseph H. Lewis, commander of Kentucky’s Orphan Brigade, made a rousing speech to his former troops; Laura Talbot Galt, the little Louisville girl who was expelled from school for refusing to sing “Marching Through Georgia”, was presented to the crowd; Governor Beckham read brief remarks accepting the Home on behalf of the state; and Bennett Young delivered a Lost Cause oration of the classic style.

There had never been (nor would there ever be again) such a gathering of Kentucky Confederates, their families and their friends as on that October day in Pewee Valley. Among the dedication speakers that afternoon was W. T. Ellis, former Confederate cavalryman and popular U. S. Congressman from Owensboro. The crowd interrupted Ellis time after time with thunderous applause during his hour-long oration, but he earned the greatest roars of approval when he spoke of the debt his audience owed men of the Confederate generation:

“The young men Kentucky gave to the Confederate army rendered their state some service,” he bellowed from the podium, “and are, as they and their friends believe, entitled to a respectable place in its history.”

The Kentucky Confederate Home proved to be a respectable—though not always idyllic—place where disabled and impoverished veterans could spend their final days in comfort and free from want.

Nearly a thousand Confederate veterans who had need of sustenance or care would find comfortable refuge here in Pewee Valley from 1902 to 1934.

The day was bright and warm, altogether glorious weather for late October.

Every hour, it seemed, another thousand men and women of all ages and from all parts of the state arrived for the celebration. Kentucky’s major newspapers had given the dedication front-page play in the early editions, and the crowd was ready for a spectacle.

A special train carrying dignitaries arrived from Louisville at one o’clock, followed soon after by a train from Frankfort carrying Gov. J. C. W. Beckham, the two United States senators, dozens of state legislators and more civic notables. Wild cheers greeted the arriving dignitaries as they were led for an inspection into the grand building they would later dedicate for the use of Kentucky’s invalid and indigent Confederate veterans.

Located on the crest of a gentle slope just a few hundred yards from the Pewee Valley train depot, the old Villa Ridge Inn stood four stories high, sixty feet deep and as long as seven rail cars. A wide veranda, furnished with comfortable rocking chairs and wooden gliders, surrounded the building on three sides, and it was said residents could enjoy a mile-long covered stroll. Second-story balconies and generous windows on every floor provided splendid views of area homes and churches as well as natural cross-ventilation. Atop the frame building was an octagonal cupola and, atop the cupola, eighty feet above neat flower beds, was a flagpole from which on this day flew the United States and Confederate flags.

Just inside the main entrance on the ground floor were a richly paneled lobby and a book-lined library. The parlor furniture was carved, massive, dark and comfortable. Two additional parlors and a smoking room opened off a wide hallway that ran the length of the building to the dining room. Victorian paintings or pressed ferns hung on every wall and sprays of fresh flowers appeared on every horizontal surface. Surrounded on three sides by large windows, the dining room would seat eighty persons for formal servings, but could be increased to more than a hundred for casual meals, and the adjoining kitchen was equipped with institutional stoves, ovens, coolers and prep tables.

Three curving wooden stairways provided access to the upper floors, one in the center of the building and one on either end. Upstairs sleeping rooms and bathrooms opened off central hallways of wide waxed floorboards; large linen presses and servants’ pantries were hidden at convenient distances throughout the halls. The upstairs guestroom floors were covered with matting, while the hallways and all downstairs rooms were carpeted.

At two o’clock sharp—to the strains of “My Old Kentucky Home”—the governor, the chairmen of the various dedication committees and the invited orators ended their tour and filed onto a temporary platform erected on the driveway in front of the Home.

After a short invocation, Bennett H. Young, president of the Home’s board and master of ceremonies, called H. M. Woodruff, mayor of Pewee Valley, to the podium. Obsequious as a hotel desk clerk, Woodruff began with a half-hearted apology for the town’s earlier opposition to the Kentucky Confederate Home. “We feel somewhat like the old folks did when the daughter ran off and married the man of her choice: after the knot was tied, the best thing was to receive the young couple back into the bosom of the family.”

Pewee Valley had nothing against the Confederates, he explained. “Had a proposition been made to locate a Federal home within the limits of the town, it would have met with the same opposition.”

Finally, a perspiring Mayor Woodruff bowed to the inevitable: “It seems to be the proper thing to give you a hearty welcome and try to make you feel at home.”

Amid only a smattering of applause, the mayor returned to his seat. Pewee Valley’s mayor was only a warm-up act, however.

General Joseph H. Lewis, commander of Kentucky’s Orphan Brigade, made a rousing speech to his former troops; Laura Talbot Galt, the little Louisville girl who was expelled from school for refusing to sing “Marching Through Georgia”, was presented to the crowd; Governor Beckham read brief remarks accepting the Home on behalf of the state; and Bennett Young delivered a Lost Cause oration of the classic style.

There had never been (nor would there ever be again) such a gathering of Kentucky Confederates, their families and their friends as on that October day in Pewee Valley. Among the dedication speakers that afternoon was W. T. Ellis, former Confederate cavalryman and popular U. S. Congressman from Owensboro. The crowd interrupted Ellis time after time with thunderous applause during his hour-long oration, but he earned the greatest roars of approval when he spoke of the debt his audience owed men of the Confederate generation:

“The young men Kentucky gave to the Confederate army rendered their state some service,” he bellowed from the podium, “and are, as they and their friends believe, entitled to a respectable place in its history.”

The Kentucky Confederate Home proved to be a respectable—though not always idyllic—place where disabled and impoverished veterans could spend their final days in comfort and free from want.

Nearly a thousand Confederate veterans who had need of sustenance or care would find comfortable refuge here in Pewee Valley from 1902 to 1934.

Related Links:

Pewee Valley's Side of the Kentucky Confederate Home Story

A Visit to the Kentucky Confederate Home in 1915

What Became of the Home

The Confederate Burying Ground at Pewee Valley Cemetery

Videos of the 2010 Confederate Memorial Day Observation

1906 Kentucky Confederate Home Insurance Map

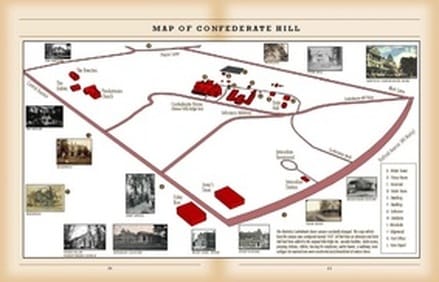

Confederate Hill Map, 2010