The Caboose at Town Square

Any Peweean who has ever had to give directions to a location off Central Avenue has probably said, "Look for the red caboose." It's been a local landmark since April 26, 1971.

Aside from pointing the way to Town Hall, the Pewee Valley Vet, the 314 Exchange and the Little Colonel Playhouse, what's a caboose doing in the middle of town?

That caboose is actually the result of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that came about in the late 1960s-early 1970s. Peweean Don Blevins had placed a bid with the L&N Railroad for a caboose to put in his backyard. After waiting two years, he was successful, but had lost interest in the project. So he asked the Pewee Valley Mayor at the time, John Frith Stewart, if the City might be interested.

The City was. But they didn't buy it. They negotiated with L&N and got the caboose -- and had it delivered to downtown Pewee Valley -- free of charge, in memory of Charles Frith, the Mayor's dad and a retired L&N employee. Its acquisition marked the grand finale to the town's year-long Centennial Celebration.

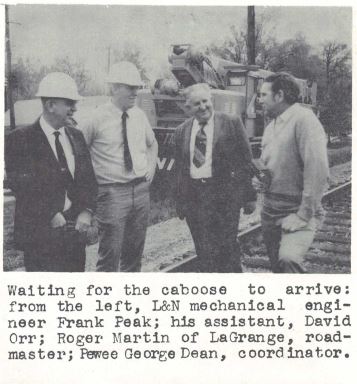

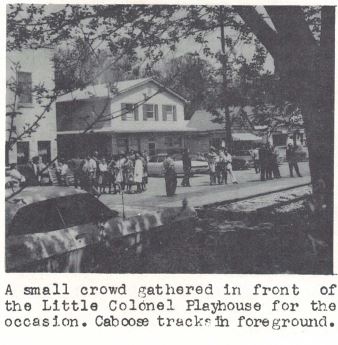

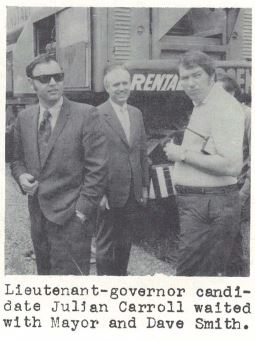

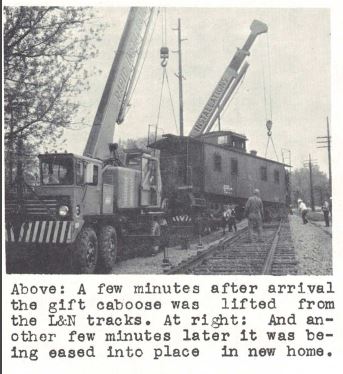

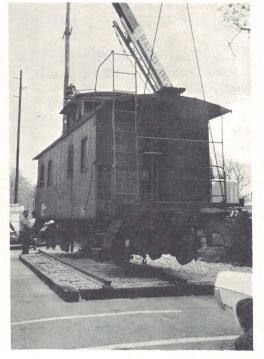

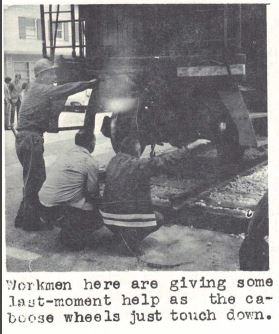

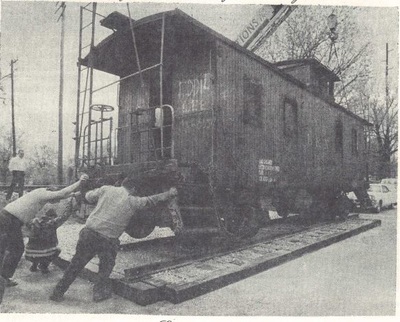

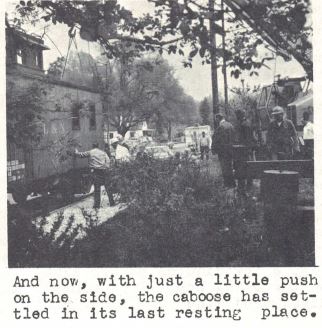

Councilman George Dean coordinated the project with expert assistance from L&N Trainmaster Woodby; purchasing agent Andy Johnson; and mechanical engineer Frank Peak and his assistant David Orr. The City spent $26 on the two, 90-pound, 13-foot sections of track the caboose sits on and got the spikes and cross-ties donated. An all-volunteer crew of 18 Peweeans laid the track, including Councilman Dean, Mayor Frith and his two sons. Another Peweean, David Smith, secured the free use of two huge cranes to swing the caboose onto its new resting spot, right where the Interurban ran through town from 1901 to 1934.

Councilman George Dean coordinated the project with expert assistance from L&N Trainmaster Woodby; purchasing agent Andy Johnson; and mechanical engineer Frank Peak and his assistant David Orr. The City spent $26 on the two, 90-pound, 13-foot sections of track the caboose sits on and got the spikes and cross-ties donated. An all-volunteer crew of 18 Peweeans laid the track, including Councilman Dean, Mayor Frith and his two sons. Another Peweean, David Smith, secured the free use of two huge cranes to swing the caboose onto its new resting spot, right where the Interurban ran through town from 1901 to 1934.

Moving the Caboose: Photos from the April 1971 Call of the Pewee

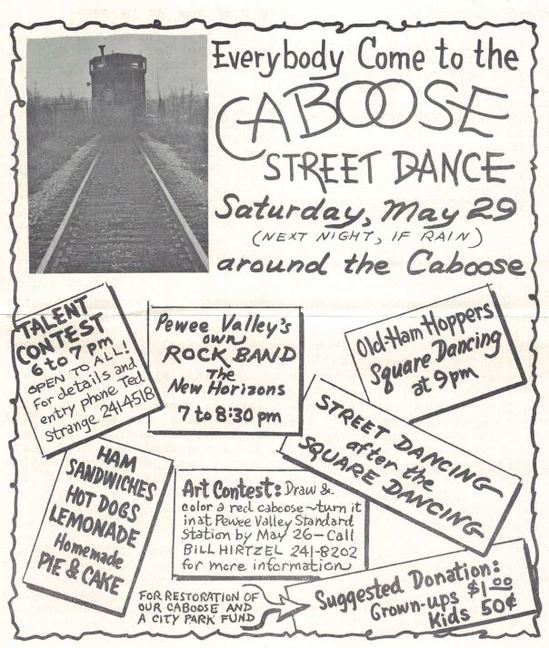

Once the caboose was in place, the next step was painting it and refurbishing the interior. The Porter Paint Company donated the red paint for the exterior. To raise the rest of the money, the City sold additional copies of "A Place Called Pewee Valley" for 75 cents at Beard's Grocery and other locales and hosted a Memorial Day weekend dance on May 29.

The May 1971 Call of the Pewee wryly noted:

Anyone who would have said, a year ago, "Someday there will be a bunch of Pewees dancing around a caboose smack dab in the center of town" would have been looked upon as a person who had lost the last of his marbles...

Crazy or not, the street dance was a smashing success. Several hundred attended, and the event raked in a grand total of $420.

Once the caboose was in place, the next step was painting it and refurbishing the interior. The Porter Paint Company donated the red paint for the exterior. To raise the rest of the money, the City sold additional copies of "A Place Called Pewee Valley" for 75 cents at Beard's Grocery and other locales and hosted a Memorial Day weekend dance on May 29.

The May 1971 Call of the Pewee wryly noted:

Anyone who would have said, a year ago, "Someday there will be a bunch of Pewees dancing around a caboose smack dab in the center of town" would have been looked upon as a person who had lost the last of his marbles...

Crazy or not, the street dance was a smashing success. Several hundred attended, and the event raked in a grand total of $420.

Scene at the Caboose Street Dance from the June 1971 Call of the Pewee

Scene at the Caboose Street Dance from the June 1971 Call of the Pewee

Writing from Los Angeles, Lillian Fletcher Brackett sent Call of the Pewee Editor Lee Heiman this reminiscence about cabooses, love and romance in Pewee Valley, reprinted in the May 1971 Call:

A memory, which might be of this very same caboose, was hearing the Matthewses tell of coming home from Macauley's Theatre, and it being too late for the last passenger train, they rode the caboose of a local freight and it was quite the gayest party imaginable. Some L&N officials lived in Pewee Valley, so it was the usual thing for belles and beaux to do. Many a romance had its start, or finish, right there.

About Our Caboose

Peweean Greg Rose, who worked in the railroad repair yard for some years, says our caboose was made of wood in the South Louisville Shop. Because they weren't assigned to certain trains, cabooses traveled for millions of miles and were standard features on every freight train until the 1980s.

Cabooses were manned by a brakeman and flagman. Before automatic air brakes, it was the brakeman's job to twist the brakewheels atop the cars with a stout club when the engineer signaled with his whistle that he wanted to stop or slow down. When the train stopped, the flagman jumped out and used lanterns and warning flags to stop any approaching trains.

While the train was in motion, the brakeman and flagman would use the caboose's cupola and large window to watch for signs of trouble. Lanterns were used to communicate with the engineer.

The caboose also served as the train conductor's office. It was where printed "waybills" were kept for every freight car from its origin to its destination. Conductors monitored where the trains were and where to drop cars off.

Technology rendered the caboose obsolete. Computers have taken over the conductor's function. Rail sensors monitor cars for fires, axle problems and dragging items, and radio technology controls the brakes.

Lee Heiman, in the March 1989 Call of the Pewee, provided some additional historical background on cabooses:

THERE'S A WORD FOR IT...CRUMMY

We've just learned -- honestly! -- that "crummy" is railroad slang for a caboose.

The word "caboose" comes from an old Dutch work meaning cookhouse. During their runs, trainmen cooked and ate in their cabooses, and veteran railroaders recall that if anyone dropped a single crumb, the crew would really raise cain.

So, you can see, "crummy" is sort of a natural nickname. The caboose wasn't just a dining car, but an office and home-away-from home, too.

The first ones were merely converted boxcars. In the 1840s, as railcars began to make longer runs, they fitted out smaller freight cars with stoves and desks.

Second-story cupolas, a development of the Civil War era, allowed better visibility, as did the bay window, which largely replaced the cupola.

Today's freight trains, roaring along without their once-familiar tail-ends, look as if they've forgotten and left something behind.

Cabooses were manned by a brakeman and flagman. Before automatic air brakes, it was the brakeman's job to twist the brakewheels atop the cars with a stout club when the engineer signaled with his whistle that he wanted to stop or slow down. When the train stopped, the flagman jumped out and used lanterns and warning flags to stop any approaching trains.

While the train was in motion, the brakeman and flagman would use the caboose's cupola and large window to watch for signs of trouble. Lanterns were used to communicate with the engineer.

The caboose also served as the train conductor's office. It was where printed "waybills" were kept for every freight car from its origin to its destination. Conductors monitored where the trains were and where to drop cars off.

Technology rendered the caboose obsolete. Computers have taken over the conductor's function. Rail sensors monitor cars for fires, axle problems and dragging items, and radio technology controls the brakes.

Lee Heiman, in the March 1989 Call of the Pewee, provided some additional historical background on cabooses:

THERE'S A WORD FOR IT...CRUMMY

We've just learned -- honestly! -- that "crummy" is railroad slang for a caboose.

The word "caboose" comes from an old Dutch work meaning cookhouse. During their runs, trainmen cooked and ate in their cabooses, and veteran railroaders recall that if anyone dropped a single crumb, the crew would really raise cain.

So, you can see, "crummy" is sort of a natural nickname. The caboose wasn't just a dining car, but an office and home-away-from home, too.

The first ones were merely converted boxcars. In the 1840s, as railcars began to make longer runs, they fitted out smaller freight cars with stoves and desks.

Second-story cupolas, a development of the Civil War era, allowed better visibility, as did the bay window, which largely replaced the cupola.

Today's freight trains, roaring along without their once-familiar tail-ends, look as if they've forgotten and left something behind.

Downtown Pewee Valley with Caboose as Seen Through a Fish-Eye Lens: Photos by Richard Duncan for the February 1972 Call of the Pewee

Related Links