The Little Train of Long Ago: Reminiscences of Iris Haskins

|

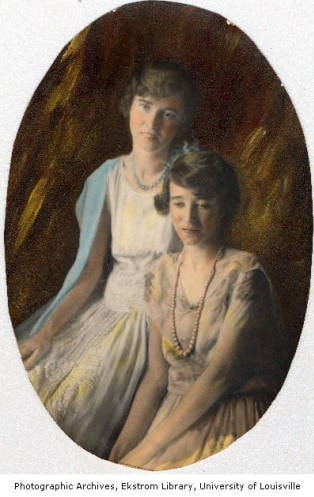

The Robert Lee and Almira Goodloe Haskins family lived in Altawood, just outside the Pewee Valley city limits, from about 1915 into the 1940s. R.L. was a contractor. His college-educated daughters, Elizabeth and Iris, later went into teaching at Ahrens Trade School in Louisville.

During the 1960s, Iris wrote about her memories of Pewee Valley, including a section of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church's cookbook focusing on the "Little Colonel" and time-honored repasts and a Courier-Journal story about Christmas traditions. The following story about the trains appeared in the January 1, 1968 Courier-Journal Sunday Magazine. |

Nostalgia for the days when I rode the train into town almost overwhelms me at times when I ride on the modern expressways. Jangled nerves and frayed temper are often the result of the traffic jams, the roar of the trucks, the scream of brakes. To think we traded the calmness of train travel for this. Yet, as I rode the train to school in those long-ago days, I longed for my 18th birthday and permission to drive Dad's Model T.

In Pewee Valley, our neighborhood was served by trains that became so much a part of our lives that we personified them and spoke of them as friends. Our sentiment was summed up by an old lady, who lived far back in the country and came in with her grandson in his two-horse wagon to pick up some freight at the station. She had heard people talk about trains and had heard the whistle in the far distance, but this was the first time she had seen one. The train was standing at the station, letting off steam in the frosty air. She went up to it, gently patted the engine, and said, " You pore old thing. Folks mighty nigh run you to death."

Whether one rode the trains in or out of Pewee Valley had no bearing to their importance to one's way of life. Mr Tom, the old man who held up the "STOP" sign at the crossing when the trains came through, is an example. Between trains he sat in the station with his chair tilted against the wall, chewed his tobacco, gossiped with the other loafers or dozed. A newcomer in the community asked if he would do some work elsewhere for an hour or so. Mr. Tom pulled himself erect and declared, " I have a position. I handle the 'Pan' and the 'Little Train.'"

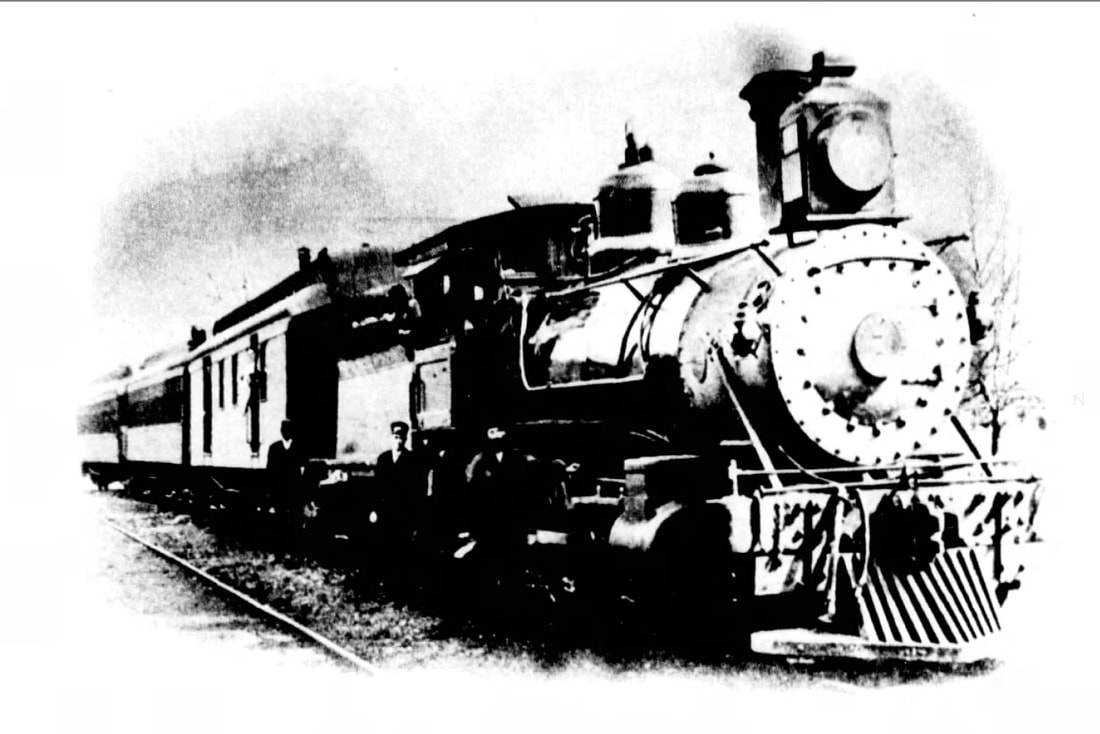

Our day began with a train and ended with a train. The first was the "Little Train," a commuter train that began its run at 6:30 a.m. in Eminence. It came through New Castle (editor's note: Ms. Haskins was mistaken. The train never came through New Castle), LaGrange, Crestwood, arrived in Pewee Valley at 7 a.m, then went on to Anchorage, Lyndon and Louisville. The whole journey was about 50 miles. The train was used by people who worked in the Louisville & Nashville Railroad offices and by those bound for a day's shopping or some business dealings in Louisville. Because Pewee Valley had no high school, the teen-agers (sic) rode the train to Anchorage or Louisville to school.

The householders in the towns along the way checked their clocks and watches with the whistle of the "Little Train." Its first whistle as it approached a town was a signal to commuters to drink that last swallow of coffee; finish primping, tie that necktie. The next time the whistle blew it meant one should be out the door and on the way to the station.

There would be sleepyheads for whom the whistle blew once more to make them hurry. After the stop at the station, the "Little Train" would move slowly out of town. Latecomers swung aboard somewhat disheveled. Dresses were buttoned and collars put on in coach washrooms.

The conductor, engineer and fireman felt a real responsibility for their passengers. They were on first-name terms with most. There was good-natured banter when latecomers boarded.

A chronically-tardy Pewee Valley passenger was a Mr. Stone. (Editor's note: Walter Stone, his wife Mamie, his widowed daughter Florence Carter, and her two children, Margaret and Walter, lived at 100 Ashwood Avenue in the home now known as the Washburne-Waterfill House. He worked in the hardware industry, possibly at Belknap in downtown Louisville.) Other commuters made bets on whether he'd make the train. You could see him cutting through backyards, waving an umbrella that he carried winter and summer, shouting, "Wait! Hold the train! I'm coming!"

He boarded, puffing and protesting, "You're ahead of schedule again!" Nine times out of ten he made the train, but when he didn't the bets were paid off.

The "Little Train" had two coaches and a baggage car. By the time the Pewee Valley passengers got on, the coaches were almost filled. Because Mr. Stone was known to be a tightwad, the other passengers, just for fun, would spread out until there was not an empty seat to be seen when he got on.

The target of their joke would stand between the two coaches, looking down each aisle. "Who'll let me have a seat to town for a dime?" he would bark. The others would suddenly be sleepy or immersed in the newspaper or engrossed in conversation.

The undaunted Mr. Stone would pound the floor with his umbrella. "Who'll let me have a seat for a quarter!" Again he would be ignored. Pounding again, he would shout a higher offer, "Fifty cents!" Someone then would get up leisurely, collect a half-dollar from Mr. Stone and surrender a seat.

In Pewee Valley, our neighborhood was served by trains that became so much a part of our lives that we personified them and spoke of them as friends. Our sentiment was summed up by an old lady, who lived far back in the country and came in with her grandson in his two-horse wagon to pick up some freight at the station. She had heard people talk about trains and had heard the whistle in the far distance, but this was the first time she had seen one. The train was standing at the station, letting off steam in the frosty air. She went up to it, gently patted the engine, and said, " You pore old thing. Folks mighty nigh run you to death."

Whether one rode the trains in or out of Pewee Valley had no bearing to their importance to one's way of life. Mr Tom, the old man who held up the "STOP" sign at the crossing when the trains came through, is an example. Between trains he sat in the station with his chair tilted against the wall, chewed his tobacco, gossiped with the other loafers or dozed. A newcomer in the community asked if he would do some work elsewhere for an hour or so. Mr. Tom pulled himself erect and declared, " I have a position. I handle the 'Pan' and the 'Little Train.'"

Our day began with a train and ended with a train. The first was the "Little Train," a commuter train that began its run at 6:30 a.m. in Eminence. It came through New Castle (editor's note: Ms. Haskins was mistaken. The train never came through New Castle), LaGrange, Crestwood, arrived in Pewee Valley at 7 a.m, then went on to Anchorage, Lyndon and Louisville. The whole journey was about 50 miles. The train was used by people who worked in the Louisville & Nashville Railroad offices and by those bound for a day's shopping or some business dealings in Louisville. Because Pewee Valley had no high school, the teen-agers (sic) rode the train to Anchorage or Louisville to school.

The householders in the towns along the way checked their clocks and watches with the whistle of the "Little Train." Its first whistle as it approached a town was a signal to commuters to drink that last swallow of coffee; finish primping, tie that necktie. The next time the whistle blew it meant one should be out the door and on the way to the station.

There would be sleepyheads for whom the whistle blew once more to make them hurry. After the stop at the station, the "Little Train" would move slowly out of town. Latecomers swung aboard somewhat disheveled. Dresses were buttoned and collars put on in coach washrooms.

The conductor, engineer and fireman felt a real responsibility for their passengers. They were on first-name terms with most. There was good-natured banter when latecomers boarded.

A chronically-tardy Pewee Valley passenger was a Mr. Stone. (Editor's note: Walter Stone, his wife Mamie, his widowed daughter Florence Carter, and her two children, Margaret and Walter, lived at 100 Ashwood Avenue in the home now known as the Washburne-Waterfill House. He worked in the hardware industry, possibly at Belknap in downtown Louisville.) Other commuters made bets on whether he'd make the train. You could see him cutting through backyards, waving an umbrella that he carried winter and summer, shouting, "Wait! Hold the train! I'm coming!"

He boarded, puffing and protesting, "You're ahead of schedule again!" Nine times out of ten he made the train, but when he didn't the bets were paid off.

The "Little Train" had two coaches and a baggage car. By the time the Pewee Valley passengers got on, the coaches were almost filled. Because Mr. Stone was known to be a tightwad, the other passengers, just for fun, would spread out until there was not an empty seat to be seen when he got on.

The target of their joke would stand between the two coaches, looking down each aisle. "Who'll let me have a seat to town for a dime?" he would bark. The others would suddenly be sleepy or immersed in the newspaper or engrossed in conversation.

The undaunted Mr. Stone would pound the floor with his umbrella. "Who'll let me have a seat for a quarter!" Again he would be ignored. Pounding again, he would shout a higher offer, "Fifty cents!" Someone then would get up leisurely, collect a half-dollar from Mr. Stone and surrender a seat.

There was another passenger who furnished us more covert amusement. This was a distinguished looking man in a well-tailored overcoat and derby hat. He lived in a big house on a hill and had little to do with the native Peweesers. Usually, he walked to the train, carrying a briefcase, with a folded newspaper under his arm.

In winter, when there was snow and ice, the notable-looking passenger would arrive on his son's sled, hauled by the yardman. With dignity he would get off, straighten up, put his paper under his arm, tip his hat to the yardman and board the train. Inside, he nodded to the few passengers he knew and buried himself in the paper. (Editor's note: This may have been Powhatan Wooldridge, who lived at The Locust and worked for Commonwealth Life Insurance from 1911 until his death in 1940. The Locust meets the "big house on a hill" description. Wooldridge also had a grandson who delivered newspapers throughout Pewee Valley and died of tubercular meningitis in 1915. He came from a wealthy family in Versailles and would have had little use for his neighbors, other than Darwin Johnston, a bigwig at Commonwealth, who summered in Pewee Valley.)

Then there was Miss Mamie, who worked in the office of the L&N president. She had the important job of keeping tab on all the railroad's coaches and assembling special trains. All up and down the line, officials high and low knew Miss Mamie for her work and for the flowers, fruits and vegetables she raised on the acres around her home in Pewee Valley.

When the jonquils bloomed she and her yardman, who was called Old Bus, would bring baskets full of these yellow flowers down to the station for friends in the L&N offices and elsewhere in the city. The station master, the fireman, Old Bus and any other men available would help load the jonquils on the train.

In summer, it was vegetables that she took to friends and in the fall, apples.

Miss Mamie had trouble keeping track of personal possessions. Often she called to the departing Old Bus to run home and bring her reading glasses off the bureau. Of course, the train had to wait until Old Bus returned. (Editor's note: Miss Mamie was Mamie Cleland, who lived at 117 Ashwood Avenue in what is known today as the Cleland House. She was an early -- and very successful -- businesswoman, and supported her mother and much-older stepsister and her husband for many years.)

The seats in the coaches were covered with stiff red plush. The backs were high and the padding was unyielding. The air in the cars was perennially acrid and smoky. It made your nostrils sooty. But we could reverse the stiff backs so that two couples could face each other and visit. Those tall backs also sheltered and shielded tender romances.

The conductor of the "Little Train" wore a serge suit with silver buttons. As he punched tickets and checked passes he had a greeting for each passenger. He made them all feel better by the interest he took in their joys, sorrows, romances and problems. When the train reached Louisville the passengers got off smiling.

The next train through Pewee was as handsome as the "Little Train" was homely. The "Pan American" clicked in and out of town at 11:15 a.m. en route from Cincinnati to New Orleans. It was new and shining and silver. If it was late, one subconsciously realized that something was wrong with the day.

Although the "Pan" didn't stop, it brought the mail from the East. It was fascinating to see the men in the baggage cars swing up the mail bags and hook them onto iron rings on a post in the station as the "Pan" rushed through. (Editor's note: Iris' description of mail delivery by train is wrong. The train actually pulled mail bags OFF the "post in the station," which was technically known as a mail crane. Read more about how it worked on the Mail By Rail page.)

The big event of the day in Pewee Valley was the return of the "Little Train" at 5:30 p.m. It was a social occasion; the children were in frilly dresses and starched suits; mothers looked fresh and lovely to meet husbands and greet friends. The women visited at the station until train time, and if the children grew bored, they could listen to the telegraph keys clicking off messages from trains as far off as New Orleans or Mobile.

With much ringing of bells and letting off of steam the "Little Train" chuffed into the station. Passengers got off, news was exchanged, the events of the journey were related. Then the "Little Train" was off to its last stop, at Eminence, to wait out the night.

Passengers called the 9:20 p.m. train the "Bed Time Train." It was No. 1, on its way to New Orleans. When we visited friends in the evening and heard the first blast of the whistle from No. 1, Dad would pull out his watch and check the time. Mother would say, "There's the 'Bed Time Train.' It's time we were going home."

When I began dating, the whistle of the "Bed Time Train" became the signal that my date should say goodnight. If he showed no sign of going, Mother came down and announced, "The 'Bed Time Train' has gone through.'"

Like the "Pan," No. 1 was a through train that didn't ordinarily stop at little towns. But exceptions could be made. After I had been away from my first year in college and returned home for the summer holidays, Miss Mamie pulled strings in the L&N headquarters and the "Bed Time Train" stopped in Pewee Valley to let me off.

I was very full of myself when the conductor who checked my ticket out of Cincinnati said, "So you're the young lady we're going to stop the train for in Pewee Valley." I probably blushed at such fame. He added solicitously, "I'll have the porter take your suitcase forward. You follow him. That way you can get right off at the station. This is a long train and the coach you're on now will stop way up the track."

After he moved on, I sat up and looked all around me to see how many people had heard him. Then I sat back and became aware of the fragrance of honeysuckle and Dorothy Parker roses that covered the banks of the train track. To this day the fragrance of honeysuckle brings memories of that homecoming.

Peweesers watched for and counted the special trains that brought the crowd to Louisville for the Kentucky Derby. They began to arrive the day before the race, often forcing the "Little Train" to wait on a siding. We who watched the special trains might not get to see the great race, but we felt like participants in the gaiety of the day. Today, with airlines and automobiles bringing the crowd into Louisville for the race and out the same day, some of the fun has gone.

As the number of scheduled trains began to drop, we felt regret. Whenever a train was discontinued it felt like losing a friend. The"Little Train" was our first and hardest loss. We got up a petition and wrote letters to the railroad, but to no avail, because the L&N office people, for whom it had been a convenience, had taken to driving their cars into the city.

And so the trains are gone. It seems to me they brought people together in friendship, in friendly argument, even in romance, as no other mode of travel ever can.

In winter, when there was snow and ice, the notable-looking passenger would arrive on his son's sled, hauled by the yardman. With dignity he would get off, straighten up, put his paper under his arm, tip his hat to the yardman and board the train. Inside, he nodded to the few passengers he knew and buried himself in the paper. (Editor's note: This may have been Powhatan Wooldridge, who lived at The Locust and worked for Commonwealth Life Insurance from 1911 until his death in 1940. The Locust meets the "big house on a hill" description. Wooldridge also had a grandson who delivered newspapers throughout Pewee Valley and died of tubercular meningitis in 1915. He came from a wealthy family in Versailles and would have had little use for his neighbors, other than Darwin Johnston, a bigwig at Commonwealth, who summered in Pewee Valley.)

Then there was Miss Mamie, who worked in the office of the L&N president. She had the important job of keeping tab on all the railroad's coaches and assembling special trains. All up and down the line, officials high and low knew Miss Mamie for her work and for the flowers, fruits and vegetables she raised on the acres around her home in Pewee Valley.

When the jonquils bloomed she and her yardman, who was called Old Bus, would bring baskets full of these yellow flowers down to the station for friends in the L&N offices and elsewhere in the city. The station master, the fireman, Old Bus and any other men available would help load the jonquils on the train.

In summer, it was vegetables that she took to friends and in the fall, apples.

Miss Mamie had trouble keeping track of personal possessions. Often she called to the departing Old Bus to run home and bring her reading glasses off the bureau. Of course, the train had to wait until Old Bus returned. (Editor's note: Miss Mamie was Mamie Cleland, who lived at 117 Ashwood Avenue in what is known today as the Cleland House. She was an early -- and very successful -- businesswoman, and supported her mother and much-older stepsister and her husband for many years.)

The seats in the coaches were covered with stiff red plush. The backs were high and the padding was unyielding. The air in the cars was perennially acrid and smoky. It made your nostrils sooty. But we could reverse the stiff backs so that two couples could face each other and visit. Those tall backs also sheltered and shielded tender romances.

The conductor of the "Little Train" wore a serge suit with silver buttons. As he punched tickets and checked passes he had a greeting for each passenger. He made them all feel better by the interest he took in their joys, sorrows, romances and problems. When the train reached Louisville the passengers got off smiling.

The next train through Pewee was as handsome as the "Little Train" was homely. The "Pan American" clicked in and out of town at 11:15 a.m. en route from Cincinnati to New Orleans. It was new and shining and silver. If it was late, one subconsciously realized that something was wrong with the day.

Although the "Pan" didn't stop, it brought the mail from the East. It was fascinating to see the men in the baggage cars swing up the mail bags and hook them onto iron rings on a post in the station as the "Pan" rushed through. (Editor's note: Iris' description of mail delivery by train is wrong. The train actually pulled mail bags OFF the "post in the station," which was technically known as a mail crane. Read more about how it worked on the Mail By Rail page.)

The big event of the day in Pewee Valley was the return of the "Little Train" at 5:30 p.m. It was a social occasion; the children were in frilly dresses and starched suits; mothers looked fresh and lovely to meet husbands and greet friends. The women visited at the station until train time, and if the children grew bored, they could listen to the telegraph keys clicking off messages from trains as far off as New Orleans or Mobile.

With much ringing of bells and letting off of steam the "Little Train" chuffed into the station. Passengers got off, news was exchanged, the events of the journey were related. Then the "Little Train" was off to its last stop, at Eminence, to wait out the night.

Passengers called the 9:20 p.m. train the "Bed Time Train." It was No. 1, on its way to New Orleans. When we visited friends in the evening and heard the first blast of the whistle from No. 1, Dad would pull out his watch and check the time. Mother would say, "There's the 'Bed Time Train.' It's time we were going home."

When I began dating, the whistle of the "Bed Time Train" became the signal that my date should say goodnight. If he showed no sign of going, Mother came down and announced, "The 'Bed Time Train' has gone through.'"

Like the "Pan," No. 1 was a through train that didn't ordinarily stop at little towns. But exceptions could be made. After I had been away from my first year in college and returned home for the summer holidays, Miss Mamie pulled strings in the L&N headquarters and the "Bed Time Train" stopped in Pewee Valley to let me off.

I was very full of myself when the conductor who checked my ticket out of Cincinnati said, "So you're the young lady we're going to stop the train for in Pewee Valley." I probably blushed at such fame. He added solicitously, "I'll have the porter take your suitcase forward. You follow him. That way you can get right off at the station. This is a long train and the coach you're on now will stop way up the track."

After he moved on, I sat up and looked all around me to see how many people had heard him. Then I sat back and became aware of the fragrance of honeysuckle and Dorothy Parker roses that covered the banks of the train track. To this day the fragrance of honeysuckle brings memories of that homecoming.

Peweesers watched for and counted the special trains that brought the crowd to Louisville for the Kentucky Derby. They began to arrive the day before the race, often forcing the "Little Train" to wait on a siding. We who watched the special trains might not get to see the great race, but we felt like participants in the gaiety of the day. Today, with airlines and automobiles bringing the crowd into Louisville for the race and out the same day, some of the fun has gone.

As the number of scheduled trains began to drop, we felt regret. Whenever a train was discontinued it felt like losing a friend. The"Little Train" was our first and hardest loss. We got up a petition and wrote letters to the railroad, but to no avail, because the L&N office people, for whom it had been a convenience, had taken to driving their cars into the city.

And so the trains are gone. It seems to me they brought people together in friendship, in friendly argument, even in romance, as no other mode of travel ever can.

Related Links