Artist Mary Gardner Johnston

(November 16, 1872 - July 16,1966)

Mary Gardner "Mayme" Johnston achieved some measure of renown as an artist, but is probably better known as the stepdaughter of "Little Colonel" author Annie Fellows Johnston and as a close friend of photographer Kate Matthews, who frequently used her as a model in her photographs.

Her parents, William Levi Johnston (February 5, 1847-February 8, 1892) and Hallie Eaves, were married on January 10, 1872. Mary was the oldest of their three children:

Her parents, William Levi Johnston (February 5, 1847-February 8, 1892) and Hallie Eaves, were married on January 10, 1872. Mary was the oldest of their three children:

- Mary Gardner Johnston (1872-1966)

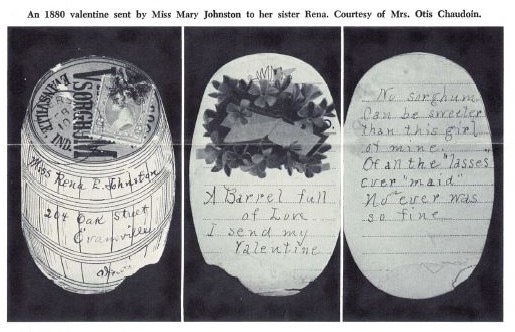

- Rena Johnston (1877-1899)

- John Eaves Johnston (1881-1910)

Family Background of William Levi Johnston

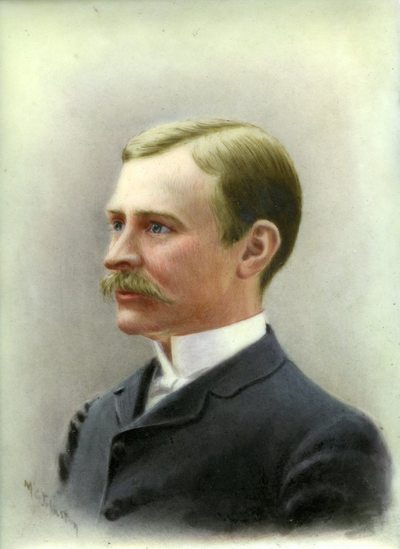

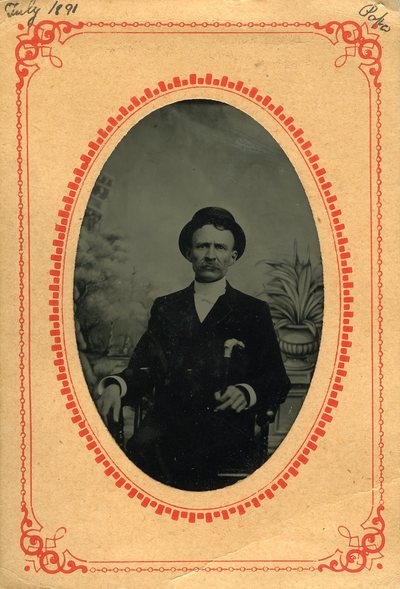

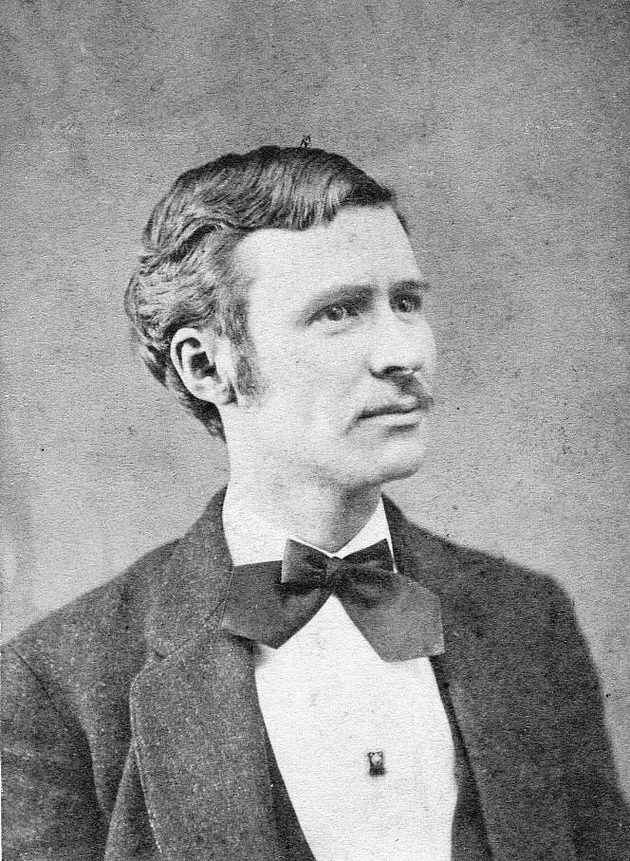

Photo of William Levi Johnston, courteay of the Albion Fellows Bacon-Annie Fellows Johnston Collection at the Willard Library, Evansville, Indiana

Photo of William Levi Johnston, courteay of the Albion Fellows Bacon-Annie Fellows Johnston Collection at the Willard Library, Evansville, Indiana

William Levi Johnston was a "manufacturing chemist" -- a.k.a. druggist -- and received his Bachelor's of Science degree from DePauw University's Asbury College of Liberal Arts in 1869. A brief sketch of his career is included in "Alumnal Record, DePauw University," edited by Martha J. Ridpath and published by the University in 1920:

313. William Levi Johnston

Manufacturing Chemist, Deceased

B.S. Born Feb. 5, 1847, Vanderburgh county, Ind. President of the Evansville Pharmaceutical Society, 1882-83; 1883-84. local secretary of the Indiana Pharmaceutical Association ; 1884, president of the Indiana Pharmaceutical Association ; 1885, secretary for Indiana of National Association for protection of game, birds and fish. Married, 1872, to Miss Hallie Eaves, who died August 4, 1883 ; married, 1888, to Miss Anna J. Fellows. Died, February 8, 1892, in Evansville, Indiana.

During the Civil War, he fought for the Union and was a "One Hundred Days" Volunteer, serving in Indiana's 136th Regiment, Company F. His regiment was mustered in in Indianapolis on May 25, 1864 and then immediately sent to Tennessee, where they guarded the Nashville & Chatanooga, Tennessee & Alabama, and Memphis & Charleston railroad lines.

313. William Levi Johnston

Manufacturing Chemist, Deceased

B.S. Born Feb. 5, 1847, Vanderburgh county, Ind. President of the Evansville Pharmaceutical Society, 1882-83; 1883-84. local secretary of the Indiana Pharmaceutical Association ; 1884, president of the Indiana Pharmaceutical Association ; 1885, secretary for Indiana of National Association for protection of game, birds and fish. Married, 1872, to Miss Hallie Eaves, who died August 4, 1883 ; married, 1888, to Miss Anna J. Fellows. Died, February 8, 1892, in Evansville, Indiana.

During the Civil War, he fought for the Union and was a "One Hundred Days" Volunteer, serving in Indiana's 136th Regiment, Company F. His regiment was mustered in in Indianapolis on May 25, 1864 and then immediately sent to Tennessee, where they guarded the Nashville & Chatanooga, Tennessee & Alabama, and Memphis & Charleston railroad lines.

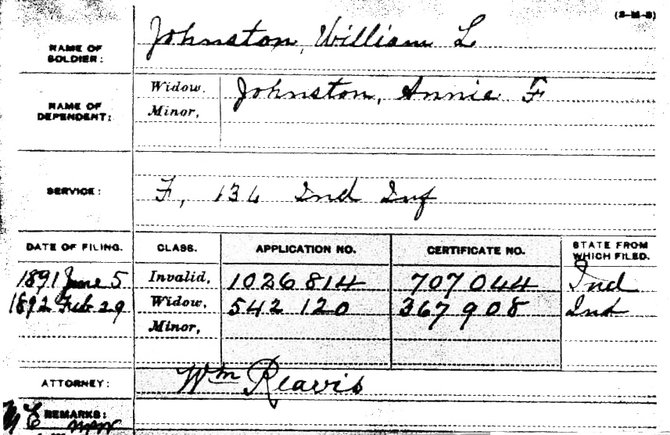

In 1891, William Levi Johnston applied for a pension for his Civil War service. Like his first wife, Hallie, he suffered from TB. After his death, his second wife, Annie Fellows Johnston, applied to receive the pension as his widow.

In 1891, William Levi Johnston applied for a pension for his Civil War service. Like his first wife, Hallie, he suffered from TB. After his death, his second wife, Annie Fellows Johnston, applied to receive the pension as his widow.

The "One Hundred Days" volunteers were the brainchild of Ohio Governor John Brough, who, after John Hunt Morgan's raid into Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio in 1863, wanted to prevent further Confederate incursions in the North. His goal was to raise 100,000 men to free veteran units for combat duty in the South and hasten the war's end. Brough contacted the governors of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin. They proposed the idea to the Lincoln administration and the plan was immediately approved. Altogether, some 81,000 men from these five states were recruited and became known as "Hundred Days Men."

The "One Hundred Days" volunteers were the brainchild of Ohio Governor John Brough, who, after John Hunt Morgan's raid into Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio in 1863, wanted to prevent further Confederate incursions in the North. His goal was to raise 100,000 men to free veteran units for combat duty in the South and hasten the war's end. Brough contacted the governors of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin. They proposed the idea to the Lincoln administration and the plan was immediately approved. Altogether, some 81,000 men from these five states were recruited and became known as "Hundred Days Men."

William Levi Johnston Portraits, From the Albion Fellows Bacon-Annie Fellows Johnston Collection at the Willard Library, Evansville, Indiana

Family Background of Hallie Eaves Johnston

Hallie was the second youngest child -- and the older of two daughters -- born to John S. Eaves (1813-1872) and Hannah Turbeville Eaves (1814-1854):

Eight years after her mother Hannah's death in 1854, Hallie's father remarried. On September 23, 1862, he tied the knot with Fannie Belt.

Hallie's father was a prosperous McLean County farmer and likely raised tobacco. The 1870 census valued his property at $25,000. In addition to his second wife Fannie and daughters Hallie and Rena, John had an African-American cook, Susan Crow, and her 12-year-old son, Lewis, residing in his home, along with a schoolteacher named Jennie Geddings.

- James T. Eaves (1834-?)

- George Washington Eaves (February 5, 1840-September 21, 1915)

- E.R. Eaves (1841-?)

- William A. Eaves (1846-?)

- Hallie (1849-August 4, 1883), married in 1872 to William Levi Johnston.

- Rena (1852 -April 22, 1898), named for her grandmother Lurena Ingram Eaves. She married Louisville tobacconist Albert W. Burge on August 16, 1870 and moved to Louisville, and later Pewee Valley, where she lived in the home that eventually became Mount Mercy Camp & Boarding School.

Eight years after her mother Hannah's death in 1854, Hallie's father remarried. On September 23, 1862, he tied the knot with Fannie Belt.

Hallie's father was a prosperous McLean County farmer and likely raised tobacco. The 1870 census valued his property at $25,000. In addition to his second wife Fannie and daughters Hallie and Rena, John had an African-American cook, Susan Crow, and her 12-year-old son, Lewis, residing in his home, along with a schoolteacher named Jennie Geddings.

George Washington Eaves, Hallie's brother and Mary's uncle, married Sarah Jane "Sallie" McNary on October 27, 1864, and they had several children:

- John Hughes Eaves (September 10, 1865-October 17, 1933)

- Lynn Eaves

- St. Clair "S. C." Eaves (1875–1942)

- Mattie F. Eaves (1878-?)

- Sarah G. Eaves (1880-1947)

- Hallie N. Eaves (1884-?)

|

|

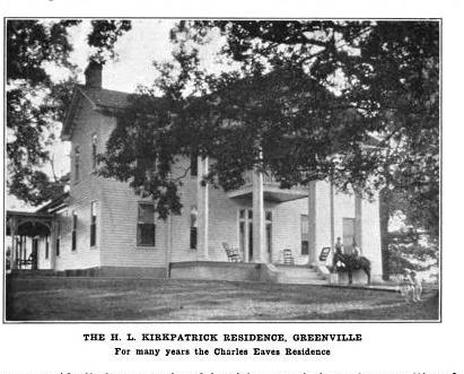

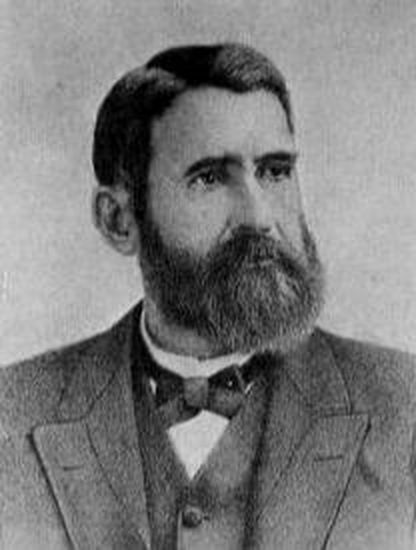

The Eaves family was well-respected in McLean County. A profile of Hallie's uncle, Charles Eaves, was included in the 1887 "Kentucky: A History of the State" Volume 2, by W.H. Perrin, J.H. Battle and G.C. Griffin:

CHARLES EAVES was born January 20, 1825, at his father's home, nine miles west of Greenville, Ky. His father was John S. Eaves, who was born in Virginia, in 1783; removed to Kentucky in 1805; was a farmer; a man of sterling integrity, thrifty, intelligent, sagacious; serving his county as justice of the peace, as sheriff and twice as representative in the legislature; dying at the age of eighty-five, honored and respected by all who knew him. His mother, Lurena Eaves, nee Ingram, was remarkable for domesticity and admirable household ways; for hospitality dispensed without ostentation, yet with a heartsome welcome, so that no one ever visited the house who did not wish to repeat or prolong the visit. Charles, the subject of this sketch, the youngest of five sons (he had three sisters), was educated chiefly at home. In early boyhood he became a voracious reader. He gathered books and spun his own web of knowledge. On his father's farm, his habit was to read half the night, after working on the farm all day. At the age of eighteen, he took up the study of law on the farm, reading Blackstone, Kent, Story, Chitty, Steven, Starkie, Greenleaf, and numerous other text books, and, after three years' reading, obtained license to practice law. He was admitted to the Greenville bar in September, 1846. Since then he has devoted his life to the study and practice of the law, and to a pretty thorough study of literature. He is now a ripe, thorough lawyer, ranking high in his profession. His knowledge is encyclopedic. As a pleader, he is skillful, accurate, thorough; as a speaker, never rhetorical, but plain, direct, compact and clear; always fair and honorable in the conduct of a case, and generally successful. If eloquence he has, it is the eloquence of conviction and clearness. He wins his cases by careful preparation, clearness of statement and fairness of argument. He served his county (Muhlenburg) one year as county attorney; one year as school commissioner, and one term as representative in the legislature. In 1865, he removed to Henderson, Ky., and after a residence there of twelve years, returned to Greenville, where he |

now resides in his quiet tree-embowered suburban home. At Henderson he was city attorney for three years. The office was unsought, and he held it until he resigned. From having frequently presided as special judge in the circuit courts, he is generally known as Judge Eaves. Not old at sixty; six feet high, and, though not obese, weighing 200 pounds, healthy and strong, with a memory like a chronicle, with a love of books unabated--opening a book with a swift glance whether it has a message for him--reading a new law book with as much zest as a novel, drinking its meaning up as a sponge absorbs water--Judge Eaves is likely to survive the present century as an active member of his profession, honored and respected by the bench and the bar, as well as by the people, and after his death, his ghost may possibly be seen by his confreres about the purlieus of the courts, with a law book or a bundle of papers under its arm. Judge Eaves married, March 24, 1852, at Greenville, Ky., Miss Martha G. Beach, daughter of Rufus and Rhoda Beach, who was born at Rochester, N. Y. Her maternal grandmother, whose maiden name was Olive Ann Stoddard, was a descendant of Anthony Stoddard, who came to Massachusetts Colony from England in 1638, among whose descendents--President Edwards and his grandson, Aaron Burr, of a generation passed away, and Gen. W. T. Sherman and John Sherman of the present day, may be named. Judge Eaves and his wife are members of the Protestant Episcopal Church. They have four children. Judge Eaves is a member of the I. O. O. F.

Early Childhood

|

|

In 1880, seven-year-old Mary was living with her parents at 813 Second Street in Evansville, Ind. Her father was working as a druggist and her younger sister, Rena, was two years old. In 1881, her little brother John was born. At some point, her mother contracted tuberculosis. She was too sick to care for the children by 1882 and died of consumption on August 4, 1883.

Mary's father did what many men did during that era; he sent his children to be raised by a female relative -- Hallie's sister Rena and his brother-in-law Albert W. Burge in Pewee Valley. Mary's obituary stated she was 10 years old when she moved to Pewee Valley, making Rena about 5 and John just a year old. The three Johnston children spent the next five years living with their aunt, uncle and cousin, Hallie, at Delacoosha, the Burges' stately Pewee Valley home. There they were exposed to a glamorous lifestyle of live-in servants, carriage rides, parties, lawn tennis, debutantes and society weddings. At that time, Pewee Valley was at the height of its popularity as a summer playground for Louisville's elite. And the Burges had plenty of wealthy friends and relations in Louisville, as well. On October 27, 1885, Mary was part of the bridal party for her Aunt Sarah Lloyd Burge's wedding to Sidney Smith Muir, son of Judge Peter B. Muir. The wedding took place at the new "Millionaire's Row" home of Albert Burge's brother-in-law, lawyer Sterling B. Toney on Third Street in Louisville. Toney had |

married Albert's sister, Emma, in 1876. A newspaper clipping describing the wedding (date and paper unknown, from the Dick Family Collection) noted:

... Eichhorn's orchestra furnished the music, and instead of the Wedding March, played "Call Me Thine Own," as the bridal party entered.

First came two little girls, nieces of the bride, Hallie Louise Burge and Mary Johnston, one in blue and the other in pink tarleton, strewing flowers in the way...

... Eichhorn's orchestra furnished the music, and instead of the Wedding March, played "Call Me Thine Own," as the bridal party entered.

First came two little girls, nieces of the bride, Hallie Louise Burge and Mary Johnston, one in blue and the other in pink tarleton, strewing flowers in the way...

Mary Johnston as a young woman

Mary Johnston as a young woman

Cousins Hallie and Mary were just a year apart in age. Hallie was born October 22, 1871. Mary was born on November 17, 1872. The girls remained close the rest of their lives. Reminiscences of Hallie Burge Jacob, included in a September 11, 1943 “Courier-Journal” article by Hamilton Howard, enumerated some of the pleasant distractions life in the Valley afforded young women, in addition to picnics, barn dances and teas:

... Life was different in Pewee those days... They would drive around to parties and entertainments all the time. We used to have house parties. Five or six men and girls came out on Saturday and stayed over Sunday. Buggy rides were a big event, but Momma didn't allow me to go on buggy rides-- just in carriages. I drove ten miles to a party in a horse break one time-- you wouldn't remember them. They were little narrow carriages with no back. My feet swung back and forth the whole way." ....

... Life was different in Pewee those days... They would drive around to parties and entertainments all the time. We used to have house parties. Five or six men and girls came out on Saturday and stayed over Sunday. Buggy rides were a big event, but Momma didn't allow me to go on buggy rides-- just in carriages. I drove ten miles to a party in a horse break one time-- you wouldn't remember them. They were little narrow carriages with no back. My feet swung back and forth the whole way." ....

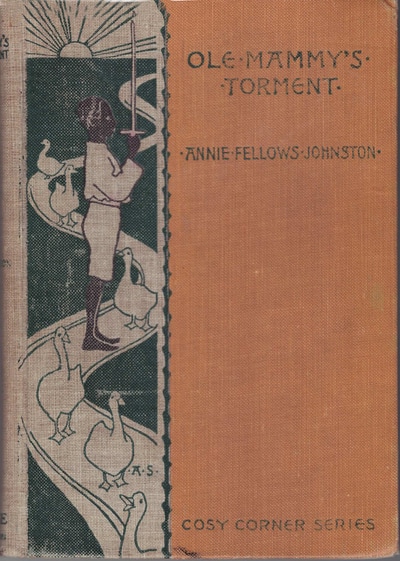

Delacoosha, the Burge's stately home in Pewee Valley, is where the Johnston children lived for five years. Annie Fellows Johnston later used the house in her 1897 novel "Ole Mammy's Torment:" "...one could see the red gables of the old Chadwick house, rising above the dark pine-trees that surrounded it. A wealthy city family by the name of Haven owned it now. It was open only during the summer months. The roses ... climbed all over the front of the house, twining around its tall pillars, and hanging down in festoons from its stately eaves. Cuttings from the same hardy plant had been trained along the fences, around the tree-trunks and over trellises, until the place had come to be known all around the country as 'Rosehaven.'"

Rena Eaves Burge, Mary's Aunt, Courtesy of Descendent Mark Holley

William Johnston's Second Marriage to Annie Fellows

Annie Fellows Johnston at age 16. From "History & Families of Oldham County: 1824-1924" published by the Oldham County Historical Society in 1996 (Turner Publishing, Paducah, Ky.)

Annie Fellows Johnston at age 16. From "History & Families of Oldham County: 1824-1924" published by the Oldham County Historical Society in 1996 (Turner Publishing, Paducah, Ky.)

On August 11, 1888, Mary's father remarried, this time to Annie Julia Fellows, who was 16 years younger and had been working as a schoolteacher in Evansville. The newlyweds set up housekeeping at 204 Oak Street in Evansville and the children were soon reunited with their father and new stepmother. By then, Mary was 15, Rena 11, and John 9. However, Mary and Rena continued to visit the Burges in Pewee Valley every summer.

The marriage may have started out happily enough, but William was soon an invalid. Like his first wife, he suffered from consumption. He applied for a Civil War pension due to disability on June 5, 1891. Within eight months, TB had taken his life. He died on February 8, 1892. It was the second of four family tragedies that would strike Mary Johnston during her lifetime.

On February 29, 1892, a few weeks after his death, Annie applied for William's Civil War pension as his widow, but family finances were grim. She turned to writing and published her first book, "Big Brother," in 1893. According to According to “The Genealogical History of The McGaffey Family, Including also the Fellows, Ethridge and Sherman Families,” published by George W. McGaffey in 1904, Annie Fellows Johnston managed to hold onto the family home on Oak Street in Evansville for five years and her stepchildren “...were as dear to her as though they had been her own.” However, by 1897, economic necessity forced the author to break up their Evansville home and travel, according to her autobiography, “The Land of the Little Colonel:”

In September, 1897, we came to a turn in the road where we could see only one step ahead at a time. Rena joined Mary in Pewee Valley; I sold or stored our household goods and took John up to Highland Park to put him in the military school there.

Life with Her Stepmother

|

|

After Annie returned from a European tour, during which she worked as a travelling companion/governess/

chaperone for a young lady, the family lived for awhile with the Burges. There at Delacoosha she wrote “The Gate of the Giant Scissors" based on her travels. In 1898, they moved to The Gables nearby, possibly in the wake of Rena Eave Burge’s death after a lingering battle with kidney disease on April 22nd of that year. Tragedy struck again in September 1899, when Mary’s 21-year-old younger sister, Rena, “was taken very ill on the sixth with appendicitis. She died on the twelfth after an operation. Her death made us all the more anxious about John's health,” Annie wrote in her autobiography. By the time Rena died, Mary's little brother John, now 18, was suffering from consumption, the disease that killed both his parents. On the advice of physicians, Annie went on the road again in search of a healthier climate for her stepson. They spent the next few years travelling to Walton, New York; Lee's ranch in Arizona, where TB patients lived in tents to take advantage of the arid climate; California, where she presumably visited her friend, Mamie Lawton, who owned a home in Redlands near San Bernardino; and then to Comfort, Texas, another southwestern community near San Antonio that catered to "lungers." Mary remained in Pewee Valley much of the time. For her, Pewee Valley was home. |

Pen Acres at 609 E. Theissen Street was the Johnston home in Boerne, Texas, from 1905 to 1911. Photo taken 1949 for the San Antonio Evening News

Pen Acres at 609 E. Theissen Street was the Johnston home in Boerne, Texas, from 1905 to 1911. Photo taken 1949 for the San Antonio Evening News

John and Annie ended their wanderings in Boerne, Texas where in 1905, Annie bought a home she called Pen Acres. While visiting Indianapolis, Annie was interviewed by the Indianapolis News for an April 9, 1909 story. During the interview, she explained how she settled on the name:

"... Down in Texas I live in a bungalow and we called the place Pen Acres. I thought if Kate Douglas Wiggin called her home Quillcote, I should call mine Pen Acres."

Mary visited sporadically, according to a letter written September 23, 1908 by Annie to her friend Lilly:

Mamie went back to Kentucky in May to escape the heat. She is as much of an invalid now as John -- although not from the same cause. She stayed with Hallie till July, then went to Providence, R. I. to spend three weeks with Mrs. Bliss. -- (General Bliss's widow, who has her winter home in Boerne and is one of the most charming old ladies I ever knew). Then she went back to Pewee.

Despite the brutal summer heat, life in Boerne may have become more attractive to Mary after her cousin Hallie married architect Donald Jacob and moved to San Antonio. According to the same letter:

...The first of September Hallie and her husband moved to San Antonio, where he had a fine offer to go into partnership with one of its leading architects. They have taken a house there and Mr. Burge, the dogs and servants will follow soon...

"... Down in Texas I live in a bungalow and we called the place Pen Acres. I thought if Kate Douglas Wiggin called her home Quillcote, I should call mine Pen Acres."

Mary visited sporadically, according to a letter written September 23, 1908 by Annie to her friend Lilly:

Mamie went back to Kentucky in May to escape the heat. She is as much of an invalid now as John -- although not from the same cause. She stayed with Hallie till July, then went to Providence, R. I. to spend three weeks with Mrs. Bliss. -- (General Bliss's widow, who has her winter home in Boerne and is one of the most charming old ladies I ever knew). Then she went back to Pewee.

Despite the brutal summer heat, life in Boerne may have become more attractive to Mary after her cousin Hallie married architect Donald Jacob and moved to San Antonio. According to the same letter:

...The first of September Hallie and her husband moved to San Antonio, where he had a fine offer to go into partnership with one of its leading architects. They have taken a house there and Mr. Burge, the dogs and servants will follow soon...

Boerne was just 31 miles away and railroad service between the two towns had been available since 1887. The service, however, was a far cry from the one-hour trip to Louisville the interurban offered residents of Pewee Valley. In her 1910 novel "Mary Ware in Texas," Annie described the morning train ride as taking four hours, with stops at the Lime Works, the Rock Quarry and the "Government Reservation"(Editor's note: the Leon Springs Military Reservation twenty miles northwest of San Antonio).

On April 26, 1910, Mary's brother lost his ten-year battle with TB -- the fourth family tragedy in Mary's life. John Johnston's obituary ran in the San Antonio Light and Gazette the next day:

JOHNSTON—Word was received in the city on Monday night announcing the death at Boerne of John Johnston, 29 years old. He is survived by his mother, Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, a noted author, who came to San Antonio eight years ago with her son from Kentucky in the hopes that the change of climate might restore his health. Following a short residence here, the mother and son took up their residence in Boerne. He is also survived by a sister, Miss Mary Johnston, and a cousin Mrs. D.R. Jacob of San Antonio....

On April 26, 1910, Mary's brother lost his ten-year battle with TB -- the fourth family tragedy in Mary's life. John Johnston's obituary ran in the San Antonio Light and Gazette the next day:

JOHNSTON—Word was received in the city on Monday night announcing the death at Boerne of John Johnston, 29 years old. He is survived by his mother, Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, a noted author, who came to San Antonio eight years ago with her son from Kentucky in the hopes that the change of climate might restore his health. Following a short residence here, the mother and son took up their residence in Boerne. He is also survived by a sister, Miss Mary Johnston, and a cousin Mrs. D.R. Jacob of San Antonio....

After his death, Mary persuaded her stepmother to leave Boerne, where Annie had made many friends, and return to Pewee Valley -- Mary Johnston's "Promised Land" -- and Mary Ware's, too, in the final volume of the "Little Colonel" stories. In 1911, Annie sold Pen Acres to J.W. Lawhon and purchased The Beeches from Mamie Lawton. Their move back to Kentucky was noted in the April 9, 1911 Galveston Daily News:

Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston and her daughter left for their new home in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, Friday (editor's note: April 7, 1911)

Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston and her daughter left for their new home in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, Friday (editor's note: April 7, 1911)

Friendship with Kate Matthews

Kate Matthews photo of Mary Johnston clutching a handful of oak leaves. Courtesy of Richard Duncan, Jr.

Kate Matthews photo of Mary Johnston clutching a handful of oak leaves. Courtesy of Richard Duncan, Jr.

Mary -- usually referred to as "Miss Mayme" by her neighbors -- had many friends in Pewee Valley, including photographer Kate Matthews. Her association with Kate may have sprung from their mutual interest in art. As Annie Fellows Johnston wrote in “The Little Colonel at Boarding School,” Katie Marks – for whom Kate Matthews served as prototype -- only allowed those with “artist souls” admittance to her photography studio at Clovercroft -- and Mary Johnston was certainly among that elite. According to a Valley Vignette written by Florence Dickerson for the July 1974 Call of the Pewee, Mary and her stepmother often stayed at Clovercroft while visiting Pewee Valley in the years before they moved to The Beeches.

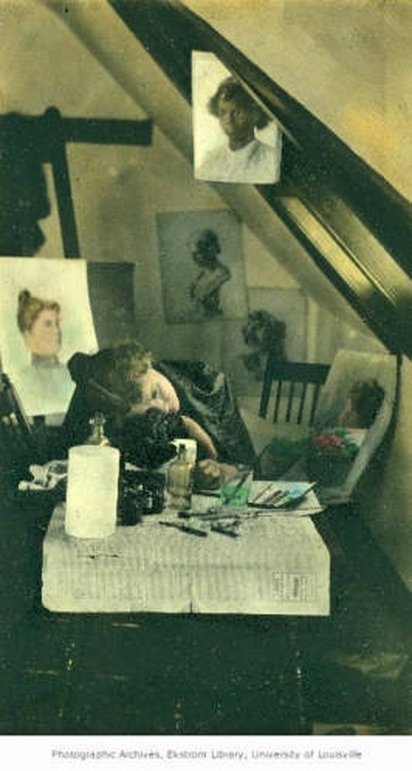

The pair were a common sight in Pewee Valley’s fields and gardens -- Miss Kate with her camera and Miss Mamie with her paints. Mamie was one of Kate’s favorite models. Included in the Kate Matthews Collection at the University of Louisville’s Ekstrom Library are many photos of Miss Mamie posing as herself as well as various characters, such as Tennyson’s Elaine, a winged angel and a nun. Kate’s pictures of Mary have an ethereal quality not seen in some of her other compositions.

The two women also got into their share of mischief, as Kate recounted in a November 29, 1942 “Courier-Journal” story called “These Pictures Will Take You Back” by Bunch Brady:

... Many times Kate and Mamie Johnston used to climb through a window in the condemned Episcopal Church building and dress up in the choir’s vestments ...

The pair were a common sight in Pewee Valley’s fields and gardens -- Miss Kate with her camera and Miss Mamie with her paints. Mamie was one of Kate’s favorite models. Included in the Kate Matthews Collection at the University of Louisville’s Ekstrom Library are many photos of Miss Mamie posing as herself as well as various characters, such as Tennyson’s Elaine, a winged angel and a nun. Kate’s pictures of Mary have an ethereal quality not seen in some of her other compositions.

The two women also got into their share of mischief, as Kate recounted in a November 29, 1942 “Courier-Journal” story called “These Pictures Will Take You Back” by Bunch Brady:

... Many times Kate and Mamie Johnston used to climb through a window in the condemned Episcopal Church building and dress up in the choir’s vestments ...

Career as an Artist

|

|

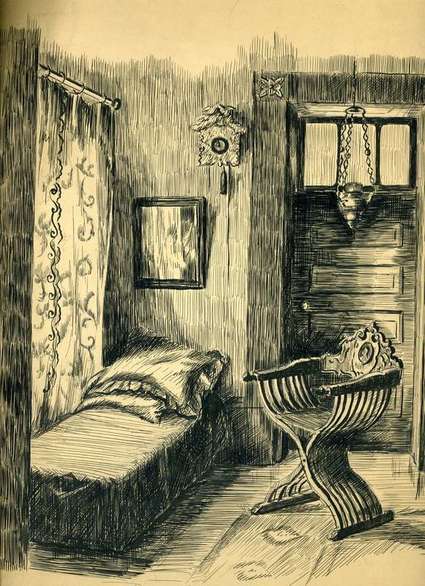

Like her stepmother's career as a writer, Mary Johnston’s career as an artist began as a matter of economic necessity. Cary Hoge Mead’s autobiography, “Sunshine and Shadows,” relates how Miss Mamie helped support the family early in Annie’s career as a writer:

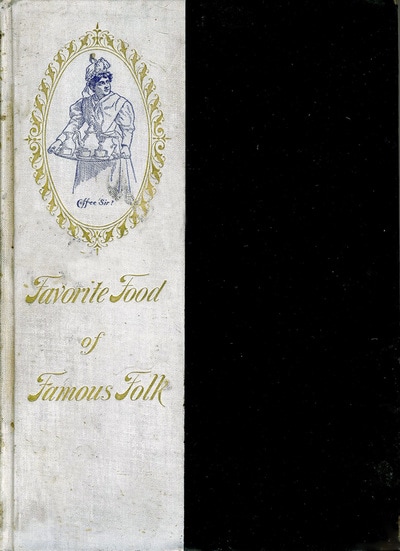

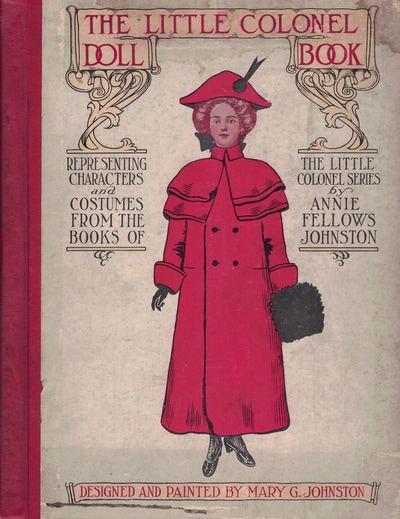

…Annie Fellows had married Mr. Johnston, who was a widower with three children -- Mamie, aged 15, Rena, aged 10, and John, aged five, who adored Mrs. Johnston and was as close as an own son. In fact, they all were, for Mrs. Johnston had the key which unlocked all hearts, especially children and young people. The children's mother had died when John was quite little, and they welcomed this God-given mother with their whole hearts. After only two years of happiness, Mr. Johnston was taken ill, and after three years of invalidism, during which the family's financial resources were used up, he died. This left Mrs. Johnston with three rather delicate dependents and no money. However, Mamie was a gifted artist and helped out by selling some of her paintings while Mrs. Johnston was becoming established as an author. Mamie helped illustrate one of her stepmother’s early books, “Ole Mammy’s Torment,” published in 1897. Years later, she illustrated “The Little Colonel's Doll Book” published in 1910. Several sources credit her with illustrating the first book and others credit her with illustrating all the books in the Little Colonel series; however, the L.C. Page and Co., which became her stepmother's primary publisher, used Etheldred Barry to illustrate most of the first editions. In 1901, she helped hand-illuminate a limited edition version of the St. James Episcopal Church's fundraising cookbook, "Favorite Food of Famous Folk." A story detailing her work on the cookbook and "Ole Mammy's Torment" appeared in the February 9, 1901 Courier-Journal: The little church of St. James, Pewee Valley, has immortalized itself by compiling one of the most unique volumes ever published. "Favorite Food of Famous Folk" was so enthusiastically received by an admiring public that it is to be regretted that only a favored few can have access to the second edition. It is limited to one hundred copies. It is hand-illumed and illustrated by Miss Mary Gardner Johnson, of Pewee Valley, and Miss B. Cook Stoy, of Louisville... ... Miss Johnston, who is doing one-half the edition, is the daughter of Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, the writer of juvenile books. Miss Johnston illustrated one of her books, "Old (sic) Mammy's Torment." Hers is the illustration of St. James in that book. The toll gate was sketched near Pewee Valley, and the original of "Marse Nat Chadwick" lives at Floydsburg, a little way up the pike. |

Books Illustrated by Mary Gardner Johnston

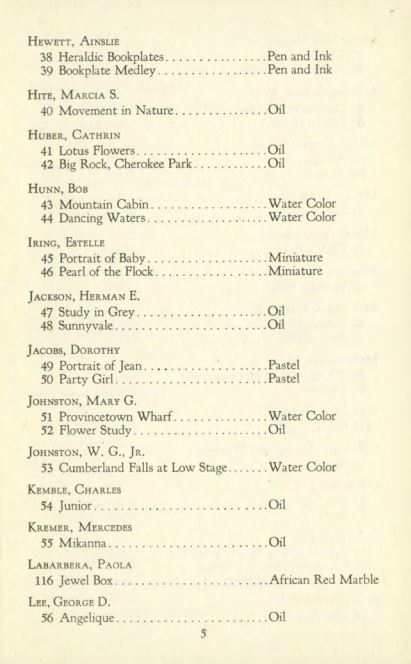

Page from the J.B. Speed Memorial Museum Exhibition Catalog, October 1-31, 1933

Page from the J.B. Speed Memorial Museum Exhibition Catalog, October 1-31, 1933

Her work on the "Little Colonel Doll Book" blended photography with art. Kate Matthews photographed the models for the characters and Mary designed and painted the costumes. In total, she painted 48 color plates.

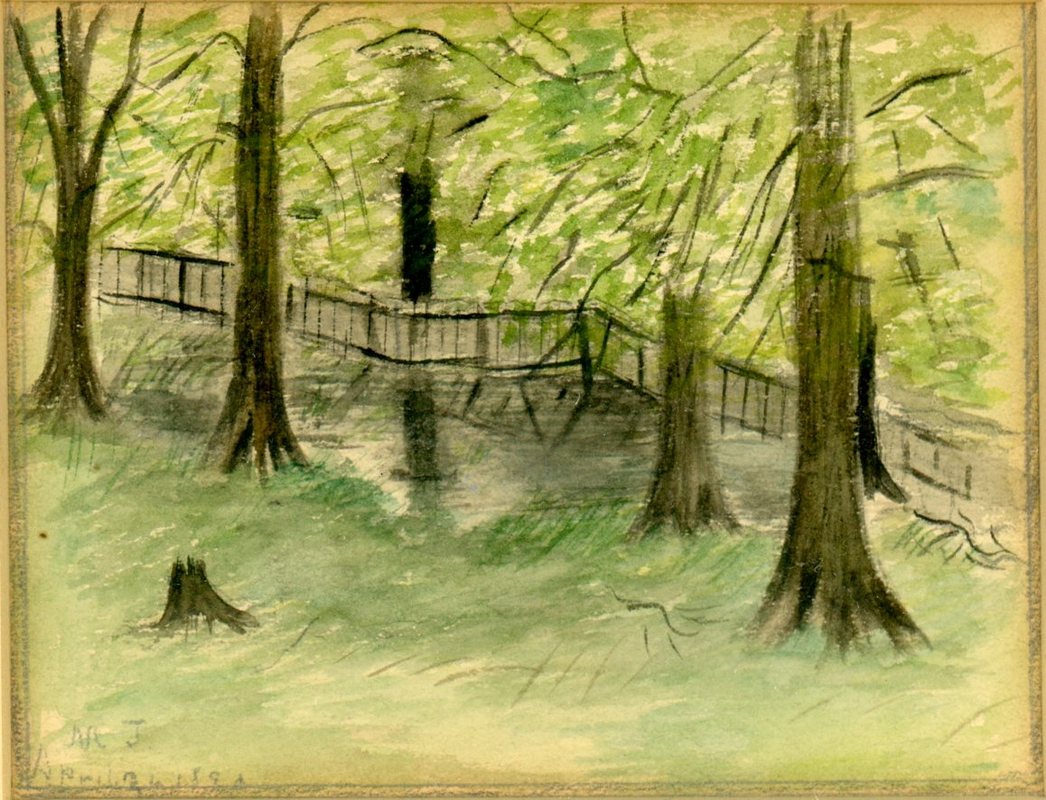

While living at The Beeches from 1911 until her death in 1966, Mamie kept her art studio in a small room tucked under the eaves on the third floor. She worked in a variety of media, including pencil, oils and watercolors. Her paintings were primarily portraits, still lifes and landscapes, although she did paint several homes in Pewee Valley.

In 1933, two of Mary Johnston's works were displayed at a "NO-JURY Exposition of Fine and Practical Arts by Louisville Artists" at the J.B. Speed Art Museum : a watercolor of Provincetown wharf and a flower study in oil. Some 76 Louisvillians exhibited their work from October 1-31 that year.

The Speed later acquired two of her paintings: "Ernest" and "Tarascon Indian." In 1990, "Tarascon Indian" -- described by the Diane Heilenmen as "pleasantly gutsy" in the June 1990 Courier-Journal -- was exhibited during the Speed's show on "Women in Art: Kentucky's Women Artists."

At some point in her career, Mary studied at the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts. She may have learned about the school or attended it while visiting Mrs. Bliss in Provincetown in 1908.

Opened in 1899 by impressionist Charles Hawthorne, the Cape Cod School of Art was the first school to teach outdoor figure painting. Hawthorne used Provincetown's waterfront during the summer to teach his plein air method. Models were posed in bright sunlight and their faces were shaded by hats or parasols, rendering their features invisible. By 1915, it had grown into one of the largest art colonies in the world, with as many as 90 students from across the U.S. enrolled in a session. The school's weekly outdoor demonstrations attracted crowds. Among the artists who studied there and went on to achieve fame were Emile Gruppe, Norman Rockwell, Max Bohme and Richard Miller. The watercolor of Provincetown's wharf Mary exhibited at the Speed Museum was probably completed during her studies at the school.

While living at The Beeches from 1911 until her death in 1966, Mamie kept her art studio in a small room tucked under the eaves on the third floor. She worked in a variety of media, including pencil, oils and watercolors. Her paintings were primarily portraits, still lifes and landscapes, although she did paint several homes in Pewee Valley.

In 1933, two of Mary Johnston's works were displayed at a "NO-JURY Exposition of Fine and Practical Arts by Louisville Artists" at the J.B. Speed Art Museum : a watercolor of Provincetown wharf and a flower study in oil. Some 76 Louisvillians exhibited their work from October 1-31 that year.

The Speed later acquired two of her paintings: "Ernest" and "Tarascon Indian." In 1990, "Tarascon Indian" -- described by the Diane Heilenmen as "pleasantly gutsy" in the June 1990 Courier-Journal -- was exhibited during the Speed's show on "Women in Art: Kentucky's Women Artists."

At some point in her career, Mary studied at the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts. She may have learned about the school or attended it while visiting Mrs. Bliss in Provincetown in 1908.

Opened in 1899 by impressionist Charles Hawthorne, the Cape Cod School of Art was the first school to teach outdoor figure painting. Hawthorne used Provincetown's waterfront during the summer to teach his plein air method. Models were posed in bright sunlight and their faces were shaded by hats or parasols, rendering their features invisible. By 1915, it had grown into one of the largest art colonies in the world, with as many as 90 students from across the U.S. enrolled in a session. The school's weekly outdoor demonstrations attracted crowds. Among the artists who studied there and went on to achieve fame were Emile Gruppe, Norman Rockwell, Max Bohme and Richard Miller. The watercolor of Provincetown's wharf Mary exhibited at the Speed Museum was probably completed during her studies at the school.

Keeping Annie Fellows Johnston's Legacy Alive

|

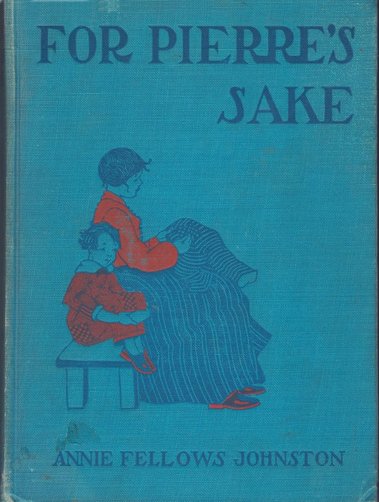

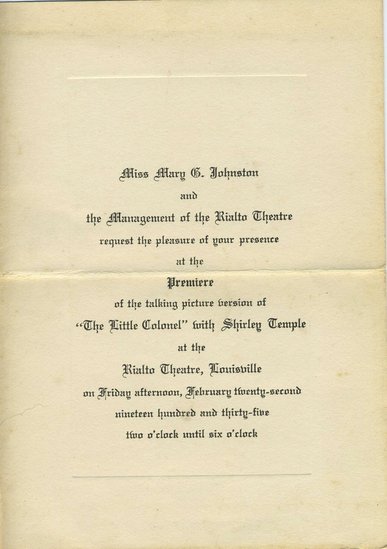

After Annie Fellows Johnston's death in 1931, Mary worked hard to keep her stepmother's legacy alive. Over the next 35 years, she met several times with reporters from local and Indiana papers, whenever they wanted to take a look back at Annie Fellows Johnston and her "Little Colonel" stories. She kept The Beeches as a shrine and welcomed the many tourists who came to see the Land of the Little Colonel in real life. She kept all the copyrights on Annie's "Little Colonel" novels current and allowed the posthumous publication of "For Pierre's Sake" in 1934, a compilation of short stories that were in the works when her stepmother died. She sold Fox the movie rights to the first "Little Colonel" story and, as part of the contract, put together a scrapbook of photographs showing the real people and places in Pewee Valley that inspired the book. The studio used it for costume and set design. On February 22, 1935, she hosted a premiere party for the Shirley Temple film at Louisville's Rialto Theatre and was also invited to the movie's New York premiere at Radio City Music Hall. In 1949, Mary briefly returned to Boerne for the town's Centennial celebration. She was invited because her stepmother's 1907 novel, "Mary Ware in Texas," provided such a vivid and accurate depiction of the town at the turn of the century. Also on the dignitary list was the newly-elected Governor of Texas Allen Shivers. The four-day event began the evening of Thursday, August 25 and ran through Sunday, August 28. Among the festivities were parades, Boerne White Sox baseball games, horse racing and exhibitions, a Queen's Ball, square dancing, a Fiesta Dance, |

and a children's carnival. A new children's book called "The Little Deputy" -- written, illustrated and printed by husband-wife team Fritz and Emilie Toepperwein -- debuted on Friday. But the main attraction was a live production of the town's history called "Cavalcade of Boerne." Scores of local citizens were involved in the extravaganza, which featured elaborate backdrops and some 250 costumes, including 30 shipped in from Hollywood.

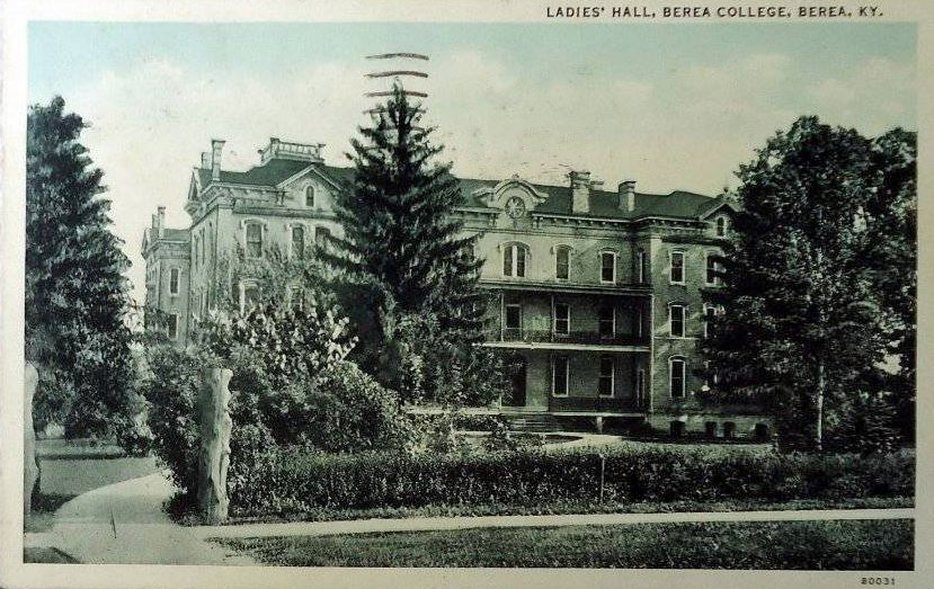

In 1954, Mary donated the manuscript of Annie's last, unfinished novel, "A Mountain Mailbag," to Berea College. The July 27, 1954 Courier-Journal described how the gift came about:

Dr. William J. Frost handed the presidency of Berea College over to Dr. William J. Hutchins in 1920, and when he died he left all his papers to the college.

This year Dr. Elizabeth Peck of the history department, who has been at Berea College "man and boy" since 1912, was made college historian. She immediately undertook to go through those papers.

To her great excitement, being a "Little Colonel" fan, she found two letters from Annie Fellows Johnston, dated 1919 and 1920, in which the author wrote:

"I am very busy with a work I hope to be of profit to Berea, indirectly. It is a book about the mountain people themselves, putting their various problems into a story which I hope will have as wide an influence as my other books seem to have exerted. It is to be called 'A Mountain Mailbag" ... D. Appleton and Company, who will publish the book, are quite enthusiastic."

"How strange," thought Dr. Peck, "that I have never read the book." There was no copy in the college library. And when she wrote the Louisville Free Public Library staff, they reported that not only was the book not in the library, but they could find no record of its publication. Dr. Peck was nonplussed -- but not for long.

She knew Mrs. Johnston had lived with a daughter, Miss Mary Johnston, at Pewee Valley, so she wrote to ask her: "Where is the book?"

The letter, when it arrived at Miss Johnston's home, The Beeches, created great interest. For Miss Johnston had had the original manuscript ever since the beginning of the author's long illness in 1920. It had rested there in Pewee Valley all this time in its original briefcase.

Miss Johnston immediately sent the first two chapters to Dr. Peck, asking her to go over them, explaining that the briefcase contained parts of 16 chapters and a heading for a 17th -- some quite complete, some fragmentary, some only in summary. They were in typescript with notes in Annie Fellows Johnston's handwriting.

Berea wrote back that they wished they might own the manuscript, but could not afford to buy it, and did not know whether in its incomplete state anyone would publish it. But they asked if they might have it on loan for display, especially in the centennial year, so that the thousands of tourists who would come to see Paul Green's festival drama, "The Wilderness Trail," might get still another glimpse of Berea's nostalgic past.

Mary Johnston said she would be delighted to give the manuscript to Berea. She has been wondering for years what she ought to do with it to make it accessible for she knew that interest in Mrs. Johnston's work had never waned. In fact, only last year the 53rd printing of a collection of "Little Colonel" stories was issued.

The theme of the story is unequivocally stated in Chapter 10: the struggles between those people in the mountains, mostly the young, who wanted an education, and those who for various reasons were afraid of it...

... Mrs. Johnston has copied and put together from the author's diary of 1919-1920 some of the relevant notes about her visits to Berea and her trips to the neighboring hills...

... The three who drove from Berea for formal presentation of the manuscript -- Dr. Peck, Miss Charlotte Stephens, who is Dr. Hutchin's secretary, and T.E. Cronk, manager of "The Wilderness Trail," were very happy recipients...

Dr. William J. Frost handed the presidency of Berea College over to Dr. William J. Hutchins in 1920, and when he died he left all his papers to the college.

This year Dr. Elizabeth Peck of the history department, who has been at Berea College "man and boy" since 1912, was made college historian. She immediately undertook to go through those papers.

To her great excitement, being a "Little Colonel" fan, she found two letters from Annie Fellows Johnston, dated 1919 and 1920, in which the author wrote:

"I am very busy with a work I hope to be of profit to Berea, indirectly. It is a book about the mountain people themselves, putting their various problems into a story which I hope will have as wide an influence as my other books seem to have exerted. It is to be called 'A Mountain Mailbag" ... D. Appleton and Company, who will publish the book, are quite enthusiastic."

"How strange," thought Dr. Peck, "that I have never read the book." There was no copy in the college library. And when she wrote the Louisville Free Public Library staff, they reported that not only was the book not in the library, but they could find no record of its publication. Dr. Peck was nonplussed -- but not for long.

She knew Mrs. Johnston had lived with a daughter, Miss Mary Johnston, at Pewee Valley, so she wrote to ask her: "Where is the book?"

The letter, when it arrived at Miss Johnston's home, The Beeches, created great interest. For Miss Johnston had had the original manuscript ever since the beginning of the author's long illness in 1920. It had rested there in Pewee Valley all this time in its original briefcase.

Miss Johnston immediately sent the first two chapters to Dr. Peck, asking her to go over them, explaining that the briefcase contained parts of 16 chapters and a heading for a 17th -- some quite complete, some fragmentary, some only in summary. They were in typescript with notes in Annie Fellows Johnston's handwriting.

Berea wrote back that they wished they might own the manuscript, but could not afford to buy it, and did not know whether in its incomplete state anyone would publish it. But they asked if they might have it on loan for display, especially in the centennial year, so that the thousands of tourists who would come to see Paul Green's festival drama, "The Wilderness Trail," might get still another glimpse of Berea's nostalgic past.

Mary Johnston said she would be delighted to give the manuscript to Berea. She has been wondering for years what she ought to do with it to make it accessible for she knew that interest in Mrs. Johnston's work had never waned. In fact, only last year the 53rd printing of a collection of "Little Colonel" stories was issued.

The theme of the story is unequivocally stated in Chapter 10: the struggles between those people in the mountains, mostly the young, who wanted an education, and those who for various reasons were afraid of it...

... Mrs. Johnston has copied and put together from the author's diary of 1919-1920 some of the relevant notes about her visits to Berea and her trips to the neighboring hills...

... The three who drove from Berea for formal presentation of the manuscript -- Dr. Peck, Miss Charlotte Stephens, who is Dr. Hutchin's secretary, and T.E. Cronk, manager of "The Wilderness Trail," were very happy recipients...

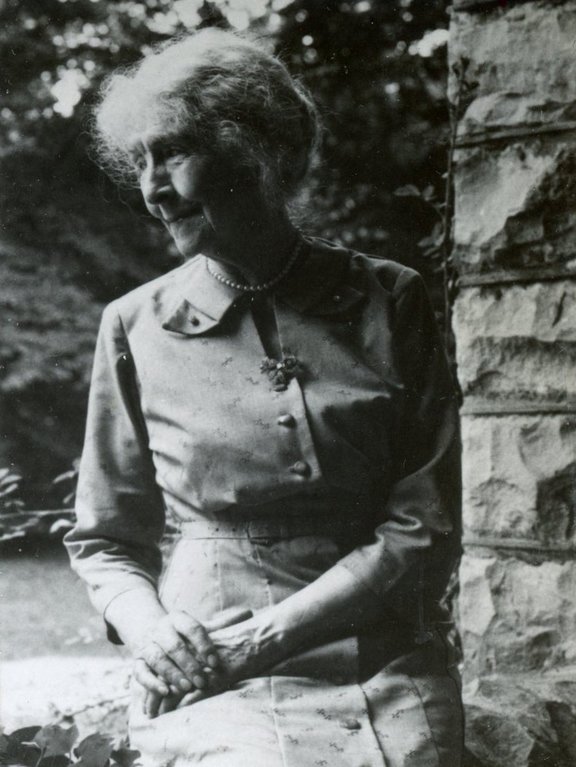

Photo of "Miss Mayme Johnston" taken in the 1940s. Courtesy of the late B. Utley Murphy.

Photo of "Miss Mayme Johnston" taken in the 1940s. Courtesy of the late B. Utley Murphy.

By the 1960s, none of the originals for the characters in her stepmother's books remained in Pewee Valley. They were dead and buried or had moved away. However, three years prior to Mary Johnston's death, the Courier-Journal's Susan Clarke interviewed Mary and her cousin Hallie on The Beech's front porch. The interview, which ran July 19, 1963, noted that Mary employed Walker J. Hardin, Jr., son of the man who inspired the character of the Old Colonel's manservant in the "Little Colonel" Stories, to help her maintain house:

... Miss Mary, who manages "The Beeches" by herself, is able to keep up the authentic loveliness of the house and grounds with the help of Walker, who comes twice a week. "I don't know how I would find things without him," smiles the sprightly Miss Johnston. "I lost a checkbook the other day and looked all over for it. Walker found it beneath a cushion..."

She left Walker $300 in her will.

Death

|

On July 16, 1966, Mary Gardner Johnston died at Pewee Valley Hospital & Sanitarium. Her death was announced in newspapers across America. The Courier-Journal ran her obituary the next day: 'Little Colonel' Illustrator Dies at 93 Miss Mary Gardner Johnston, artist and illustrator of the "Little Colonel" books, died at 6 a.m. yesterday at the Pewee Valley Hospital. She had been there since September with a broken hip. Miss Johnston has lived at The Beeches in Pewee Valley, where her stepmother Annie Fellows Johnston wrote the "Little Colonel" books, which Miss Johnston illustrated. The series was written for young girls. Miss Johnston also exhibited some of her paintings at the J.B. Speed Art Museum. A native of Evansville, Ind., she moved to Pewee Valley when she was 10. She was a member of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church, the Pewee Valley Woman's Club, the Oldham County Historical Society and the Kentucky Historical Society. The funeral will be at 10 a.m. Monday at the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church. Burial will be at 3 p.m. Monday at Oak Hill Cemetery in Evansville. The body is at M.A. Stoess Funeral Home in Crestwood. A lengthy obituary also ran in the Indianapolis Star on July 18: Miss Johnston, 'Little Colonel' Artist Dies LaGrange, Ky. -- Funeral services for Miss Mary Gardner Johnston, 93 years old, Pewee Valley, the illustrator of the "Little Colonel" books, will be held at 10 a.m. today at Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church. Graveside services will be held at 3 p.m. today at Oak Hill Cemetery in Evansville. MISS JOHNSTON, a native of Evansville, died Saturday night at Pewee Valley Hospital. She had lived in Pewee Valley, a small town in Ky. on 146 outside Louisville, which served as the setting for 13 books about Southern life, since 1892. The books, for young girls, were written by her stepmother, Annie Fellows Johnston. They concerned the adventures of a young girl who emulated her Kentucky Colonel grandfather so much she was called the "Little Colonel." A movie was later made about the little girl starring Shirley Temple. PEWEE VALLEY, made famous by the books, now has a museum containing objects common to the era and a "Little Colonel" Bookstore. Miss Johnston painted portraits and landscapes. Some of her work is now on exhibit at the J.B. Speed Art Museum in Louisville and a gallery in LaGrange. She is survived by several cousins. |

|

Postscript

Mary's dying wish was that The Beeches become a shrine to her stepmother. In her will she wrote:

ITEM V.

I give to HELEN O’DELL of 626 South Harlan Avenue, Evansville, Indiana, my mother’s portrait; provided, however, that if within six (6) months of my death my home is made into a shrine, this bequest shall be void. Any transportation charges for shipping the portrait shall be borne by HELEN O’DELL.

ITEM VI.

I give to MARY MUNGER of 2755 Buena Vista, Southwest, Portland, Oregon, if she survives me, the portrait of me (head); provided, however, that if my home is made into a shrine within six (6) months of my death, this bequest shall be void. Any transportation charges for shipping the portrait shall be borne by MARY MUNGER.

ITEM VII.

I devise my home, "THE BEECHES,” in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, to such as shall survive me of JOY BACON WITTWER of Route 4, Box 197, Niles, Michigan, and DR. HILARY E. BACON of 5506 Kemper Road, Baltimore, Maryland; if both survive me they shall take equally in fee simple.

The Pewee Valley Woman's Club, when it was founded in 1952, had hoped to eventually purchase The Beeches as a clubhouse and preserve it as a memorial to Annie Fellows Johnston. However, they wound up purchasing the former Pewee Valley State Bank building on Mt. Mercy the year Mary died. Mary's relatives sold the house to Otis and Virginia Herdt Chaudoin. It remains in private hands today.

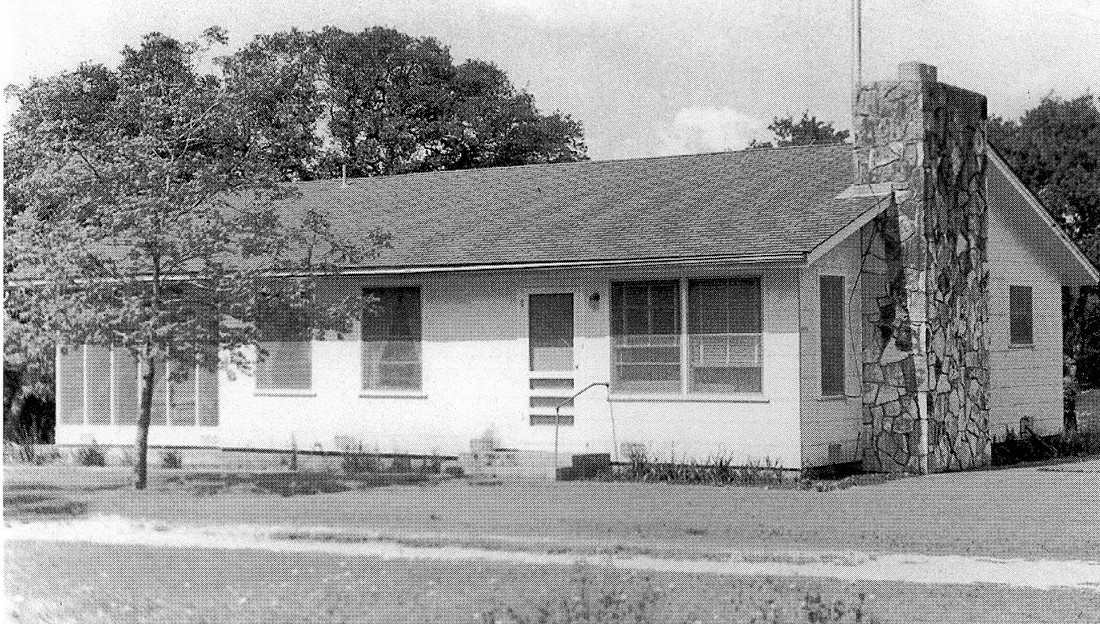

Pen Acres in Boerne suffered a worse fate. The picturesque 1896 structure -- originally built by Charles Schwartz and owned by Annie Fellows Johnston from 1905 until 1911 -- was torn down and replaced by a new home. The 1981 photo below shows the ranch house that replaced it.

Related Links