Mary "Mamie" Craig Lawton (March 31, 1855-January 5, 1934): Wife of General Henry Ware Lawton, Author Annie Fellows Johnston's Amanuesis, and Inspiration for Mrs. Walton's Character in the "Little Colonel" Tales

This brief biography of Mamie Craig Lawton was written by Morgan Voeltz Swanson, direct descendant through Mamie's only son Ranald.

Introduction

Born in Louisville on March 31, 1855, and raised in Pewee Valley, Mary Craig Lawton's friends and family affectionately called her “Mamie.” Her Pewee Valley upbringing left a strong stamp that she carried throughout her life as she followed her soldier husband across the Southwest United States and overseas, and as she returned to Pewee to take on the mantle of family matriarch.

Family Background Reflects, Shapes Regional History

|

|

Mamie’s family history was deeply intertwined with Pewee Valley and the surrounding Louisville region’s growth and development. Her maternal roots included a famed grandfather whose work at well-known local private schools contributed to the region’s reputation as an elite and civilized enclave, while her merchant father’s hat making business exemplified Louisville’s robust commercial development in the mid-1800’s.

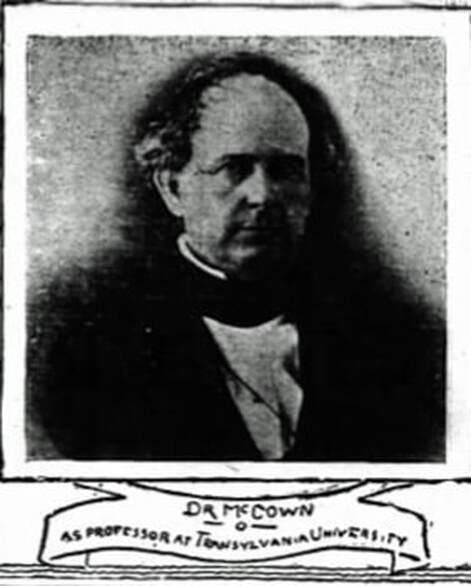

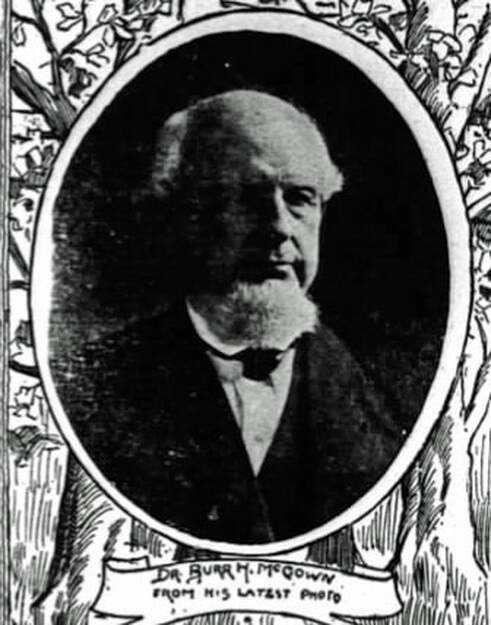

Mamie’s maternal grandfather, Reverend Burr Hamilton McCown, left an enduring stamp on Mamie’s moral and intellectual character. Born in Bardstown, Kentucky on August 25, 1806 McCown’s pride in his own family roots almost certainly permeated the next generations and perhaps made Mamie feel bound to that legacy. In a letter to one of his daughters McCown once referred to his first ancestors to arrive in what is now the United States as six brothers who migrated from county Tyrone, Ireland, in 1728. According to McCown, the brothers were descendants of a Presbyterian family that had previously moved to Ireland to escape religious persecution. McCown’s father, Alexander, was a soldier in the war of independence and later a Kentucky pioneer who joined the Kentucky militia in the War of 1812. McCown’s intellectual and religious development was ahead of its time in terms of open-mindedness and acceptance. The child of Protestant parents, he benefitted in his youth from Bardstown’s status as home to St. Joseph’s, one of the best-reputed schools in the then half-settled state of Kentucky and in the Western region overall, and which he attended. It was a Catholic school where McCown befriended well-known religious leaders of the day and learned multiple languages, but his most important lesson probably came from his experience as a Protestant student among Catholic teachers and classmates. A contemporary to McCown credits this formative experience with the “wide tolerance and advanced liberality which characterized the man in after life,” and which rubbed off on his daughter and, later, his granddaughter Mamie. Reverend McCown’s first wife, Mary McClung Thompson—Mamie’s grandmother—was a prominent citizen in her own right. As the daughter of a Mercer county family family descended from an English officer who had resigned his |

British military commission to support the patriots in the Revolutionary War, Mary’s own historical pedigree matched her husband’s. The couple’s eldest daughter, Anna “Annie” E. McCown—Mamie’s mother—was born on February 11, 1834 in Harrodsburg, Mercer County, Kentucky. Their son, Alexander “Aleck,” was born in 1836, and a second daughter, Letitia, in 1840. The McCowns settled in Anchorage, Kentucky in 1856 and opened a private school, Forest Academy, which soon became known as one of the best educational institutions in Kentucky, and whose presence contributed to the region’s rise in stature as an enclave of high society.

Annie Craig in her youth followed in her teacher father’s footsteps, working as a governess and instructing school. Later in life she often emphasized to her own family the redeeming value of education for helping people rise out of poverty. In 1873 she worked to establish a private, non-denominational educational institution for young ladies in Pewee Valley. When Annie McCown married Alexander Craig, Mamie’s father, in Goshen, Oldhmam County, Kentucky, on February 13, 1854, it was Reverend McCown who performed the ceremony.

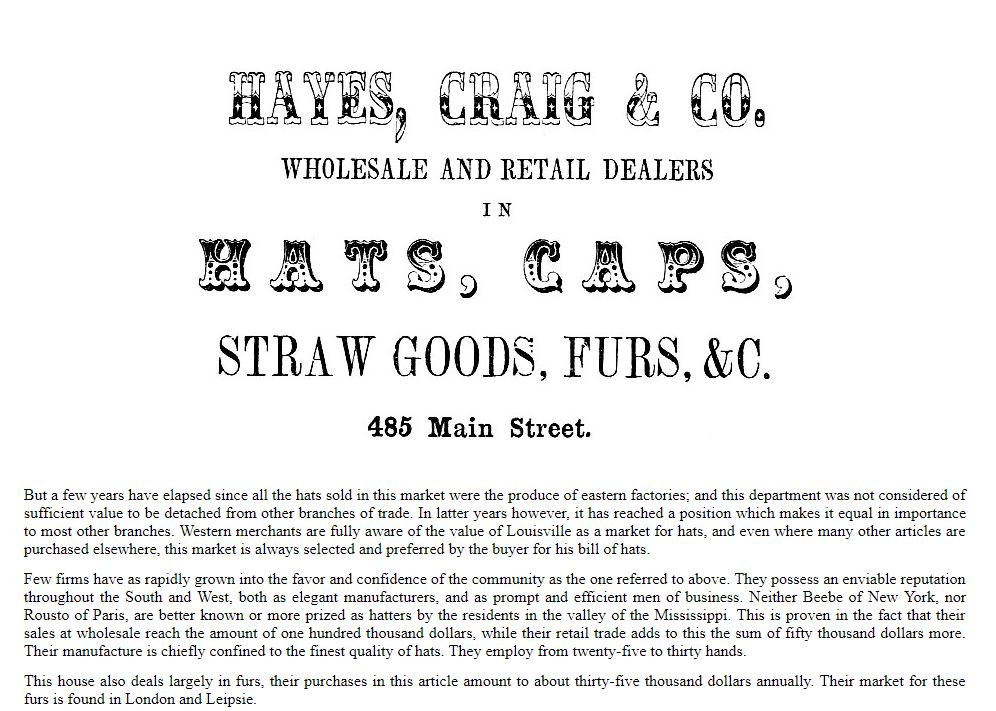

On Mamie’s paternal side, her father, Alexander “Aleck” Craig, did not appear to have famous roots. Census records indicate his children were never even quite sure where he was born—in various records over the years they listed him as born in Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, he became well-known for his successful hat and fur business that thrived during the 1850s and 1860s. The business’s links across the nation and even to Europe reflected Louisville’s emerging status in the 1850s as a booming commercial and industrial center. It benefitted naturally from its proximity to the river, and as of 1855, the new Louisville and Frankfort Railroad linked it overland to the rest of the nation.

On Mamie’s paternal side, her father, Alexander “Aleck” Craig, did not appear to have famous roots. Census records indicate his children were never even quite sure where he was born—in various records over the years they listed him as born in Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, he became well-known for his successful hat and fur business that thrived during the 1850s and 1860s. The business’s links across the nation and even to Europe reflected Louisville’s emerging status in the 1850s as a booming commercial and industrial center. It benefitted naturally from its proximity to the river, and as of 1855, the new Louisville and Frankfort Railroad linked it overland to the rest of the nation.

Advertisements for Mamie's Father's Store in Louisville

Aleck Craig’s store at 485 Main Street occupied a corner building that as of early 1851 had undergone renovations that cemented the company as “…not only one of the leading establishments in their line in Lousiville, but in the whole West.” An ad in 1852 boasted that “but a few years have elapsed since all the hats sold in this market were the product of eastern factories…” and now “Western merchants are fully aware of the value of Louisville as a market for hats…” Another article that same year notes Hayes, Craig and Co.’s reputation throughout the South and West of the US, noting that their wholesale sales reached 100,000 dollars while their retail trade brought an additional 50,000. Their fur business yielded about 35,000 annually, from a market that went as far as London and Leipsie. They employed twenty-five to thirty workers. Within the next five years, the shop expanded to take over two adjoining properties where Craig and his business partners used the buildings’ upper stories for order work and for their wholesale business. Advertisements and favorable newspaper articles in local papers boasted the shop’s stock of hats of all styles and materials, featuring “fur, silk and wool from the finest to the coarsest, of every size, shape, and color…” and in the winter, “ensured a supply of furs, muffs, boas and pelerines.” One such article describes huge piles of hat boxes moving hourly from Hays & Craig’s facility to points of sale within Louisville as well as nationwide. By the eve of the Civil War in 1860, the store had moved to 607 West Main Street. Aleck went on buying trips to Europe, as evidenced by his letters back home to Annie.

Early Childhood

In Annie and Aleck Craig’s household, Mamie grew up in a loving and worldly environment. Shortly after her own birth in 1855, five more siblings soon joined her:

Aleck’s work and its success not only brought in an income that permitted a very comfortable lifestyle for the large family, but also brought with it an awareness of the world, culture, style, and fashion. Education was a household theme as it was in Annie’s childhood home, with Annie and Aleck becoming founding members of a local college for young ladies. Annie Craig was a loving matriarch whose guidance over her household left a strong impression on her eldest daughter. Local author Annie Fellows Johnston wrote of Annie—via a character closely based on her—as “stately and dignified,” noting that her warmth and loving manner balanced her aversion for dirty hands or rumpled collars at the dinner table. According to Johnston, Annie Craig was the kind of grandmother who expected children to behave, tolerated no shenanigans, and inspired good behavior through both modeling and discipline. It was a style that shaped Mamie’s own view of her role. Years later, while raising her own family, Mamie wrote to Annie that she strove to be as good a mother to her own daughter as Annie was to her.

Mamie was five years old when the Civil War began. From her home in Louisville she would have witnessed the city’s transformation into a bustling hub transporting goods and soldiers to furnish the ongoing war efforts. KentuckIy remained neutral during the war and Louisville became an important staging center for Union troops, but the region also harbored numerous Confederate supporters due to the importance of the slave trade to the region’s economy. Mamie’s maternal uncle, Dr. Aleck McCown, joined the Confederate Army in 1861 as a surgeon. She probably observed how her grandfather, Reverend McCown, continued to open the doors of his home and his Forest Academy school to both Union and Confederate supporters, treating them equally—a choice likely born of watching beloved current and former students depart to support both sides. His unbiased stance matched that of the State he lived in and surely influenced his family’s views of the conflict.

- Aleck (November 21, 1856 – January 5, 1934);

- Fannie (February 9, 1859 – March 14, 1933);

- Alice (April 19, 1860 – December 13, 1881);

- Burr Harrison “Harry” (November 15, 1863 – November 1, 1929);

- Louise (October 26, 1865 – September 10, 1938); and

- Merton (1869 – October 24, 1922).

Aleck’s work and its success not only brought in an income that permitted a very comfortable lifestyle for the large family, but also brought with it an awareness of the world, culture, style, and fashion. Education was a household theme as it was in Annie’s childhood home, with Annie and Aleck becoming founding members of a local college for young ladies. Annie Craig was a loving matriarch whose guidance over her household left a strong impression on her eldest daughter. Local author Annie Fellows Johnston wrote of Annie—via a character closely based on her—as “stately and dignified,” noting that her warmth and loving manner balanced her aversion for dirty hands or rumpled collars at the dinner table. According to Johnston, Annie Craig was the kind of grandmother who expected children to behave, tolerated no shenanigans, and inspired good behavior through both modeling and discipline. It was a style that shaped Mamie’s own view of her role. Years later, while raising her own family, Mamie wrote to Annie that she strove to be as good a mother to her own daughter as Annie was to her.

Mamie was five years old when the Civil War began. From her home in Louisville she would have witnessed the city’s transformation into a bustling hub transporting goods and soldiers to furnish the ongoing war efforts. KentuckIy remained neutral during the war and Louisville became an important staging center for Union troops, but the region also harbored numerous Confederate supporters due to the importance of the slave trade to the region’s economy. Mamie’s maternal uncle, Dr. Aleck McCown, joined the Confederate Army in 1861 as a surgeon. She probably observed how her grandfather, Reverend McCown, continued to open the doors of his home and his Forest Academy school to both Union and Confederate supporters, treating them equally—a choice likely born of watching beloved current and former students depart to support both sides. His unbiased stance matched that of the State he lived in and surely influenced his family’s views of the conflict.

After the war ended, and when Mamie was nine years old, her parents purchased a home in Pewee Valley, a secluded locale a dozen miles from Louisville. It could very well have been Reverend McCown, then living just two miles from the property, who noticed it go up for sale by auction and encouraged his daughter and her husband to purchase it. The move brought their growing brood closer to their maternal grandparents, while ensuring that Aleck could easily commute to his shop by way of the railroad that connected Pewee to Louisville. The home, which they called, Edgewood, became the center of Mamie’s family life.

Unfortunately, Aleck Craig did not live to enjoy this new home for long. He died in early 1869 barely four years after having purchased it. The cause of his death is unknown and came suddenly, leaving Annie pregnant with her sixth child. The loss probably thrust Mamie, as the eldest daughter and then in her early teens, into the role of a second mother caring for her young siblings. Fortunately for them, family ties offered a safety net. Reverend McCown, who held a special affection for his oldest daughter and her growing family, and had visited them often at their home in Louisville, probably stepped in to play the role of patriarch after Aleck’s death. He remained an influential presence in the Craig household throughout Mamie’s childhood and youth. Through such close involvement, McCown shaped his beloved granddaughter’s moral fabric, her sense of direction and purpose in life, and her resourceful propensity for initiative.

Also fortunate for the large brood, especially in an era when it would have been deemed “improper” for a widow and mother of the wealthier class to work, they managed to remain financially stable despite the loss of Aleck. The Craig business was dissolved in January 1869 following Aleck’s death, and his portion sold to fellow Pewee Valley resident Orville Truman, whom Aleck had then but recently brought into the business. The money from this sale, supplemented later by inheritance from Reverend McCown and other occasional income, was sufficient to enable Annie and her children to live comfortably.

Unfortunately, Aleck Craig did not live to enjoy this new home for long. He died in early 1869 barely four years after having purchased it. The cause of his death is unknown and came suddenly, leaving Annie pregnant with her sixth child. The loss probably thrust Mamie, as the eldest daughter and then in her early teens, into the role of a second mother caring for her young siblings. Fortunately for them, family ties offered a safety net. Reverend McCown, who held a special affection for his oldest daughter and her growing family, and had visited them often at their home in Louisville, probably stepped in to play the role of patriarch after Aleck’s death. He remained an influential presence in the Craig household throughout Mamie’s childhood and youth. Through such close involvement, McCown shaped his beloved granddaughter’s moral fabric, her sense of direction and purpose in life, and her resourceful propensity for initiative.

Also fortunate for the large brood, especially in an era when it would have been deemed “improper” for a widow and mother of the wealthier class to work, they managed to remain financially stable despite the loss of Aleck. The Craig business was dissolved in January 1869 following Aleck’s death, and his portion sold to fellow Pewee Valley resident Orville Truman, whom Aleck had then but recently brought into the business. The money from this sale, supplemented later by inheritance from Reverend McCown and other occasional income, was sufficient to enable Annie and her children to live comfortably.

Pewee Valley Upbringing Shapes Mamie

Left to right, Mamie's mother Annie Craig, niece Alice Craig Gatchel, and sister Fanny Craig holding her great-niece niece, Alice. From "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," published in 1974 by Pewee Valley's first official historian, Katie Snyder Smith, in honor of Oldham CouLittle Colonel," published in 1974 by Katie Snyder Smith

Left to right, Mamie's mother Annie Craig, niece Alice Craig Gatchel, and sister Fanny Craig holding her great-niece niece, Alice. From "Pewee Valley: Land of the Little Colonel," published in 1974 by Pewee Valley's first official historian, Katie Snyder Smith, in honor of Oldham CouLittle Colonel," published in 1974 by Katie Snyder Smith

Pewee Valley offered Mamie and her siblings a sheltered, rural upbringing a stone’s throw from the busy industrial center. Despite the loss of their father, Mamie and her siblings enjoyed a childhood and youth built around community, friends, education, and compassion. Mamie grew up with a batch of servants in the home, including a gardener and, in at least one instance, four female servants who probably managed cooking, cleaning, and laundry. The house was always open to the community that surrounded them and their life revolved around social occasions. Local press noted that, “the Craig home was always crowded with young persons, who danced in the evenings, played croquet and tennis and practiced at archery.” Mamie and her sisters became belles of Pewee and nearby Louisville. Mamie developed an appreciation for a good social gathering and a flare for planning such festivities, mastering a degree of party-throwing expertise that was unmatched in its capacity to plan a fete with all the trappings of decorations and entertainments.

In the long run, success for the Craig children was a mixed bag. A Pewee Valley neighbor who knew the whole family asserted that “the Craig women were brilliant but the men were ne’er-

In the long run, success for the Craig children was a mixed bag. A Pewee Valley neighbor who knew the whole family asserted that “the Craig women were brilliant but the men were ne’er-

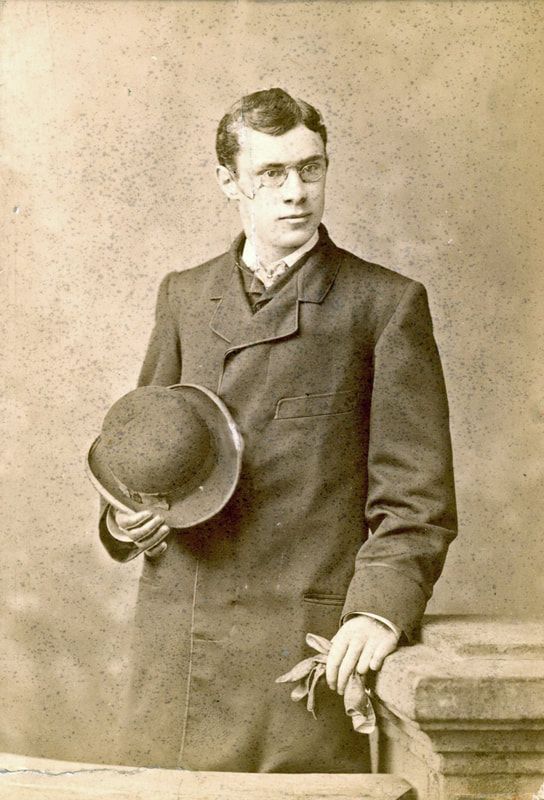

Mamie's brother Merton Craig, courtesy of Susan Lawson.

Mamie's brother Merton Craig, courtesy of Susan Lawson.

do-wells.” While Mamie and her three sisters grew into matriarchs in their own rights, managing households or independent careers, their brothers never held consistent employment of note. Mamie’s youngest brother Merton worked various jobs including as an officer in Battery A of the old First Kentucky Regiment, and later served on the regimental staff of Colonels Biscoe-Hindman and William B. Haldeman. He ended up in Seattle, where he committed suicide in 1922. Mamie’s oldest brother, Alexander, was confined to his home by poor health, and her middle brother Harry was intellectually challenged and depended in youth on his mother, and in adulthood on his older sister, Fannie, to manage his personal affairs and protect him from the influence of local miscreants. In one piece of family lore, Fannie gave Burr money to go out and buy a chicken for dinner. Having accomplished the task, he put the chicken in his pocket and was on his way home when he ran into the two Nock brothers, local miscreants. Somehow they discovered that Burr had money on him leftover from the chicken purchase, and convinced him to use it to to buy alcohol for them. They took him and the liquor to a nearby isolated swampy area to embark on a two-day drinking binge as the dead chicken decayed in Burr’s pocket. Fannie’s righteous rage upon finally finding Harry became the stuff of Pewee Valley legend.

In contrast, the Craig daughters, on balance, grew to become society figureheads in Pewee Valley and beyond. Alice was the outlier, having died shortly after giving birth to her first daughter and namesake. Louise married into a wealthy Louisville family, and Mamie’s own marriage and contributions to her husband’s military career gained national renown. Fannie never married, instead becoming the next-generation backbone of the Edgewood household—someone had to care for Harry and the aging Annie—and a mainstay of the Pewee Valley community. A graduate of the Kentucky College for Young Ladies, Fannie followed in her educator grandfather and mother’s footsteps, teaching at her alma mater and later opening a private school, the Villa Ridge School, in a property behind Edgewood. She taught piano lessons out of her home, and was a very active member of the local Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church where she served as librarian, organist and Sunday school teacher. She became well-known to everyone in the community, and Annie Fellows Johnston described a character based on Fannie as “the life of every party and picnic in the neighbourhood” and “everybody’s confidant.” According to Johnston, Fannie held a special draw for all the local children, whom she invited to Edgewood after church to indulge in story sessions and homemade treats like beaten biscuits, candied orange slices, and brandied peaches the size of a half-dollar. In addition to keeping the household running, Fannie’s work brought income to the family at a time when their inheritance from Reverend McCown and Aleck Craig may have begun to run out.

Mamie, by the time she reached adulthood, had established herself as intelligent, spirited, and warm. She seemed unwilling to show a negative attitude to others, and directed her attention to joyful things. An engaging and effusive comrade, she was affectionate with friends in both spoken word and through her letters, skilled at using language to convey love, affection, support, and praise. She expressed admiration for qualities she saw in those around her including “big-heartedness, broad-mindedness, Christ-like love for his fellow creatures, and charity that thinketh no evil.” They were characteristics that she herself seemed to share. Mamie had established the qualities that would win her a strong following of friends throughout her life, and that would soon play a role in attracting the attentions of the tall, handsome soldier who would become her husband.

In contrast, the Craig daughters, on balance, grew to become society figureheads in Pewee Valley and beyond. Alice was the outlier, having died shortly after giving birth to her first daughter and namesake. Louise married into a wealthy Louisville family, and Mamie’s own marriage and contributions to her husband’s military career gained national renown. Fannie never married, instead becoming the next-generation backbone of the Edgewood household—someone had to care for Harry and the aging Annie—and a mainstay of the Pewee Valley community. A graduate of the Kentucky College for Young Ladies, Fannie followed in her educator grandfather and mother’s footsteps, teaching at her alma mater and later opening a private school, the Villa Ridge School, in a property behind Edgewood. She taught piano lessons out of her home, and was a very active member of the local Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church where she served as librarian, organist and Sunday school teacher. She became well-known to everyone in the community, and Annie Fellows Johnston described a character based on Fannie as “the life of every party and picnic in the neighbourhood” and “everybody’s confidant.” According to Johnston, Fannie held a special draw for all the local children, whom she invited to Edgewood after church to indulge in story sessions and homemade treats like beaten biscuits, candied orange slices, and brandied peaches the size of a half-dollar. In addition to keeping the household running, Fannie’s work brought income to the family at a time when their inheritance from Reverend McCown and Aleck Craig may have begun to run out.

Mamie, by the time she reached adulthood, had established herself as intelligent, spirited, and warm. She seemed unwilling to show a negative attitude to others, and directed her attention to joyful things. An engaging and effusive comrade, she was affectionate with friends in both spoken word and through her letters, skilled at using language to convey love, affection, support, and praise. She expressed admiration for qualities she saw in those around her including “big-heartedness, broad-mindedness, Christ-like love for his fellow creatures, and charity that thinketh no evil.” They were characteristics that she herself seemed to share. Mamie had established the qualities that would win her a strong following of friends throughout her life, and that would soon play a role in attracting the attentions of the tall, handsome soldier who would become her husband.

Mamie’s Courtship and Marriage to Henry W. Lawton

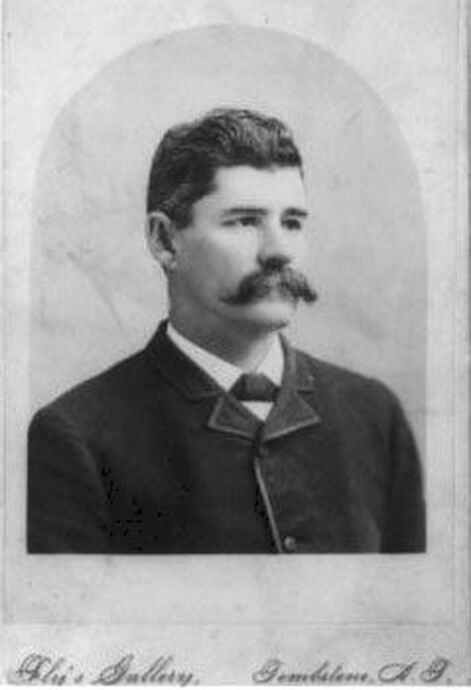

|

Mary’s life was forever changed when she met and married Henry Ware Lawton, an up-and-coming Captain in the United States Army. His career took her far from Pewee Valley, though Mamie’s home and family were never far from her thoughts, and the values and experiences she picked up in Pewee never left her.

Henry recorded their first meeting in a letter he penned to a friend in 1887. According to his account, the two met by chance while both were passing through the city of St. Louis, then a major urban center connecting the growing nation’s East and West. “I had been acting Inspector General of the Department of Arkansas, Head Quarters in Little Rock,” Henry explained to the friend, “and was on my way from there to take part in the trouble in Colorado, in the spring of ’81… I stopped over a few days…” The cause for Mary’s visit to St. Louis is unknown, but it is possible that she was being deliberately circulated through broader social circles in the hopes of encountering possible suitors. Her pool of options in the tiny community of Pewee Valley would have been limited to begin with, but was especially so given the staggering losses that Kentucky’s male population had experienced in the Civil War. An obvious solution, especially in the eyes of a socially-inclined and caring mother like Annie Craig, would have been to expand her daughter’s prospects by making visits to friends in other cities, and the family almost certainly would have had connections in St. Louis established from Aleck’s hat-making years if from no other source. If indeed it was a deliberate plan, it worked. When the couple first crossed paths it was a fortunate chance encounter. As Henry noted, “one day when I got into the Hotel elevator, a young lady got in the other side from the ladies entrance. I liked her looks, met and was introduced that evening.” Mamie might very well have liked Henry’s looks in return. He was a towering six foot four inches tall and handsome, sporting thick dark hair and gentle dark eyes over an enormous floppy mustache. His soldier image may also have played an initial role in attracting Mamie, who later alluded in a letter to a friend to a longstanding admiration for “uniformed men.” Despite such sentiments, Mamie must have known that choosing to pursue a relationship with a soldier would potentially pull her away from her cultivated Pewee Valley home to rough-and-tumble, often lonely military posts on civilization’s fringes. Her grandfather’s tales of ancestors |

serving in the Revolutionary War, or Mamie’s own familiarity with the sight of Civil War soldiers—including her own uncle—during her childhood, may have opened her mind to a soldier suitor. And once they got to know each other, their complementary personalities probably overshadowed any doubts.

At first glance, it might have seemed that Henry Lawton’s lower middle class background would clash with Mamie’s refined Pewee Valley upbringing. The son of a millwright raised on his uncle’s Indiana farm, Henry was accustomed to a modest lifestyle, hard work, and rough country living. He enlisted to fight in the Civil War at the tender age of sixteen and later turned down a stint at Harvard Law School to return to the army life that had gotten into his blood. By the time he met Mamie, years spent in army encampments had honed his innate high tolerance for hard work and discomfort. He possessed modest tastes, some introverted tendencies, and a disdain for fuss and ceremony. Mamie was the opposite on most of those areas. But perhaps more important: they shared an ability to connect with people and to form close and lasting friendships. Henry’s loyalty to his community of soldiers mirrored Mamie’s affection for her own Pewee Valley community. He kept in close touch with childhood friends despite the fact that he seldom returned to his hometown, and was very open in sharing his thoughts and emotions with them throughout his life. In commanding his soldiers, Henry was always on the lookout for their welfare, and a military colleague recalled years later how Henry, even when serving in leadership positions, “was one of the boys himself, and could work with them and sympathize with them,” and that Henry “never considered himself better than anybody else.”

Henry departed St. Louis the day after meeting Mamie, according to the letter he later wrote to his friend, but they kept in touch. They became engaged in September, 1881, just six months after their first meeting, while Mamie was visiting family friends John and Ida Wilcox at Fort Clark, Texas, where Henry was then serving. The delighted chaperone, who had known Henry for years, reported back to Mamie’s mother with effusive praise for her future new son-in-law. “Your son in law in prospective,” he wrote, “is one of the finest fellows in the world. Educated at Cambridge, talented, generous to a fault—a man every inch of him…your daughter will get a number one husband and you a son in law of whom you may be firstly proud.”

The couple launched plans for a wedding in 1882 that probably would have been quite a production; Mamie’s sisters married to much fanfare and extensive local press coverage. But the plan changed in the fall of 1881 when Mamie wrote to Lawton to come to Pewee Valley as soon as possible because her younger sister, Alice, had been taken seriously ill. Fearing death, Alice wanted to be present when Mamie and Lawton were married and had asked that the wedding date be moved up. Lawton requested a leave of absence for November 1-December 31 to go to Pewee Valley.

Mamie and Henry Lawton were married at Edgewood on the twelfth of December, 1881. The ceremony was a quick, quiet, and bittersweet event at Alice’s bedside in one of the high-ceilinged upstairs bedrooms. Minister S.E. Bass—Lawton’s former commander from his Civil War regiment, the 30th Indiana—conducted the ceremony. Annie Craig served as witnesses, and Alice’s doctor and husband were also present. Alice died the next day. Shortly after, Mamie packed her things and, likely following a tearful farewell at Pewee Valley’s train depot, boarded a train to Louisville with her husband en route to a new life as an army wife in the West.

At first glance, it might have seemed that Henry Lawton’s lower middle class background would clash with Mamie’s refined Pewee Valley upbringing. The son of a millwright raised on his uncle’s Indiana farm, Henry was accustomed to a modest lifestyle, hard work, and rough country living. He enlisted to fight in the Civil War at the tender age of sixteen and later turned down a stint at Harvard Law School to return to the army life that had gotten into his blood. By the time he met Mamie, years spent in army encampments had honed his innate high tolerance for hard work and discomfort. He possessed modest tastes, some introverted tendencies, and a disdain for fuss and ceremony. Mamie was the opposite on most of those areas. But perhaps more important: they shared an ability to connect with people and to form close and lasting friendships. Henry’s loyalty to his community of soldiers mirrored Mamie’s affection for her own Pewee Valley community. He kept in close touch with childhood friends despite the fact that he seldom returned to his hometown, and was very open in sharing his thoughts and emotions with them throughout his life. In commanding his soldiers, Henry was always on the lookout for their welfare, and a military colleague recalled years later how Henry, even when serving in leadership positions, “was one of the boys himself, and could work with them and sympathize with them,” and that Henry “never considered himself better than anybody else.”

Henry departed St. Louis the day after meeting Mamie, according to the letter he later wrote to his friend, but they kept in touch. They became engaged in September, 1881, just six months after their first meeting, while Mamie was visiting family friends John and Ida Wilcox at Fort Clark, Texas, where Henry was then serving. The delighted chaperone, who had known Henry for years, reported back to Mamie’s mother with effusive praise for her future new son-in-law. “Your son in law in prospective,” he wrote, “is one of the finest fellows in the world. Educated at Cambridge, talented, generous to a fault—a man every inch of him…your daughter will get a number one husband and you a son in law of whom you may be firstly proud.”

The couple launched plans for a wedding in 1882 that probably would have been quite a production; Mamie’s sisters married to much fanfare and extensive local press coverage. But the plan changed in the fall of 1881 when Mamie wrote to Lawton to come to Pewee Valley as soon as possible because her younger sister, Alice, had been taken seriously ill. Fearing death, Alice wanted to be present when Mamie and Lawton were married and had asked that the wedding date be moved up. Lawton requested a leave of absence for November 1-December 31 to go to Pewee Valley.

Mamie and Henry Lawton were married at Edgewood on the twelfth of December, 1881. The ceremony was a quick, quiet, and bittersweet event at Alice’s bedside in one of the high-ceilinged upstairs bedrooms. Minister S.E. Bass—Lawton’s former commander from his Civil War regiment, the 30th Indiana—conducted the ceremony. Annie Craig served as witnesses, and Alice’s doctor and husband were also present. Alice died the next day. Shortly after, Mamie packed her things and, likely following a tearful farewell at Pewee Valley’s train depot, boarded a train to Louisville with her husband en route to a new life as an army wife in the West.

Mamie as a Military Wife in the West

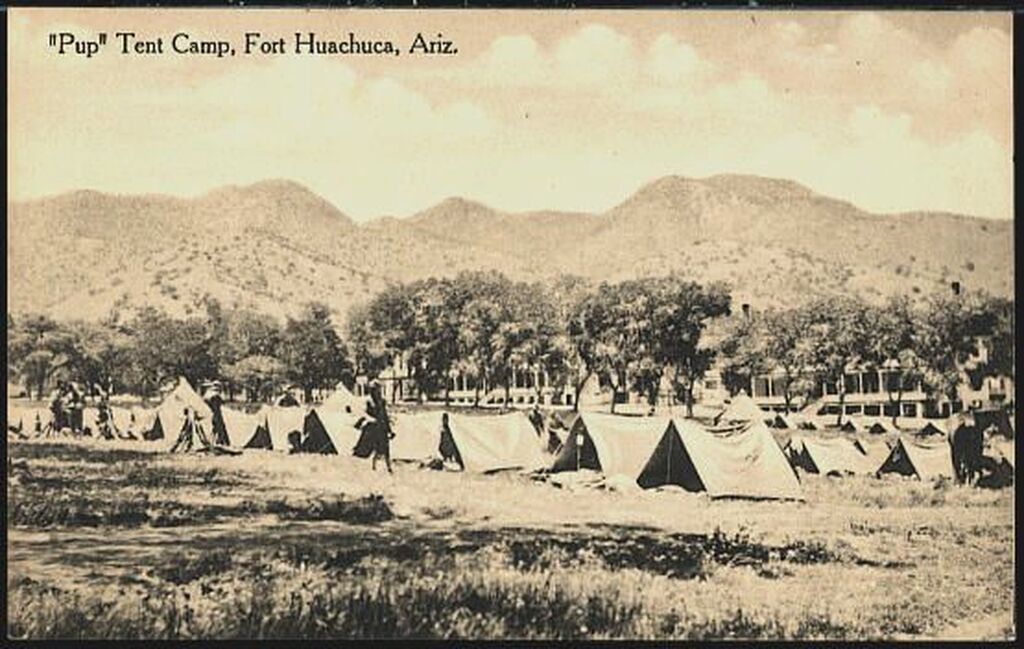

Immediately following their wedding, Mamie accompanied Henry to a succession of military posts across the southwest. Her optimistic nature and love of community enabled her to thrive in this new world that represented a harsh change from her comfortable Pewee Valley home. They proceeded first to the headquarters of the Military District of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico Territory, where Lawton served as Acting Engineer from January, 1882 to October, 1883. They later transferred to Fort Stanton, New Mexico Territory, where Lawton commanded troops until May, 1884. Finally, duty took them to Fort Huachuca, Arizona Territory, which became their home until July 1887. Mamie’s brother, Merton Craig, years later told a reporter that “my sister’s devotion to her husband was admirable. She always wanted to be with him, and she felt that she could brave any danger that he could . . . When he would get orders to go anyplace Mrs. Lawton would immediately begin to pack up and get ready to accompany him.” Such devotion came with sacrifice. Life on a military post was rough for even the toughest soldiers, who commonly complained of extreme temperatures, filthy conditions, bad food, and pervasive disease. Henry’s work often took him away from the fort for days, weeks, or even months at a time, leaving Mamie to care for the household alone.

Departing Pewee, Mamie exchanged groomed lanes that veined gentle hills for dirt roads that scored dusty grassland. She swapped dignified trees that blotted shade across civilized lawns for starving oaks that twisted toward white-hot sky. Fortunately, Mamie’s optimistic bent and eye for the beauty around her found plenty to enjoy in the dramatic western expanse. If Annie Fellows Johnson’s descriptions of fort life in her Little Colonel books are, indeed, based on comments Mamie shared with her, they recount a world in which rugged nature offered freedom and joy. Henry understood his wife’s pleasure in noticing the beauty of her surroundings and helped feed her interest. While away from Fort Huachuca on campaign, he once wrote to her about the interesting birds, bugs and plants he encountered, including “a great variety of doves” and another bird “that makes a noise just like a kitten mewing, not like a cat but a little kitten, and if you did not know it was not you would be certain a kitten was about.” He even planned to send her specimens of an interesting red bug, expecting that “you could color your lemonade and make strawberry ice cream without strawberries.”

Departing Pewee, Mamie exchanged groomed lanes that veined gentle hills for dirt roads that scored dusty grassland. She swapped dignified trees that blotted shade across civilized lawns for starving oaks that twisted toward white-hot sky. Fortunately, Mamie’s optimistic bent and eye for the beauty around her found plenty to enjoy in the dramatic western expanse. If Annie Fellows Johnson’s descriptions of fort life in her Little Colonel books are, indeed, based on comments Mamie shared with her, they recount a world in which rugged nature offered freedom and joy. Henry understood his wife’s pleasure in noticing the beauty of her surroundings and helped feed her interest. While away from Fort Huachuca on campaign, he once wrote to her about the interesting birds, bugs and plants he encountered, including “a great variety of doves” and another bird “that makes a noise just like a kitten mewing, not like a cat but a little kitten, and if you did not know it was not you would be certain a kitten was about.” He even planned to send her specimens of an interesting red bug, expecting that “you could color your lemonade and make strawberry ice cream without strawberries.”

Mamie lost her year-old daughter, Annie, while Henry was stationed in the West. She is buried at Ft. Huachuca in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Morgan Voeltz Swanson.

Mamie lost her year-old daughter, Annie, while Henry was stationed in the West. She is buried at Ft. Huachuca in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Morgan Voeltz Swanson.

Instead of the physical comforts of her Pewee Valley home, Mamie faced heat, cold, dust, and often squalid camp conditions. Fortunately, some luxuries afforded by Lawton’s rank would have softened the adjustment to a large degree. The couple lived in officers’ quarters, which were much more comfortable than the barracks that housed the unmarried soldiers. Mamie also likely had household help—Henry hired a “chinaman” to assist while they were living in Huachuca. Nonetheless, the family was not immune to the worst impacts of a hard lifestyle. Probably due to dirty conditions and lack of proper medical care, they lost three babies during their time in the West—two in infancy, and one at just over a year old. Following the loss of this third child, whom they had named Annie, Mamie poured out her anguish in a letter to her mother. “I cannot imagine God would want us to suffer this way for long,” she wept on paper.

Living on military forts, Mamie also grappled with isolation as never before. Instead of a commuter rail offering multiple daily links to a bustling metropolitan center, she could access the outside world only by intermittent stagecoach or military mail deliveries. Instead of the elite company of well-mannered gentlemen and girlfriends’ frequent visits she enjoyed in Pewee, Mamie found herself among dirty, crass, and uneducated soldiers and a small pool of potential female companions. This very isolation, however, spawned close-knit communities that probably went the furthest in making Mamie feel at home. The communities she encountered were probably not unlike what she knew in Pewee Valley, and likely thrilled to welcome a new member with Mamie’s easy skill at conversation and flare for planning get-togethers and excursions. Just as her own family had always opened their Pewee Valley home to neighbors, Mamie opened the Lawton home to Henry’s military colleagues and their families. Such friends later recalled for reporters that, “Mrs. Lawton…was known to nearly every officer in the service. To them all she represented the truest type of a soldier’s wife, and every officer in the service from the youngest Lieutenant to the commanding General was ready to do anything in his power for Mrs. Lawton.” In addition to charming her peers, Mary’s winning personality and flair as a hostess helped her impress Henry’s superiors, making her a boon to her husband’s career. On at least one occasion, Henry, while away on a campaign, wrote to ask Mamie to entertain his superiors when they visited, confident that they would depart charmed.

The Lawtons returned to “civilization” in July 1887 after Henry’s work in the 1886 Geronimo campaign earned him a coveted posting within the Inspector General’s Department at Fort Meyer, Virginia. They departed the Southwest having experienced its worst hardships and won its greatest rewards in the form of a lasting set of friends and colleagues. In later years, Mamie would rejoice at reunions with the families she and Henry met during their time in the West, proof that she used her time with them to build close and permanent friendships.

Living on military forts, Mamie also grappled with isolation as never before. Instead of a commuter rail offering multiple daily links to a bustling metropolitan center, she could access the outside world only by intermittent stagecoach or military mail deliveries. Instead of the elite company of well-mannered gentlemen and girlfriends’ frequent visits she enjoyed in Pewee, Mamie found herself among dirty, crass, and uneducated soldiers and a small pool of potential female companions. This very isolation, however, spawned close-knit communities that probably went the furthest in making Mamie feel at home. The communities she encountered were probably not unlike what she knew in Pewee Valley, and likely thrilled to welcome a new member with Mamie’s easy skill at conversation and flare for planning get-togethers and excursions. Just as her own family had always opened their Pewee Valley home to neighbors, Mamie opened the Lawton home to Henry’s military colleagues and their families. Such friends later recalled for reporters that, “Mrs. Lawton…was known to nearly every officer in the service. To them all she represented the truest type of a soldier’s wife, and every officer in the service from the youngest Lieutenant to the commanding General was ready to do anything in his power for Mrs. Lawton.” In addition to charming her peers, Mary’s winning personality and flair as a hostess helped her impress Henry’s superiors, making her a boon to her husband’s career. On at least one occasion, Henry, while away on a campaign, wrote to ask Mamie to entertain his superiors when they visited, confident that they would depart charmed.

The Lawtons returned to “civilization” in July 1887 after Henry’s work in the 1886 Geronimo campaign earned him a coveted posting within the Inspector General’s Department at Fort Meyer, Virginia. They departed the Southwest having experienced its worst hardships and won its greatest rewards in the form of a lasting set of friends and colleagues. In later years, Mamie would rejoice at reunions with the families she and Henry met during their time in the West, proof that she used her time with them to build close and permanent friendships.

Life in Civilization: Washington and Redlands…

The Lawtons’ hard work and sacrifice in frontier posts finally earned them a few years of comfortable living. In September, 1888 Henry was appointed Assistant in the Inspector General’s Office, a promotion that brought a move to Washington, D.C. The family thrived in the metropolitan capitol. A healthy son, Manley, was born on July 29, 1887. Three daughters quickly followed as the couple welcomed Frances on January 28, 1889; Catherine on May 20, 1890; and Louise on June 21, 1892. Henry’s work for the Inspector General’s department required frequent travel to inspect military instillations across the country, and Mamie and the children likely accompanied him on the trips, which took them to nearly every corner of the country. According to the Inspector General’s office, “one tour of special inspections embraced visits to most of the posts in the West…and down the Pacific coast to Los Angeles, Cal., and thence to Washington again. Another embraced inspections on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and Mississippi River from Wilmington, N.C., via St Augustine, Fla., to Montgomery, New Orleans, Vicksburg, Memphis, Little Rock, and intermediate points, to Duluth, Minn., specially considering engineer inspections.” These travels might have helped open Mamie and Henry’s eyes to the possibility of relocating to California. Indeed, the couple had long dreamed of a permanent residence, and Lawton, in a letter to Mamie in 1886, had mentioned his wish to have enough money to purchase a house for their children to have a “real home.” Lawton had also expressed to friends his hope of someday living near his older brother and son’s namesake, Manley, who lived in San Francisco.

They got that chance to make such a move in December 1893, when Lawton was assigned Inspector General for the Department of Arizona, headquartered in Los Angeles. In the spring of 1894, Mamie and Henry purchased a home in the southern California community of Redlands. Nestled in the low coastal mountains east of Los Angeles, Redlands had sprung up a few decades prior as a small cluster of orange and fruit farms that thrived in the region’s Mediterranean climate. By the early 1890s, the fruit trade’s profits, along with that same attractive climate, drew the attention of members of Los Angeles’ wealthy class who transformed Redlands into an elite enclave sprinkled with trendy new Victorian mansions. The area probably reminded Mamie of a Southern California version of her own beloved hometown. The Lawtons’ new twelve-acre ranch perched on a knoll at the corner of Cypress and Sunnyside Avenues, offering views of surrounding orange groves, mountains, and the San Bernardino Valley below. Local journalists who took note of the high profile purchase described the site as “beautifully rolling, sloping to the west, thus giving a commanding view … on all sides.”

Henry’s military salary was not extravagant, so the means to purchase the home almost certainly came from Mamie’s side. Purchased in her name for an original price tag of $15,000, it was a “modest” dwelling at the time. They quickly moved to renovate it to suit Mamie’s refined tastes, an effort that required some financial acrobatics including a $2000 loan. The end result, according to local press, was “a beautiful residence of a dozen rooms…full of curios and souvenirs gathered from all parts of the Union…” Lawton spent much of his time working from home even though he was headquartered in Los Angeles, and the couple expressed to friends that they intended to spend the rest of their lives there.

Nonetheless, Henry’s work continued to pull him around the country, suggesting that the family may not have spent much uninterrupted time in their new abode. In September, 1894, Henry was assigned Inspector General of the Department of the Colorado, headquartered in Denver, and in April, 1895, he became inspector general of the southern section district, headquartered at Santa Fe, New Mexico. The headquarters for this last position was soon transferred to Los Angeles, however, likely enabling a return to Redlands. Nonetheless, a life of calm in the California hills was to remain an elusive dream.

Henry’s military salary was not extravagant, so the means to purchase the home almost certainly came from Mamie’s side. Purchased in her name for an original price tag of $15,000, it was a “modest” dwelling at the time. They quickly moved to renovate it to suit Mamie’s refined tastes, an effort that required some financial acrobatics including a $2000 loan. The end result, according to local press, was “a beautiful residence of a dozen rooms…full of curios and souvenirs gathered from all parts of the Union…” Lawton spent much of his time working from home even though he was headquartered in Los Angeles, and the couple expressed to friends that they intended to spend the rest of their lives there.

Nonetheless, Henry’s work continued to pull him around the country, suggesting that the family may not have spent much uninterrupted time in their new abode. In September, 1894, Henry was assigned Inspector General of the Department of the Colorado, headquartered in Denver, and in April, 1895, he became inspector general of the southern section district, headquartered at Santa Fe, New Mexico. The headquarters for this last position was soon transferred to Los Angeles, however, likely enabling a return to Redlands. Nonetheless, a life of calm in the California hills was to remain an elusive dream.

Back into Battle: Cuba and the Philippines

Despite the lure of a tranquil life in the warm California hills, Henry’s penchant for action yanked the family away from their domestic respite. In the late 1890s as the United States began inching toward war with Spain in Cuba and the Philippines, where local forces were revolting against Spanish colonial rule, Henry asked to be given service in the Field. Once again Mamie embraced the new worlds by focusing on her newfound community.

Henry’s request for Field service was granted in May, 1898, when he was appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers and assigned to lead an infantry division during the United States Army’s first strategic march into Cuba. Mamie and the children did not accompany him, and probably eagerly awaited letters from Henry or news of the engagement. During coming months, Henry and his troops were involved in some of the main battles to dislodge Spanish forces, and when the main fighting was over he served a stint as Military Governor, responsible for maintaining security and running all functions of civil government in U.S.-controlled areas. It was work that kept the couple apart for the longest time since Henry’s service in the Geronimo campaign more than a decade before. When he returned to the United States in October, 1898, Mamie was eagerly waiting for him outside the Port of New York. The reunited family soon after made a visit to Pewee Valley, where reporters noted the children’s adoration for Henry, and how he broke away from an interview to spend time with them. When he received notification of his pending assignment to the Philippines within three months of his return from Cuba, it was probably clear in Mamie’s mind that she would not put up with yet another separation, especially one that would put half the globe between them. When Henry departed for Manila in January 1899, she and the four children accompanied him. They sailed from New York City in the transport “Grant,” making the fifty-five day voyage by way of the Suez Canal and arriving in Manila in March, 1899.

Henry’s request for Field service was granted in May, 1898, when he was appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers and assigned to lead an infantry division during the United States Army’s first strategic march into Cuba. Mamie and the children did not accompany him, and probably eagerly awaited letters from Henry or news of the engagement. During coming months, Henry and his troops were involved in some of the main battles to dislodge Spanish forces, and when the main fighting was over he served a stint as Military Governor, responsible for maintaining security and running all functions of civil government in U.S.-controlled areas. It was work that kept the couple apart for the longest time since Henry’s service in the Geronimo campaign more than a decade before. When he returned to the United States in October, 1898, Mamie was eagerly waiting for him outside the Port of New York. The reunited family soon after made a visit to Pewee Valley, where reporters noted the children’s adoration for Henry, and how he broke away from an interview to spend time with them. When he received notification of his pending assignment to the Philippines within three months of his return from Cuba, it was probably clear in Mamie’s mind that she would not put up with yet another separation, especially one that would put half the globe between them. When Henry departed for Manila in January 1899, she and the four children accompanied him. They sailed from New York City in the transport “Grant,” making the fifty-five day voyage by way of the Suez Canal and arriving in Manila in March, 1899.

To Mamie, the bustling tropical capitol was a fascinating adventure that offered her active mind plenty of fodder to thrive. Summing up to one friend how she spent her days, she noted, “I try to keep busy, and usually succeed. Everybody is very nice to me…and so I get along very well.” Probably due to her husband’s rank, the family was housed in a large colonial-style mansion that Mamie good-humoredly referred to as “my palace” and whose physical comforts and wait staff she undoubtedly enjoyed. Mamie also took interest in Philippines history, reading about it during the long voyage to Manila, and later her letters to friends showcased fascination with all aspects of her new surroundings from the people, the markets, and even the flora and fauna that she discovered. She and the children went around the city with guards and an interpreter, all of whom Mamie befriended. She noted to a friend that they went driving every afternoon, relying on the breeze swept up by the carriage’s movement as a source of relief from the tropical climate. “We … keep as cool as we can during the midday heat,” she explained to the friend. “Our evenings are really delightful, but it is intensely hot from 10 to 4 in the day…” In addition to daily outings, her letters home referred to engagements with other military families, such as dinners during which she was fascinated by officers’ talk about their trips to the interior of the islands. She also met local families, and in one letter described her children playing with Filipino companions and showing them their paper dolls. Following one of their expeditions about town she wrote to a friend “I want while here to collect you some leaves of curious plants and tress, and will write under them what they are, and how used. One use of the large ones is to wrap things in, instead of paper, in the markets. Another is to polish the floors or fine tables. A smaller, sort of pepper leave, the natives wrap a bean in, that they are very fond of, and that grows like a date, and chew the whole, making their lips and teeth very red. The women smoke and chew just like men.”

Despite finding pleasure in her new environment, Mamie remained mindful of the violent conflict that had brought them to the Philippines in the first place. Once she wrote to a friend that she could hear weapons firing where fighting was taking place outside the city, just three miles from the home. “We could hear firing very distinctly for some time,” she noted, “and there has been a little more this morning. As all the ambulances … with sick and wounded, pass right by us we feel that the firing means something indeed.”

Mamie closely followed her husband’s work as his troops strove to drive out the Spanish forces, conducting some of the conflict’s most significant early military engagements. Mamie requested an Army map to track his movements around the interior of Luzon, the Philippine archipelago’s largest island, as Henry led campaigns to capture Santa Cruz, conducted an attack on San Rafael, and captured San Isidro. Once, Mamie and the children drove out to an army encampment on Manila’s outskirts to watch her husband and his troops preparing for such an expedition. She recounted the experience to a friend with her characteristic optimism. The camp, she wrote, was “beautifully situated in a mango grove with coconuts, palms and bananas all around.” She observed that the soldiers were “an interesting as well as a pretty sight, so many men going into camp, settling as systematically as clockwork. They were, to a man, cheerful, brave and ready.”

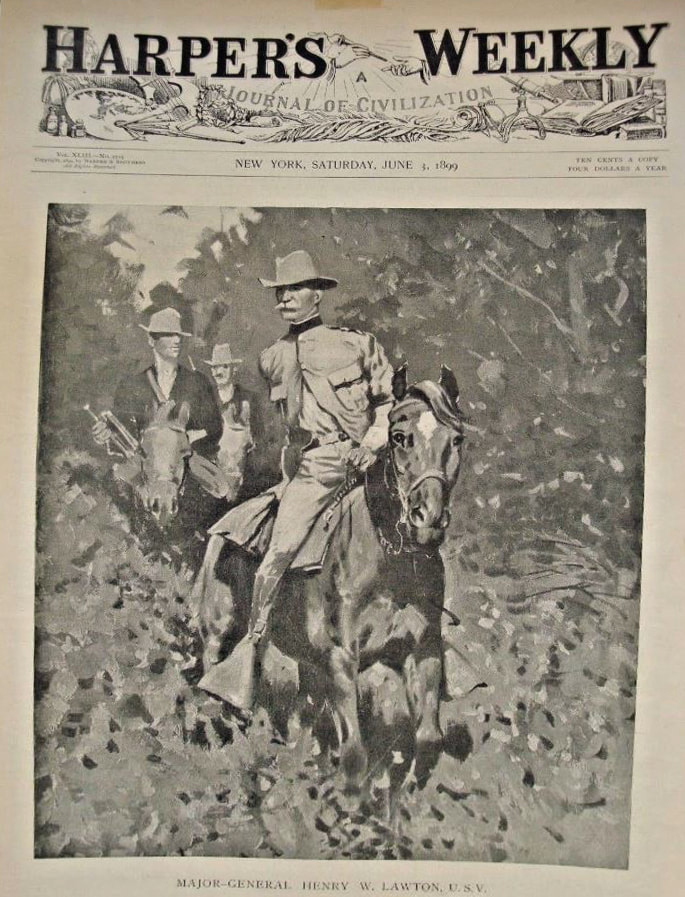

When Henry’s work earned him promotion to General in June, 1899, Mamie was ecstatic and wrote to friends celebrating his new title, “General Lawton—isn’t it glorious?” That same month, he was placed in command of the U.S. forces defending Manila. On at least one occasion Mamie accompanied him and other officers to observe a nearby battle, with their then-eleven year old son, Manley in tow. Together they sat “coolly in an unprotected boat close to the shore during the fighting, with the bullets splashing about,” she recounted to a friend. This firsthand awareness of the conflict allowed her to develop nuanced opinions on the situation’s complications and the outlook for peace. “I find a solution of the Philippines a very difficult question,” she wrote to a friend, using metaphor to touch on the question of the United States’ involvement. “We can not eat them [the Philippines], nor throw them in the alley when no one is looking.”

When she wasn’t directly supporting her husband, Mamie, as always, was finding ways to strengthen the community fabric that surrounded her. This time, her primary focus became the American soldiers who served with her husband and to whose work she felt intimately connected—for reasons beyond family ties. The military hospital was located a block from her “palace,” and as she observed in a letter to a friend, “the cascoes [sic] bearing the wounded, sick and dead go directly by my door …” During her visits to the hospital, she continued, “it makes my heart ache, but gives me a lesson in patience, cheerfulness, endurance and unselfishness.” It was a perspective that showed the stamp of her grandfather’s legacy, as did her decision to undertake missionary work to improve the recovering soldiers’ situations in the only way that was within her control—by visiting them to offer comforting messages and moral support. Mamie and another officer’s wife organized the “Manila Aid Society” to undertake this mission. The Aid Society began with less than twenty members who met in Mamie’s home, and quickly expanded until they had enough manpower to sustain daily visits to each of the approximately 2,500 sick and wounded soldiers in and around Manila. Members organized themselves into “visiting committees,” selected reading materials for the soldiers that would be “cheering and light in character—all that would amuse and give comfort.” They reached back to contacts in the United States to send such items, and Mamie donated one of her home’s many rooms to house books and supplies that people sent for the men. Mamie noted once to a journalist who took interest in her work that, “These attentions were better than tonics … as the physical condition was soon improved.”

Mamie placed special emphasis on relieving the soldiers’ homesickness, which she diagnosed as a primary cause of their unhappiness. During their visits, Aid Society members carried notebooks to jot down things that soldiers mentioned would bring them comfort. As Mamie noted to the same journalist, “The ladies who minister to the suffering observed that recoveries were slow; that the men seemed depressed and that they grew listless and indifferent. A careful study of this feature convinced us that homesickness was the basis for this condition.” Mamie noted. “The human heart is the same the world over,” she went on, “and when it feels neglected the suffering, whether real or imagined, is increased.” Her insightful compassion, combined with her close-hand experience of the war, helped her further connect the dots to discern the homesickness’s roots as “the great distance from home and the length of time for mails to be received.” She went on to vividly explain, “no matter how scientifically war is conducted and … how well planned the campaigns may be, the horrors that follow the roar of musketry and the shriek of shell are present when the smoke of battle has lifted and the cots in the hospitals are filled with the maimed, bleeding and badly shattered sons of American mothers.” She continued her work with the wounded soldiers even after her return to the United States, remaining vocal in calling for improved methods to support those still fighting and recovering in hospitals.

Despite finding pleasure in her new environment, Mamie remained mindful of the violent conflict that had brought them to the Philippines in the first place. Once she wrote to a friend that she could hear weapons firing where fighting was taking place outside the city, just three miles from the home. “We could hear firing very distinctly for some time,” she noted, “and there has been a little more this morning. As all the ambulances … with sick and wounded, pass right by us we feel that the firing means something indeed.”

Mamie closely followed her husband’s work as his troops strove to drive out the Spanish forces, conducting some of the conflict’s most significant early military engagements. Mamie requested an Army map to track his movements around the interior of Luzon, the Philippine archipelago’s largest island, as Henry led campaigns to capture Santa Cruz, conducted an attack on San Rafael, and captured San Isidro. Once, Mamie and the children drove out to an army encampment on Manila’s outskirts to watch her husband and his troops preparing for such an expedition. She recounted the experience to a friend with her characteristic optimism. The camp, she wrote, was “beautifully situated in a mango grove with coconuts, palms and bananas all around.” She observed that the soldiers were “an interesting as well as a pretty sight, so many men going into camp, settling as systematically as clockwork. They were, to a man, cheerful, brave and ready.”

When Henry’s work earned him promotion to General in June, 1899, Mamie was ecstatic and wrote to friends celebrating his new title, “General Lawton—isn’t it glorious?” That same month, he was placed in command of the U.S. forces defending Manila. On at least one occasion Mamie accompanied him and other officers to observe a nearby battle, with their then-eleven year old son, Manley in tow. Together they sat “coolly in an unprotected boat close to the shore during the fighting, with the bullets splashing about,” she recounted to a friend. This firsthand awareness of the conflict allowed her to develop nuanced opinions on the situation’s complications and the outlook for peace. “I find a solution of the Philippines a very difficult question,” she wrote to a friend, using metaphor to touch on the question of the United States’ involvement. “We can not eat them [the Philippines], nor throw them in the alley when no one is looking.”

When she wasn’t directly supporting her husband, Mamie, as always, was finding ways to strengthen the community fabric that surrounded her. This time, her primary focus became the American soldiers who served with her husband and to whose work she felt intimately connected—for reasons beyond family ties. The military hospital was located a block from her “palace,” and as she observed in a letter to a friend, “the cascoes [sic] bearing the wounded, sick and dead go directly by my door …” During her visits to the hospital, she continued, “it makes my heart ache, but gives me a lesson in patience, cheerfulness, endurance and unselfishness.” It was a perspective that showed the stamp of her grandfather’s legacy, as did her decision to undertake missionary work to improve the recovering soldiers’ situations in the only way that was within her control—by visiting them to offer comforting messages and moral support. Mamie and another officer’s wife organized the “Manila Aid Society” to undertake this mission. The Aid Society began with less than twenty members who met in Mamie’s home, and quickly expanded until they had enough manpower to sustain daily visits to each of the approximately 2,500 sick and wounded soldiers in and around Manila. Members organized themselves into “visiting committees,” selected reading materials for the soldiers that would be “cheering and light in character—all that would amuse and give comfort.” They reached back to contacts in the United States to send such items, and Mamie donated one of her home’s many rooms to house books and supplies that people sent for the men. Mamie noted once to a journalist who took interest in her work that, “These attentions were better than tonics … as the physical condition was soon improved.”

Mamie placed special emphasis on relieving the soldiers’ homesickness, which she diagnosed as a primary cause of their unhappiness. During their visits, Aid Society members carried notebooks to jot down things that soldiers mentioned would bring them comfort. As Mamie noted to the same journalist, “The ladies who minister to the suffering observed that recoveries were slow; that the men seemed depressed and that they grew listless and indifferent. A careful study of this feature convinced us that homesickness was the basis for this condition.” Mamie noted. “The human heart is the same the world over,” she went on, “and when it feels neglected the suffering, whether real or imagined, is increased.” Her insightful compassion, combined with her close-hand experience of the war, helped her further connect the dots to discern the homesickness’s roots as “the great distance from home and the length of time for mails to be received.” She went on to vividly explain, “no matter how scientifically war is conducted and … how well planned the campaigns may be, the horrors that follow the roar of musketry and the shriek of shell are present when the smoke of battle has lifted and the cots in the hospitals are filled with the maimed, bleeding and badly shattered sons of American mothers.” She continued her work with the wounded soldiers even after her return to the United States, remaining vocal in calling for improved methods to support those still fighting and recovering in hospitals.

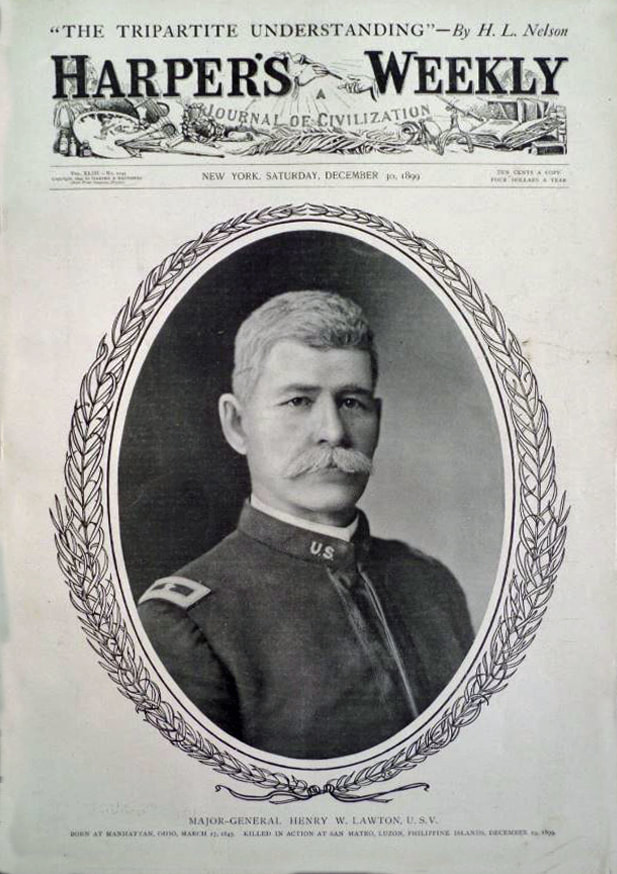

Henry Lawton’s Death

By December, 1899, Mamie was so engrossed in her work and so comfortable in Manila that the shock of tragedy must have taken her totally by surprise. Her family in Pewee Valley received a letter from her in mid-December in which she expressed contentment and spoke of her new home and the life she and her family had built since their arrival nine months before. The pace of Henry’s work had remained frenetic throughout the year, and on December 18 he set out to confront a group of insurgents in San Mateo, a small town to Manila’s northeast. It was an expedition just like so many he had conducted before, and which Mamie had witnessed, but this time he did not return.

While overseeing a battle that rainy morning, pacing back and forth just behind the firing line, Henry was struck by a sharpshooter’s bullet that pierced his lung and ended his life. It was a shocking loss, as high-ranking officers rarely died in battle. A sergeant and several soldiers returned to Manila that evening with news of Henry’s death.

Mamie received the crushing report with as much grit as she could muster. A friend of the Lawton family in Manila wrote that “Mrs. Lawton shows wonderful fortitude and heroism, and her unselfish aim is to spare all around her sorrow and trouble…” Given Henry’s near celebrity status by that time, news of his death made headlines in papers in Manila and across the United States. As they heard the news, members of the extended community network Mamie had joyfully created throughout her life became a safety net in this moment of sorrow. In Manila, she leaned on the military and expat community of friends she had fostered in their short time there, and even received visits from families from towns that Henry and his troops had liberated. Despite their physical distance, Mamie’s extended family in Pewee Valley and Louisville felt every ounce of Mamie’s pain and became a source of emotional support from afar. “Mrs. Craig, the mother of Mrs. Lawton, was quickly notified of Gen. Lawton’s death yesterday morning, and she is prostrated,” one press report noted. “The killing of Gen. Lawton is all the more sad to Mrs. Lawton’s relatives because she is so far away, and they are unable to be with her in her bereavement…they know the devotion which she bore for her husband and realize how much she must have been shocked by the report of his death.” The same article went on, “Mr. Merton Craig was deeply affected when seen by a Courier-Journal reporter yesterday afternoon.” Merton told reporter that, “In such trouble she [Mamie] would naturally look to us at home for sympathy.”

While overseeing a battle that rainy morning, pacing back and forth just behind the firing line, Henry was struck by a sharpshooter’s bullet that pierced his lung and ended his life. It was a shocking loss, as high-ranking officers rarely died in battle. A sergeant and several soldiers returned to Manila that evening with news of Henry’s death.

Mamie received the crushing report with as much grit as she could muster. A friend of the Lawton family in Manila wrote that “Mrs. Lawton shows wonderful fortitude and heroism, and her unselfish aim is to spare all around her sorrow and trouble…” Given Henry’s near celebrity status by that time, news of his death made headlines in papers in Manila and across the United States. As they heard the news, members of the extended community network Mamie had joyfully created throughout her life became a safety net in this moment of sorrow. In Manila, she leaned on the military and expat community of friends she had fostered in their short time there, and even received visits from families from towns that Henry and his troops had liberated. Despite their physical distance, Mamie’s extended family in Pewee Valley and Louisville felt every ounce of Mamie’s pain and became a source of emotional support from afar. “Mrs. Craig, the mother of Mrs. Lawton, was quickly notified of Gen. Lawton’s death yesterday morning, and she is prostrated,” one press report noted. “The killing of Gen. Lawton is all the more sad to Mrs. Lawton’s relatives because she is so far away, and they are unable to be with her in her bereavement…they know the devotion which she bore for her husband and realize how much she must have been shocked by the report of his death.” The same article went on, “Mr. Merton Craig was deeply affected when seen by a Courier-Journal reporter yesterday afternoon.” Merton told reporter that, “In such trouble she [Mamie] would naturally look to us at home for sympathy.”

Henry’s death swept his widow and children into a tide of elaborate funeral events that lasted for months. Other than an initial, private ceremony in the Lawtons’ home on December 22, each subsequent event was an enormous public affair. An elaborate ceremony took place in Manila on December 30 as Henry’s body was transferred from a local cemetery to board an Army transport ship, the “Thomas,” for its return to the United States. Mamie and the children followed his casket through the streets of Manila as a U.S. regimental band played and the all the top-ranking U.S. military leaders in the Philippines, foreign diplomatic officials, members of the Philippine Supreme court, two cavalry troops, a battery of artillery, and a naval battalion trailed behind. As the Thomas bobbed across the Pacific, passing ships lowered their flags out of respect when it came into view.

When they docked in San Francisco a month later on January 30, 1900, Mamie’s family was waiting. They had traveled all the way from Pewee Valley to meet the arriving vessel, and Mamie’s emotion and relief in the presence of her mother and sisters must have been enormous. After a brief stay with friends in that city, the somber party boarded a four-car funeral train on February second bound for Washington, D.C. by way of stops in Indianapolis—where Henry’s body lay in state at the state capitol—and in his hometown of Ft. Wayne, Indiana on February 5. In that town, ceremonial cannon fire and bands playing funeral dirges greeted Lawton’s arriving train. Thousands of mourners lined his casket’s route from the train station to the city courthouse, where a memorial ceremony was held. Henry was finally laid to rest in Arlington Cemetery.

Had the circumstances been more pleasant, the fuss and ceremony of each occasion might have delighted Mamie, surpassing even her own high standards for festive gatherings. She probably managed to find some solace in the friends and relatives who would have flocked to meet the traveling funeral party in each city. The torrents of praise for her late husband she would have read in newspapers and personal letters might have filled her with bittersweet pride. Nonetheless, wave after wave of ceremonial farewells dragged Mamie first out of the brief existence she had built in Manila, then out of the world of her husband’s career in the Army, leaving her adrift to begin to build a new life without Henry, but on her own terms.

Returning Home to Pewee Valley

Mamie launched a flourishing social life centered around her children—particularly her three daughters—and their friends and acquaintances. Local press articles detail Mamie and her daughters’ visits to friends and their propensity for hosting parties and debutante balls with all the usual trappings. In addition to picking up old ties, she made new acquaintances. The most notable among them was Annie Fellows Johnson, a neighbor and aspiring writer who based the characters for her popular novels on Mamie and her extended family. The friendship that flourished between the two women lasted for the rest of their lives.

The family’s new social fabric also included threads from Henry’s time in the Army, and the military world left a lasting impact on Mamie and all her children. Her son, Manley, joined the Artillery Battalion Kentucky State Guards, where his uncle Merton Craig had served as a member, Commander, and later as paymaster. Mamie hosted visits from old Army friends and colleagues and enthusiastically participated in engagements such as a Spanish American War Veterans’ Reunion in Indianapolis, taking the lead on the social engagements by arranging a reception for the Ladies’ Auxiliary. As evidence of the close ties she kept with friends and colleagues who remained in the Philippines, when Mamie’s friend, the wife of Dean Worcester, Secretary of the Interior of the Philippines, requested her help in organizing “a proper American Christmas” for local children in 1902, Mamie leapt at the task and gathered and packed up all the trappings of a portable Christmas to ship to Manila, including a real Christmas tree, candles, popcorn for making popcorn chains, and “all means of knick-knacks.” She also carried on the work she began with the Hospital Aid Society by advocating publicly for greater support to wounded and recovering soldiers.

In 1907, the opportunity to attend the dedication of a statue of Henry Lawton in Indianapolis was a testament to all that Mamie and Henry had gained from his time in the Army. Rather than wallow in grief over the reminder of her beloved husband’s sudden death nine years prior, Mamie delighted in the event for all its festive details and the chance it offered to see old army friends. As she and family prepared to attend the dedication, she was thrilled to see old friends and tickled by all the ceremonial trappings, writing to one close friend of her joy in seeing people she and Lawton had been with over the course of his career. “I was in a giddy whirl,” she wrote to a friend. “Other friends, more flowers, people I never met before, reporters, old soldiers, Henry’s old comrades, members of the Monument Commission, etc., etc., etc. The next day was full to the brim. Henry’s old regiment came in detachments, and some were very pathetic. I can’t tell you how beautiful everything was.”

The family’s new social fabric also included threads from Henry’s time in the Army, and the military world left a lasting impact on Mamie and all her children. Her son, Manley, joined the Artillery Battalion Kentucky State Guards, where his uncle Merton Craig had served as a member, Commander, and later as paymaster. Mamie hosted visits from old Army friends and colleagues and enthusiastically participated in engagements such as a Spanish American War Veterans’ Reunion in Indianapolis, taking the lead on the social engagements by arranging a reception for the Ladies’ Auxiliary. As evidence of the close ties she kept with friends and colleagues who remained in the Philippines, when Mamie’s friend, the wife of Dean Worcester, Secretary of the Interior of the Philippines, requested her help in organizing “a proper American Christmas” for local children in 1902, Mamie leapt at the task and gathered and packed up all the trappings of a portable Christmas to ship to Manila, including a real Christmas tree, candles, popcorn for making popcorn chains, and “all means of knick-knacks.” She also carried on the work she began with the Hospital Aid Society by advocating publicly for greater support to wounded and recovering soldiers.

In 1907, the opportunity to attend the dedication of a statue of Henry Lawton in Indianapolis was a testament to all that Mamie and Henry had gained from his time in the Army. Rather than wallow in grief over the reminder of her beloved husband’s sudden death nine years prior, Mamie delighted in the event for all its festive details and the chance it offered to see old army friends. As she and family prepared to attend the dedication, she was thrilled to see old friends and tickled by all the ceremonial trappings, writing to one close friend of her joy in seeing people she and Lawton had been with over the course of his career. “I was in a giddy whirl,” she wrote to a friend. “Other friends, more flowers, people I never met before, reporters, old soldiers, Henry’s old comrades, members of the Monument Commission, etc., etc., etc. The next day was full to the brim. Henry’s old regiment came in detachments, and some were very pathetic. I can’t tell you how beautiful everything was.”

Conclusion:

It wasn’t until Mamie’s children left the nest that she considered departing Pewee Valley for good. Manley, who decided to pursue a military career in his own right, was the first to leave. With his father’s military colleagues lobbying on his behalf, he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to become a cadet at West Point in 1905. He later served in World War I but was medically discharged due to injuries suffered in a gas attack. He eventually settled in Washington, D.C. where he married and had two daughters. Mamie’s daughters moved to Annapolis, where two of them met and married Naval Academy cadets.

In 1912, Mamie moved to Annapolis herself to be closer to her children and their growing families. She sold The Beeches to Annie Fellows Johnson, noting in a letter to Johnson the comfort it gave her to know a friend was inhabiting the home that was so special to her. She lived the rest of her life in Annapolis enjoying family visits, during which one granddaughter remembers her as an elegant and formal grandmother, always in white, bending over to kiss her young grandchildren on each cheek. Mamie died in 1933 and is buried alongside her husband in Arlington Cemetery.